This is Who We Are: Professor Adama Delphine Fawundu '18

This Is Who We Are is a series featuring Columbia School of the Arts’ professors, covering careers, pedagogy, and art-making during a pandemic. Here, we talk with Assistant Professor of Visual Arts, Director of Graduate Studies, and alumna Adama Delphine Fawundu '18 about getting her start in the golden era of hip-hop, studying for an MFA at Columbia University and finding her voice as a visual artist.

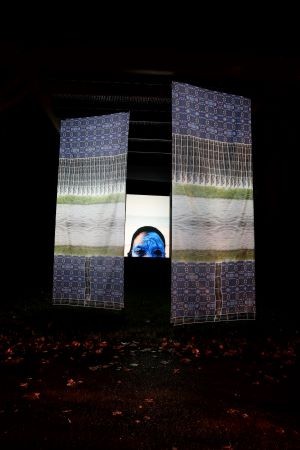

Assistant Professor Adama Delphine Fawundu was finalising a new outdoor project with Clea Rsky (pronounced ‘Clear Sky’) when we spoke. The experimental arts initiative approached Fawundu to install something in Crown Heights, her Brooklyn neighbourhood earlier this year. “I was really wracking my brain because I knew I didn’t want to just present some photographs of the neighbourhood,” Fawundu said. As an artist, Fawundu is known for her multimedia works: textiles combined with photographs and found objects to surprising and provoking effect. This is thanks to an art process that places trust in intuition and association over concrete plans. For the Clea Rsky project, Fawundu told me over Zoom, “It came to me to use cyanotype and I thought about the idea of the project being outside and being exposed to the sun but also the idea of memory and how memories are constantly changing and fading, so I wanted something that would change with the environment as the neighbourhood is completely changing and then this idea came to me yesterday: it’s a scroll.” She is documenting the installation, which runs until January 2022, on her Instagram account.

Fawundu cut her teeth as an artist documenting New York’s hip-hop scene back in the 1990s. “To me hip hop was more than music: it was a culture. This expansive thing that was extending into the community,” Fawundu said. Born and raised in Brooklyn, the epicentre of the music phenomenon, Fawundu wanted to capture this epoch through ambitious feature length documentaries; but on trips to the Library of Congress to flip through the photo books of greats like Chester Higgins, Roy DeCaravas, Mary Ellen and Diane Arbus, she was moved by what the photographs captured. “I realised you could tell stories with photos. You didn’t need to do this whole big documentary. I could focus on small stories and extend them, continuing them over many years.” She took to the streets, photographing artists in their communities. Soon, she was hired by magazines like The Source and Vibe; this went on until the early 2000s when the music industry started to change. “It got more commercial,” she said. “So instead of doing a photoshoot in the Queensbridge Projects with Mobb Deep it became some high-end studio with make-up and hair and I was like,” Fawundu waved her hands in the air, “I’m not interested in this anymore.” While the music industry commodified the culture she grew up in, Fawundu set her sights further afield.

“I found a grant to go to Ghana and spent the summer photographing musicians there.” She saw the influence that hip-hop had on the new sounds these musicians were creating. The most striking aspect of this discovery was the way the musicians' own heritage informed their work. Born to parents from Sierra Leone and Equatorial Guinea, Fawundu had always wanted to incorporate her heritage in her own work. What she heard in the sounds of the Ghanian musicians she documented was an isomorphism between the Diaspora (represented, in this case, by New York hip-hop) and African culture. “I found this really beautiful, as though it was coming full circle.” So Fawundu started travelling to more cities and more countries across the African continent. At the same time, she began to turn the camera on herself.

“I never consider any of the photos of me to be entirely self-portraits,” she told me. Instead, she uses her body symbolically––a part to represent the whole. Her first step into the conceptual realm was back in 2012. In Deconstructing SHE, Fawundu used the song “Four Women,” by singer-songwriter Nina Simone, as a lens through which to examine the theory of social constructivism in the development of identity, styling herself as the strikingly different personas of “Aunt Sara,” “Safronia,” “Sweet Thing,” and “Peaches.” Laughing, Fawundu said, “I remember exactly when I took those photos: it was the day of Hurricane Sandy. I had the studio setup, I had hired a make-up artist and she left just before the hurricane started. If she hadn't left she would have been stuck with me. I didn’t want that! I said, ‘You know what, I think you should go home.’”

Starting out as a blog, Deconstructing SHE grew into an exhibition. At the same time, Fawundu was still exhibiting her music work. But it wasn’t enough. “I started to get interested in screen printing and textiles. It was all a bit of a blur and I kind of felt like I needed some guidance.” That’s when Fawundu decided to return to school.

What complicates Fawundu's story as an artist is that throughout this fertile period of creative growth and experimentation she was also a mother of three children and holding down a full-time job in education. “I never considered my photography to ever be a part-time thing. It was always: go hard photography; go hard teaching; go hard mum.” She applied for MFA programs in 2015, and the following year was accepted into the Visual Arts MFA Program at Columbia University School of the Arts, the only school she applied to. “Columbia made sense because it was interdisciplinary. Some of the other schools in New York were so photograph-focused and I knew that I wanted to play around. I wanted critical feedback and to research and to do all those things,” Fawundu said.

“I tell you one thing, it was a scary thing, that first week of school. Here I am: I’m no spring chicken, I have three children. One of them was in college, another about to graduate high school. Life was happening and here I am quitting my full-time job to go to school full-time and I said: ‘What did I just do?’” Despite her fear though, Fawundu's time at Columbia led to a turning point in her artistic practice. “I had this table set up in my studio and I brought all these things from home that inspired me: there were the pictures of my grandmother, these bundu masks that I had from Sierra Leone, fabric that my grandmother had hand-dyed, pictures of my mom and dad, a whole lot of beads. I knew I wanted to go deeper into Mende culture in particular because I am named after my paternal grandmother and I had enough information about her. So it was kind of like being in communication with her spiritually because she’s no longer here.” Columbia also gave Fawundu the space to reconfigure her artistic vision by digging deeper into Mende ontology. “I realised that what interested me inside the United States were these hybrids of culture. The language of hip-hop, for example, is very similar to the language of creole and the syntax of indigenous African languages: the double negatives, the figurative language. If you listen to my mom speak, everything she says is figurative. Those were the synergies I found myself interested in.” Afterwards, Fawundu started making work that was interested in patterns and layers and the nuances of history and how we are conditioned to perceive them. To this, her Artist’s Statement is telling. It reads in part:

Unfolding layers only to create new ones.

Despite the interruptions, disruptions, interjections, and attempts at erasure --

Our strength is in the syncopation.

“Change,” as she writes for her project with Clea Rsky, “is constant.” But just as much as Fawundu’s work is about expressing this change, so has it become about preservation; particularly as it relates to the Afrodiaspora. With her friend, the documentary photographer, Laylah Amatullah Barrayn, Fawundu co-founded MFON: Women Photographers of the African Diaspora in 2017, a commemorative publication of work by over a 100 women and non-binary photographers of African descent. The publication was inspired by Jeanne Moutoussamy-Ashe’s Viewfinder, a similarly conceived photography book. Only Viewfinder was twenty years old and, as Fawundu tells me, “there were no other books like it.” Fawundu and Barrayn proceeded to research MFON over a thirteen year period. They didn’t want to go through publishing houses. “There was something with this gatekeeping culture that meant it could be stressful to explain to someone the value of this project. We didn’t feel like we needed to wait for someone to say we could do this.” So MFON was self-published while Fawundu was still a student at Columbia. “It was actually amazing how well it did,” she said. “We had one write up in the New York Times and then from there it just took up a life of its own. People were contacting us from Vogue and the BBC. This was right when I’m doing my thesis in graduate school.” Today, MFON is in library collections around the world and many photographers featured have experienced success as a result. Fawundu and Barrayn are in the early stages of archiving the project, to preserve this important work before, once more, the landscape changes entirely. As Fawundu tells us, “our strength is in the syncopation.”

Adama Delphine Fawundu is a visual artist born in Brooklyn to parents from Sierra Leone and Equatorial Guinea, West Africa. She has presented public installations at Prospect Park in Brooklyn and Federal Hall in New York City. Solo show exhibitions and performances include Art@Bainbridge/Princeton University, The Penumbra Foundation, the Jefferson School African American Heritage Center, The Miller Theater at Columbia University, Wadsworth Atheneum Museum of Art, Museum of the African Diaspora, San Francisco, African American Museum in Philadelphia and Granary Arts amongst others. Her works can be found in the collections at the Brooklyn Museum of Art, Princeton University Museum, Bryn Mawr College, The Brooklyn Historical Society, The Norton Museum of Art, The David C. Driskell Center (University of Maryland), The Petrucci Family Foundation, The Museum of Contemporary Art at the University of São Paulo, Brazil, as well as private collections. Projects have been supported by Rema Hort Mann Artist Grant as well as the New York Foundation for the Arts Fellowship amongst other awards. She was featured in the critically acclaimed Netflix documentary, In Our Mother’s Garden, directed by Shantrelle P. Lewis. Fawundu joins Columbia University School of the Arts as an Assistant Professor of Visual Arts and the Director of Graduate Studies.