Theatre in Motion: International Dramaturgical Consulting with Anne Hamilton ’94

In Theatre in Motion, we discuss theatre's movement across stages, through time, and within communities with its creators and practitioners.

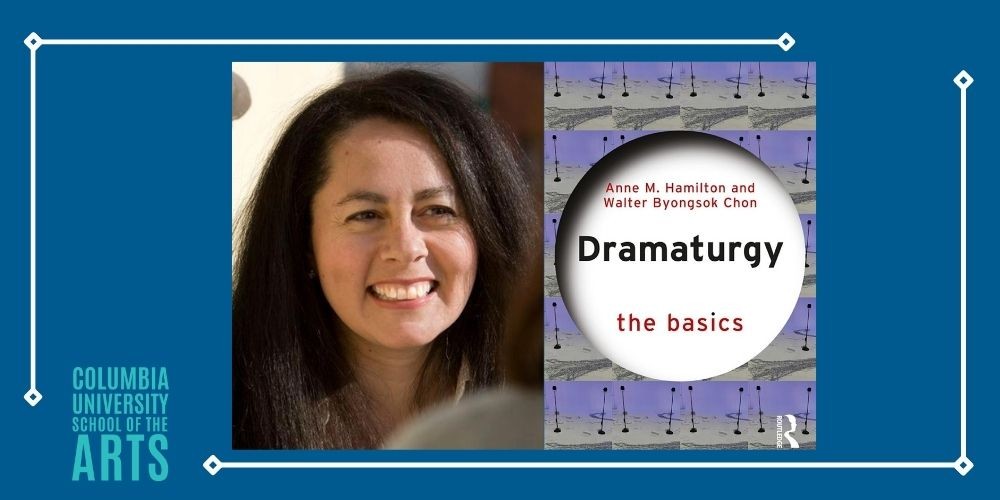

We talked about defining the practice of dramaturgy and dramaturgical consulting around the world with Dramaturgy alumna Anne Hamilton ’94.

Anne Hamilton is the founder of Hamilton Dramaturgy, an international dramaturgical consulting company. She has spent 32 years working across the globe as a freelance dramaturg. Hamilton’s specialty lies in script development of new plays, musicals, screenplays, TV pilots, nonfiction work, novels, and memoirs. She has worked as a consultant for Associate Professor Lynn Nottage, director Andrei Serban, the Public Theater, The Directors Company/The Harold Prince Musical Theatre Institute, Tony Award-winning director Michael Mayer, Classic Stage Company, Jean Cocteau Repertory Theater, playwright Leslie Lee, the New York City Public Library’s Schomberg Center for Research in Black Culture, and the University of Iowa Playwrights’ Workshop. Hamilton was awarded a fellowship in recognition of her contributions to the American theatre by the Bogliasco Foundation of New York City and Bogliasco, Italy. Her book, Dramaturgy: The Basics, which she co-authored with Walter Byongsok Chon, was published by Routledge in late 2022.

Can you tell me about your personal theatre history?

Anne Hamilton: I grew up in New Jersey, so I was right across the river from Manhattan. And I always wanted to get there. I sang a lot when I was a kid and a teen. And then I also did a lot of singing, a little bit of movement, and a lot of onstage work in my twenties. At the same time, I was a writer and I worked in publications and public relations. I was an English Literature major in undergrad, so writing was always a part of my life—really a part of my core. After earning my degree, I decided that I wanted to try to become a theatre critic, so I sought training at the Master’s level. There were only four Master’s degree programs in the country at the time that focused on dramatic criticism. So I applied, I got into Columbia right away, I moved, and I just kept going. I’d say that the practice of theatre has always been a very, very clear part of my core.

In theatre today, dramaturgy has a fairly fluid definition. Can you tell me how you personally define dramaturgy?

AH: I define dramaturgy as the practice of being a literary, historical, and artistic consultant. I try to use the training that I received at Columbia, as well as all the other things that I've done in my life. I bring information and experience to bear in assisting the person who hires me, or that I've been brought in to assist. It's kind of like holding a safe space open for the artist(s) that I'm working with, whether it's a playwright, a director, an ensemble, or something like that.

How did you transition from wanting to be a theatre critic into focusing on dramaturgy? What prompted that pivot?

AH: When I got to Columbia, I fell in love with dramaturgy. I found that back then in the early nineties, before technology united us all on a similar or accessible platform, theatre criticism was not able to give me experiential access to making theatre. It was clear to me that if I were to become a theatre critic, I would not have behind the scenes or behind the curtain experiences. And I didn't want to lose those things. I felt more comfortable, I felt more inspired, I felt destined to keep working as an artist because that's what I really wanted: I wanted to expand my artistry and my production of theatre. My production of theatre—especially because I had been on stage for years and years in New York City, and previously in New Jersey.

That is not to say that theatre critics aren't artists. They certainly are. At the time, the training at Columbia trained us for both applications: dramaturgy and dramatic criticism. I just felt that the application of the training and the knowledge that I was gaining and the ways that I was growing would be more suitable to a path that collaborated and actually put shows on. So that's how that happened to me; it was a surprise.

What inspired you to found Hamilton Dramaturgy?

AH: Well, at the time that I went to grad school in 1991, the American Regional Theatre Movement was just a few decades old. There were very few jobs for literary managers and dramaturgs—it felt like there were maybe a dozen serious, stable jobs available. And the individuals in those positions, understandably, were staying in their jobs. There wasn't a lot of turnover. So I looked to my future and I thought: okay, I need to make a living for myself, so what am I going to do? The impetus for the formation of Hamilton Dramaturgy happened in my first year at Columbia: the playwright Leslie Lee, who wrote, among other things, The First Breeze of Summer, was teaching at the Frederick Douglass Center for the Creative Arts on 96th Street. He contacted Columbia and asked for a recommendation of someone who could teach an advanced playwriting class with him. I was recommended for the position, and I met him and I got along with him. I began co-teaching this advanced playwriting class with him, which I did for two or three years. And I started to get consulting experience outside of the university right away, because the class we taught also included a literary play reading series. From my position at the Frederick Douglass Center, I eventually served as the literary manager of a new play reading series at the Schomburg Center for Research in Black culture.

Essentially, I was doing the work of consulting with people outside the university. I just started charging for it, and the consulting business grew from there. I think that when you're lucky enough to be in New York City, and you're lucky enough to be in grad school at Columbia, you can get on the subway and go downtown and not only see shows, but network with hundreds and hundreds of playwrights and artists around you. You find opportunities. I felt confident in the training I was receiving at Columbia and I felt confident in my abilities as a literary specialist—because that's what, to me, a dramaturg is: a literary and theatrical performance specialist.

While I was taking on private clients, Leslie Lee was teaching a course in NYU’s Dramatic Writing program. I would sometimes give a lecture in his class about dramaturgy, and then people would want to hire me. I was lucky to get clients from within academia, and from those who were active in the industry outside of academia. And it helped that I wasn't really a stranger to business, because in my twenties I had worked in businesses. I had been an office manager for an architect in his private studio practice, and I had worked in writing, editing, publications, and public relations. I had a business side, which I knew how to employ, and I wasn't scared of that. But it's hard to start a business. Hamilton Dramaturgy was one of the first sole proprietorships in the country that was modeled after a professional practice, similar to that of an architect, physician, attorney, or engineer. Because of that, it couldn’t initially sustain me as my only job. So I worked other full-time jobs in the city for the next couple of decades. I would spend my days working a full-time job and then I would do my dramaturgical consulting on nights and weekends, year-round. That dedication was how I built the practice.

How did you expand Hamilton Dramaturgy internationally?

AH: Columbia is such an international school that I felt confident working with people from other countries. And I’m also half Italian—my mother was an Italian citizen when I was born. I have a family over in Italy. I had traveled abroad, so it just seemed natural to me to make myself available not only in the fabulous New York City theatre scene, but across the world. It just made sense; that's what businesses do, right? That's what talented, skilled individuals do. They offer their services. The way I built the company was by staying up to date on the forefront of technology—which has certainly changed considerably in the last three decades. For instance, when email was created, I invented a newsletter called ScriptForward! for which I commissioned articles by translators, professors, and playwrights around the world. All by email, I created this network. So not only did I get referrals by word of mouth, but I actively created informative marketing materials to try to help other people out that were new or newer to the field, and also to let people in other disciplines know what was going on in dramaturgy that could possibly be useful to them.

I maintain the business from here in the US, so I work online with people worldwide. It’s very easy to stay connected, and I find that the company’s development has mirrored the way that theatre companies expand: you do your programming and you build your bridges with other artists and you try to create something. It just so happens that Hamilton Dramaturgy is not a presenting organization, so I don't need to bring anyone over to work with them here, and I don't need to physically travel to other countries. I've so easily worked with people in England, Australia, Ireland, and Italy, all because of the technology available to us.

You recently co-authored a book called Dramaturgy: The Basics with Walter Byongsok Chon. What was it like to condense the practice of dramaturgy down to “the basics?”

AH: It was a really wonderful process. Together, my co-author and I have fifty years of experience in a wide range of educational institutions, venues, and locations. I have developed syllabi and introduced the subject at various colleges throughout the years. Walter Byongsok Chon is an Associate Professor at Ithaca College. He was charged with creating the dramaturgy program at Ithaca College—developing the classes and determining the function of dramaturgy within the school’s Theatre program. He has been teaching dramaturgy from script analysis through advanced dramaturgy for six years. While I have done shorter, single semester visiting professorships and lectureships, Walter is particularly conversant in teaching dramaturgy because it’s something that he does every day.

When we received the invitation from Routledge to write a proposal for The Basics series, we wrote the proposal together. Then we divided the tasks according to what was best and most efficient for each person to do at the time. Because we had developed different specializations throughout the years in each of our dramaturgical practices, we together had a complete understanding of the research materials and knowledge important for dramaturgy’s “basics.”

We each drew upon personal knowledge and experience to write the content. It is a short book—only 60,000 words. So we had to be really effective and think about how to present material to students ages 14–24. It's a global textbook for high school and college students, and anyone else who wants to learn, of course, because it's packed with examples. What we did was think deeply about how we could present this material to students using effective diction and the right learning units. Walter and I decided upon the key subjects together and then created and edited the manuscript.

What excites you or moves you in theatre, as a maker and as an audience member?

AH: I always watch how people are inventing and executing various forms of theatre—how they're pushing the form and the presentation of the story in different ways. The addition of projections, the advancement of sound design, and multimedia pieces interest me. Also, I'm interested in how different playwrights’ careers develop; I am a dramaturg in the present, but I like to look at things from a historical perspective, so I like to follow how one playwright’s career is developing, what direction they're heading in, and what their oeuvre looks like. I try to look at the whole theatre landscape to see what different artists are contributing and how that's really changing that landscape. I really love the individual work with a person—with the playwright, the director, or the representative of a theatre company—and the work of writing my own plays. But I also love to take an overview. As an English Literature major, I was trained to look at different periods in literature to discover what their hallmarks were, and that skill is still with me in my work in theatre. I like to look at it from the inside and the outside.