Soundable Depths: The Magnificent Art of Listening Underwater

I was surrounded by sounds so otherworldly, I felt like I was listening to the stars talking.

Thousands of tiny scintillant shivers, small clicks and rustlings like glass crickets, tiny shatters, a swell of shimmer. Is that what a school of fish sounds like? There was no way to tell. I was left to my imagination; trying to identify, but then only dreaming, listening, immersed in the story washing all around me.

This is The Art of Listening: Under Water, the site-specific spatial audio installation newly opened at the Lenfest Center for the Arts, on display from February 3-13, 2022. It is the creation of Norwegian artist Jana Winderen, in collaboration with Tony Myatt.

Visitors experience a composition of underwater recordings Winderen has made around the world since 2005, in bodies of water as varied as the Caribbean, the Barents Sea, and the Hudson River.

Originally presented in a rotunda at Art Basel in Miami Beach, the artists have completely reconfigured the experience for exhibition in The Lantern, the top floor space of the Lenfest Center for the Arts.

The long Lantern space is almost entirely empty but for speakers—speakers on stands at intervals along the walls, and surrounding a cluster of round black ottomans in the center, where listeners can sit or recline. There are also speakers fixed to the gallery’s soaring ceiling, giving the impression of being many fathoms deep.

I sat on an ottoman, facing the southern window, staring at a neutral place on the floor. The scintillant sound receded, and was joined by a dull thumping, like waves against the side of a boat. At other times, the dominant sound was a dry shuffling, scratching and cracking, I imagined crustaceans, snapping, tearing.

Dolphins came, or were they seals? Creatures that sounded like electricity, buzzing and whirring, clicking, whistling, smacking and fuzzing like static.

And then, a droning roar overtook the space, traveling from one corner to another: an engine. The delicate constellations of natural voices were overpowered by jangling beeping, machine signals, and the blaring of a klaxon. It was almost unmistakable—these oppressive sounds were ours; human noise dominating the soundscape.

These rising and falling dynamics, the introduction of new themes and characters, felt both symphonic and narrative.

“I don’t want to make it too literal…I want it to be open enough for you to make your own story," Winderen told me in an interview. The result is an invented space, where the sounds of many biomes exist all at once.

As Myatt puts it, “The Art of Listening: Under Water is not a marine documentary…it provides an artistic, aesthetic experience through its encounter with marine life.”

That aesthetic sensibility is why Winderen does not provide a list of the recorded species in the installation. She doesn’t want visitors to start listening for certain fish, at the expense of hearing the whole. “You lose the ability to lose yourself in the piece,” she said.

She prefers to explore the more educational side of identifying specific sounds in the format of a talk, like the one the artists gave on February 5, 2022.

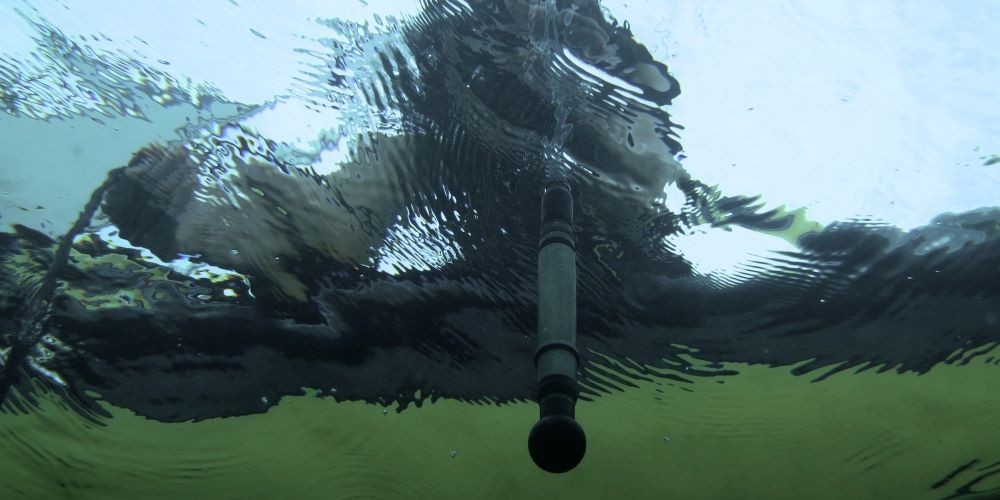

Winderen selected particular sounds to isolate and name—water bugs, melting ice, a pilot whale. She accompanied them with a slideshow of her photographs and drawings, as well as photographs of her process and her audio mixing set up.

In his segment, Myatt discussed how our sense of spatial audio is constructed, and the technology and theory behind the recordings featured in the installation.

“The challenge is to create something that can capture spatial information which is integral to the mixes and balances of sound,” Myatt said, “to produce something that will appeal to our perception in some way."

In a Q&A with Dean Carol Becker on February 5, the artists discussed how they reconstructed the installation for the Lantern.

“A large part of the creation of these works happens in the space,” Myatt said. When Winderen moved the installation from the relatively small space in Miami to the Lenfest Center, “it sounded empty, not very present, not really much of a thing…and then Jana got to work.”

“What are the acoustics of the space, what is the light like, what does it feel like…Working with the space, and not against it,” Winderen told me, is key. “There are also very specific visual decisions made as well.”

The installation in the Lantern uses natural light, its wall of windows covered by blinds to filter out the more distracting visual noise from the city, flattening the image while still allowing the room to feel extended through the windows. It also allows for different experiences with light at different times of the day.

The entrance to the Lantern is around a corner, a sort of decompression corridor, which Winderen says allows visitors to leave the noise of the world behind them: “If you come in straight from outside, you are very hectic…so it’s good to have a transition state. You’re fading out, and fading in.”

This adaptational approach is consistent with Winderen’s practice of recording in the wild. She emphasized the importance of local knowledge, how she relies on locals to discover how or where she might locate certain species, or even techniques for listening.

Interaction between human populations and aquatic biomes, particularly the destructive effects of human activity, has been front of mind for Winderen and Myatt. Part of Winderen’s project has been to capture the sounds of a healthy ocean, as well as the intrusive human sounds that can make it impossible for marine species to communicate, mate, or migrate.

Winderen spoke about recording schools of fish congregating by moonlight in the Chana district in Thailand. The local fish population, slowly built back over decades after being destroyed by commercial overfishing, is now under threat by the construction of a new harbor, “so it will be dead again.”

“I want to have these very lively recordings so people can hear, this is what it can sound like,” Winderen said.

“It is my hope," Myatt said in his talk, “that bringing underwater sound materials to our human experience will support an embodied engagement…to establish an empathy with sound-dependent marine life.”

Immersing visitors in the soundscape of biomes under anthropogenic threat certainly implicates each listener. If only human beings could stop imposing themselves on the natural world, and instead, listen.

“That crackling sound that you hear in the background of a lot of recordings is present in every ocean everywhere in the world,” Myatt noted. “Nobody really knows what it is. You hear all sorts of stories, but nobody actually knows.”

The conventional idea of underwater spaces as silent could not be more demonstrably wrong. A healthy body of water, as Winderen and Myatt so astonishingly and movingly show, is one that is teeming with life, noise, and mystery. It is our responsibility to not drown it out.