Constructing Futures: Making Ecological Art in an Age of Uncertainty with Professor Nicola López

Constructing Futures: Making Ecological Art in a Time of Uncertainty is a series that features artists who use found materials, natural resources, and the landscape to construct work that addresses the harsh realities of our ecological age.

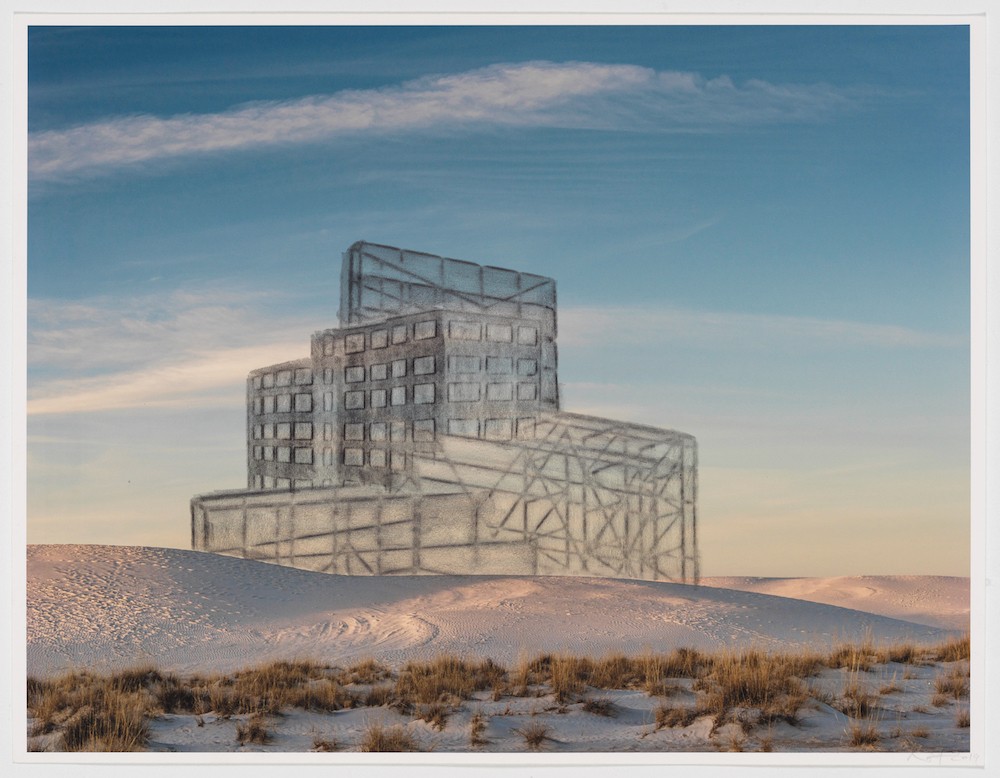

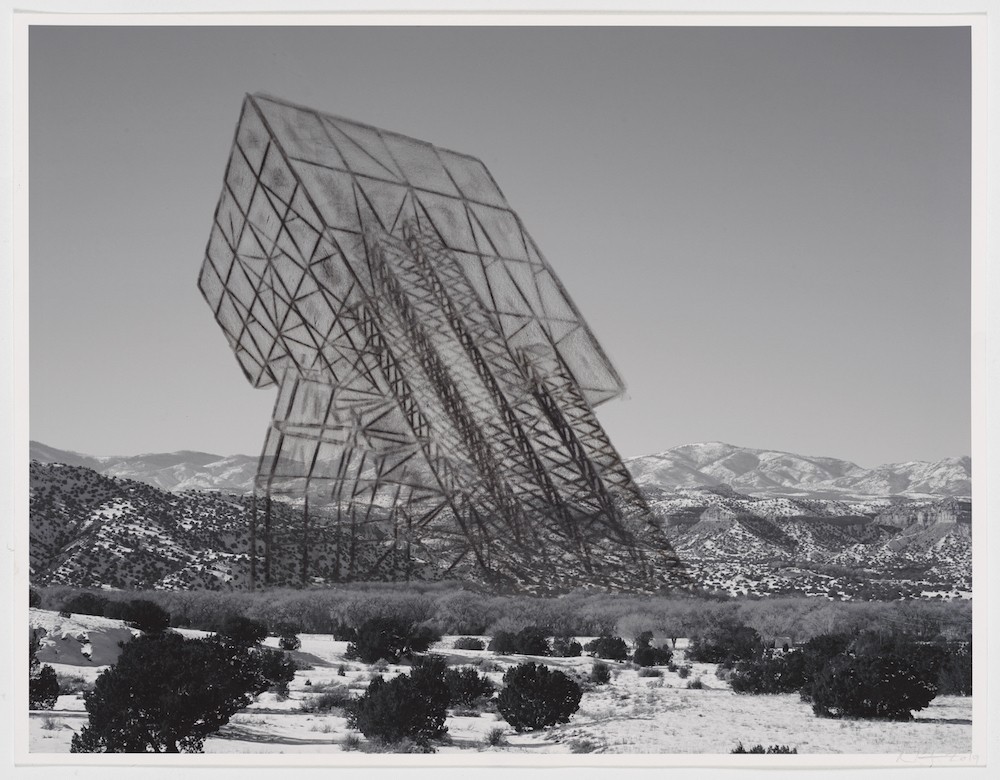

Associate Professor Nicola López works across many disciplines including printmaking, collage, drawing, animation, and sculpture. Her work often revolves around architectural images made strange. This gap between the everyday-ness of our human-built environment and its eerie reconstruction in her work invites the viewer to reconsider their day-to-day environment.

López (b. 1975) received her BA and MFA at Columbia University in 1998 and 2004, respectively. Her work has been exhibited widely both in the United States and internationally at institutions including the Museum of Modern Art, NY; Los Angeles County Museum of Art, CA; Denver Museum of Art; and the Museo Tamayo, Mexico City. López’s work has been the subject of solo exhibitions at the Chazen Museum of Art, Madison, WI and the Solomon R. Guggenheim Museum, NY. She was commissioned to create a temporary site-specific work for The Metropolitan Museum of Art in 2013.

Do you see your work commenting on human made climate change? If so, in what way?

Nicola López [NL]: I would say yes, it is commenting on and exploring it. It's such a complex part of our current reality and of such fundamental importance to our collective and individual futures on every level that it's really hard to stand at any distance and have any sort of detached commentary.

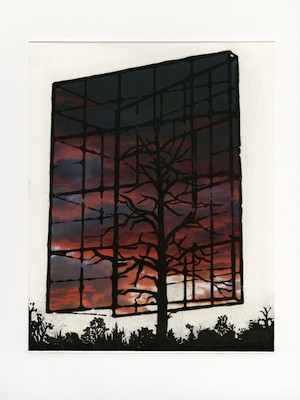

Nicola López, Sunsets and Blue Skies: Storm Brewing, 2018

I feel so embedded in it. I am affected by it emotionally but am also so complicit in it and at times painfully aware of all the ways in which I engage and contribute to climate change. That's a long preamble just to say that any kind of comment I make is also an exploration of my place in it.

My work explores it in different ways. There's work that questions what the future will look like. There's work that envisions that future and wants to expose the real tragedies and short sightedness of our (and I’m aware that I’m using the collective in a really broad way) collective actions and a failure to meet the situation of human induced climate change. So there's work that does point fingers and is something of an indictment, but there's also work that desperately hopes for something different, for positive transformation and for a future that is less precarious.

There’s also work that isn’t overtly about climate change but still engages it in a less direct way. I think that a lot of work made today is necessarily about climate change at least in a tangential way because climate change is an issue that pervades every aspect of our lives. Any work that engages landscape—either what we call ‘nature’ or the ‘built environment’—is about climate change in one way or another. Any conversation about architecture is also a conversation about climate change: about resources, sustainability, \ values and priorities, as well as the way humans relate to both the immediate place/context and also to the larger environment. A lot of my work engages the architectural, the human-built, largely urban environment, and their intersection with the ‘natural’ world. So even the work that's not overtly sending a pointed message about climate change specifically is engaged in that conversation.

I was really struck looking at your work by the lack of human figures. You spoke about our individual complicity and the idea of human induced climate change and so I am curious about this lack of human figures and how it relates to your thinking about our ecological age? How might this lack of human figures be commenting on the climate crisis?

[NL]: There are several reasons for the lack of figures in the work. The minute that there is a human figure our focus goes to that figure and wants to weave a specific narrative that’s happening to that person. In a way, maybe the lack of figures is an effort to move into a larger conversation where it’s not about a specific person or a specific narrative based around individuals, shifting it instead towards a conversation about larger systems of value that have played a huge role in laying the foundations for human-induced climate change.

There are times when I question that lack of overt human appearance because I want to be really careful not to shift the responsibility away from humans. I don’t mean to relinquish responsibility or overlook the complexity of that human responsibility in which some people and parts of society are more responsible than others for the causes of climate change even though the effects will largely be experienced first and most acutely by those least responsible. But I do think that human presence remains very present in my work. It is simply that instead of the human figure I represent the human through construction, built structures, and infrastructure.

Absolutely. It is a tacit or implied inclusion of the human through our structures. You also mentioned how any landscape in 2021 is inherently in dialogue with what is happening in the climate. We have this history of landscape art and I'm wondering how you see that having changed because of our current climate moment. What is the idea of landscape in 2021? How has that idea changed or been threatened by our current environmental reality?

[NL]: I think even the idea of landscape already positions humans in a very specific relationship to land. It basically frames land through the human point of view. This puts the human in a position of power, of dominance, and of centrality. This has been the case throughout the history of landscape art. There are definitely some specific moments in landscape work that have had to do with expansionist and imperialist views. So I think that the whole idea of landscape art is charged with a very complicated history. That’s not to say that every artist who works with landscape is intentionally engaging that history, but I think that it is inherently, even if unconsciously, building on that history.

I think landscape art in 2021 is also about looking at a land that is forever changed. As people speak about the Anthropocene, we are understanding that our world is shaped even at the geological level by human activity on the planet. So in a way, what many people have thought of as a kind of separation between the human viewer and the viewed landscape is getting closer and closer, inseparable. It is now impossible to engage landscape without witnessing human impact on it.

That's so interesting, and I wonder whether the lack of human figures in your work shows just that. It asks the question: What does the human figure add to a landscape that is already so altered by it?

[NL]: Yeah, exactly. I want to add that one way I engage the landscape is as evidence, evidence of human activity. And at this point, that's not just for the architectural, urban landscape, the intentionally human-built landscape, but it also applies to any ‘natural’ landscape which also now inevitably acts as evidence of humanity shaping the planet we live on.

We’ve been talking a bit about time and the history of landscape art and so I'm wondering whether you have a history of visual art you feel your work is in dialog with. And we also talked about certain parts of your practice being constructions or imaginations of the future that contain a hope that feels beyond reach. I'm wondering what those futures look like.

So maybe it's a two part question: First, how is your work in relation to the past, what sort of histories do you feel it's in dialogue with? And second, what kind of future is your work trying to create?

[NL]: I think a lot about visionary architecture, ways that artists and architects have seen buildings and larger building projects as avenues for transforming society, human experience and our collective future. Some of these projects and plans were intended to be put into practice while some of them were hypothetical utopias, impractical and impossible. Many projects would actually have been horrific if they had been built—and some of them were—but the idea of failure in this arena is also something that interests me. Buckminster Fuller, Archigram, Super Studios, and Le Corbusier all worked with these ideas. Even Breugel in the 16th Century when he painted The Tower of Babel was thinking about a vision of another time, maybe a combination of past and future, as represented through architecture.

I’m interested in the idea of time and the connection between history and the future, which I think is really relevant in this whole conversation about climate change. There is an acute awareness of how our past and present are shaping our future, especially as we stand in a place where the future looks so much more fragile and vulnerable than many of us feel it has been before. In some ways, the future is really in focus because it's in question.

Some of my artwork asks what the future will look like or questions the very viability of human existence in the future. I wouldn’t say that my work is ‘aspirational,’ in the sense of depicting a future that I am hoping for—although maybe that is something for me to think about as I do believe it can be important to envision something positive to work towards. I'm not sure that the imagery can be definitively said to be a vision of the future or if it is even firmly situated in time. I see reality as made of all these different temporal layers interacting. The world I depict might be described as an accumulation of history, a past future or a premonition in which the hauntings of history and the future manifest in the present. So in the work, I would say that it's about these different modes—past, present, and future—coming together and being framed by the very complicated and charged moment in which we are living.

Do you feel like printmaking gives you a particular entrance into these questions? Why this medium?

[NL]: I've used printmaking for a long time in my work; it's a material language that I have a long relationship with and that I really enjoy on a manual level. I mention that because I think that enjoyment is not beside the point. I think that care and investment in the world has to be part of the conversation when we talk about human induced climate change. Fear of the consequences of climate change is often positioned as the primary motivation for change but if we aren’t also driven by care then I think we’ll never shift things in the way that we have to.

It's also one of the older means of mass production. As a medium it points to the technological capacity to produce a huge amount of stuff which ultimately impacts the world that we live in. So printmaking points to the technologies and modes of production, consumption and value that have had a huge hand in shaping human induced climate change.

Also, the materials are pretty toxic. They depend on resources and processes that represent quite a large measure of harm to the environment. That returns us to the beginning of the conversation where I see my complicity in this whole process. Even as I make work that engages these questions around human induced climate change, I also participate in it. I'm not choosing these materials specifically to reflect that complexity, but I recognize that they inevitably become part of the content and narrative.