This Is Who We Are: Shane McCrae

Here, we talk with Professor Shane McCrae about why true poets are always abandoning themselves, how he starts writing poems, and the best ways to find one's own poetry.

This Is Who We Are is a series featuring Columbia School of the Arts’ professors, covering careers, pedagogy, and art-making. Here, we talk with Professor Shane McCrae about why true poets are always abandoning themselves, how he starts writing poems, and the best ways to find one's own poetry.

Associate Professor Shane McCrae discovered his passion for poetry on October 25, 1990. After watching a movie during high school about someone who had read Sylvia Plath—and had thought about suicide—he felt so inspired that he wrote eight poems that day. In the following months, he compulsively read renowned poets such as Plath, Ann Sexton, and Linda Pastan and decided to make a vow: he would either become a poet or life was not worth anything at all.

“Before that discovery, I didn’t have an urge or desire to do anything,” he said. “The future was dangerously looming, but poetry came to my rescue. I didn’t have any special skill at it. I was exceptionally bad at it, but because I didn’t know anything about it, I went on and I decided to commit my life to poetry.”

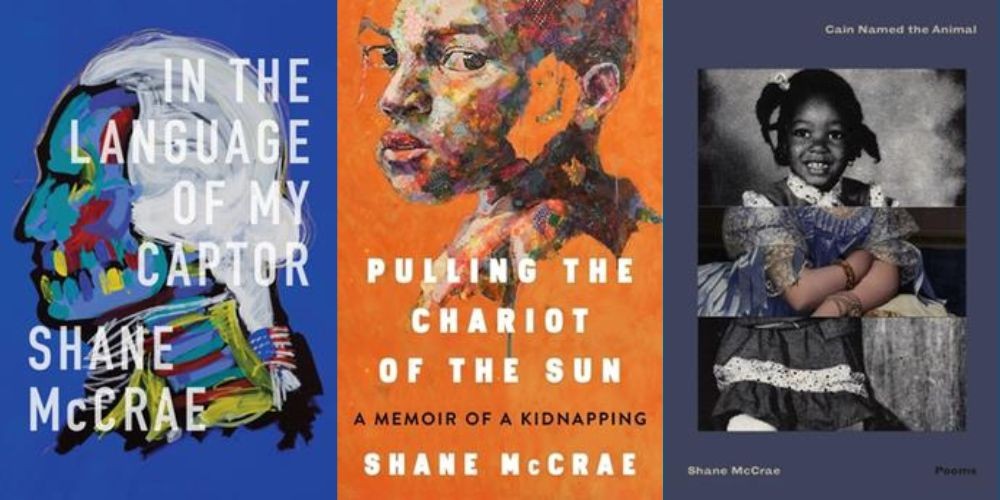

Shane McCrae has published several poetry books, among them In the Language of My Captor (Wesleyan University Press, 2017), which was a finalist for the National Book Award and won the Anisfield-Wolf Book Award, and The Gilded Auction Block (2018), which was a finalist for the Los Angeles Times Book Prize. His poetry has been recognized for its lyrical beauty, thought-provoking intelligence, and ethical urgency, and has been included in many anthologies. Recently, the American Academy of Arts and Letters announced that McCrae was awarded the prestigious Arthur Rense Poetry Prize for his contributions to the field, along with a cash prize of $20,000. “McCrae is a shrewd composer of American stories,” wrote The New Yorker. “His poems often piece together, for a striking effect, swatches of material from divergent sources: word salad from one of President Trump’s speeches, a letter from an ex-slave, lines of poetry from Sylvia Plath and T. S. Eliot, and echoes from McCrae’s tormented childhood.”

McCrae's poems often recount his early childhood years, turbulent personal journey, and an interest in the role of race in shaping these experiences. At the age of three, he was kidnapped from his Black father by his white grandparents and was raised believing his father had abandoned him. McCrae's white supremacist grandfather subjected him to abuse to erase his Black identity. "What if in Heaven we could have white things / And not be white how would we know / How good it was if it was good for everyone," McCrae wonders in Sometimes I Never Suffered. When he was 10, his family relocated to California, where he suffered abuse by other boys. He eventually dropped out of high school and became a father at 18. McCrae acknowledged once that “being alive in the world makes it difficult to mourn the world,” highlighting the paradoxical relationship between life and grief that populates his poems. We are constantly exposed to suffering and the fact that everything changes and disappears. But, at the same time, being alive means having a sense of agency and finding meaning in one’s experiences.

Despite his challenges, McCrae continued to pursue his education, attending Chemeketa Community College and graduating from Linfield College in McMinnville, Oregon. He later earned an MFA from the University of Iowa in 2004.

“I started to get serious about poetry when I was 17. I realized I was behind, so I decided to read many books at once,” he said. “When I started studying for my MFA, I had a really good handle on the English language canon, for example, a perfect sense that I had read most of the major works of poetry in it. When I was doing the MFA, I realized I was from a different socioeconomic class. There were advantages to that. Of course, being poor and not having money is not an advantage. But concerning my peers, I felt a bit more self-motivated.”

Roberto Bolaño's book The Savage Detectives (Picador, 2008) portrays the poet as a rebel who seeks to break free from societal and linguistic constraints to access a more authentic reality. He describes the true poet as someone who keeps abandoning himself. I used Bolaño’s quote to ask McCrae not about poetry but about what makes a true poet. “It’s a good question," McCrae said. "A poet is anybody interested in utilizing language in a compressed way to explore the world in their own thoughts. When writing a poem, you have to get your self-consciousness and ego out of the way. Writing a poem is mostly about listening, allowing language to lead you wherever it will. So, in a way, [poets are] always abandoning themselves.”

McCrae's poems often start with interesting sounds or syntax arrangements, as he listens to language to discover what comes next. “Once I get the first line, I start to listen to know what comes next. In that way, I can force a poem to start but can’t force a poem to be written. A phrase will just occur to me—sometimes [from] listening to people in the metro or students. Then I want to write in response to that.”

As our discussion continued, I pivoted to Elizabeth Bishop's philosophy that poetry should flow from the unconscious. In other words, a poet must have the patience to wait for inspiration to strike. Bishop asserted that a good poet cannot be in a hurry to create. However, McCrae's impressive output belies that notion, as he has proven to be a poet who consistently puts out new work every year.

“Everybody writes at their own pace,” he said. “Bishop definitely seems to have had a lot of patience. Some poets write several poems a day, others several a month, others just a few per year. You can't really form a poem. Yes, I’m sure that in the history of humankind somebody has forced upon themselves to write a poem, but I think it is extremely rare.”

McCrae has published over a dozen books of poetry since his debut collection, Mule (Cleveland State University Poetry Center) came out in 2011. “I’ve written too many poems,” he said, laughing, “but I wouldn’t change it.” He continued: “The Band REM was releasing an album a year in the 90s. That was the normal pace. And every album was reliable! Really good. I thought: if they can release an album a year, with all the touring, why can’t I write a book of poetry a year? I no longer live according to that idea, but it made much sense to me.”

Today, McCrae's process of writing poetry is a difficult balance between allowing a poem to happen and maintaining one’s own happiness. "If I don’t write for any stretch of time, I’m very unhappy. If I’m not writing, I’m irritated about not writing.”

As my conversation with McCrae drew to a close, I asked him about his relationships with his students—and how he manages to get the best from them. “As a teacher, you have to learn to listen to students. That’s something that one is constantly learning. Before you start teaching creative writing, you have to forget the idea that your students are going to turn out a certain way and that you can only allow them to write a certain limited kind of poem. You have to learn that the student’s poetry will be what the student’s poetry will be. Your job is to make it the best version of itself, not a version of the kind of poem you would like.”

As a teacher, he doesn’t focus on generative techniques in class to stimulate creativity. “Partly because it makes me nervous," McCrae confessed. "I don't want my students to depend on me that way." Instead, he encourages his students to always be available to write and to be ready to pin down their ideas whenever inspiration strikes. He cited Henry James, who said that a writer is a person on whom nothing is lost. "One must always be listening, always be ready. When ready for a poem, one listens to what's happening around them. Writing a poem is as much about listening as it is about writing."

Shane McCrae is the author of In the Language of My Captor (Wesleyan University Press, 2017), The Animal Too Big to Kill (Persea Books, 2015), Forgiveness Forgiveness (Factory Hollow Press, 2014), Blood (Noemi Press, 2013), and Mule (Cleveland State University Poetry Center, 2011), as well as three poetry chapbooks, and one nonfiction chapbook. His poems have appeared in the Best American Poetry series, Poetry, The American Poetry Review, Gulf Coast, and other anthologies and journals, and he has been awarded the Lannan Literary Award, a Whiting Writer’s Award, a fellowship from the National Endowment for the Arts, and a Pushcart Prize.