This Is Who We Are: Leslie Jamison

This Is Who We Are is a series featuring Columbia School of the Arts’ professors, covering careers, pedagogy, and art-making. Here, we talk with Professor Leslie Jamison about empathy on the page, why she sees herself as a bowerbird writer, and how teaching influences her writing style.

On her laptop, Associate Professor Leslie Jamison has a Flannery O’ Connor sticker that has turned into her motto: “Nothing can be possessed but the struggle.” In Jamison's world, the struggle is not something to be overcome or triumphed over, but rather to be embraced as a fundamental aspect of the human experience—and her writing. In just 30 minutes after our meeting, Jamison would be standing in front of a room full of students, ready to lecture on the elusive concept of The Self. How does one make sense of something so complex, so multifaceted?

“My work benefits from the belief that all lives are full of infinite layers of meaning, which sounds hyperbolic or sentimental, but I actually believe it's true,” she said. “Almost all of my essays have a set of questions at the core of them. I'm interested in using every kind of gaze or vantage point I can, deploying multiple lives in service of a question—and one of those lives is mine.”

Jamison is a writer who defies categorization. She holds a PhD in English from Yale University, an MFA from the Iowa Writers’ Workshop, and a BA from Harvard College. Throughout her career, she has demonstrated an impressive range, moving seamlessly between genres and styles to explore the complexities of the human experience. In her nonfiction work, Jamison is equally at home crafting personal essays, literary criticism, and longform journalism, but perhaps surprising to some, she got her start in fiction.

“At a certain point, I pivoted towards my own life,” she said. “I moved to this hybrid nonfiction mode that could, like a bowerbird, make his nest from whatever is at hand. Blue flowers, blue bottle caps, bits of blue tarp. It is an endless curiosity and a desire to take whatever is useful wherever I find it.”

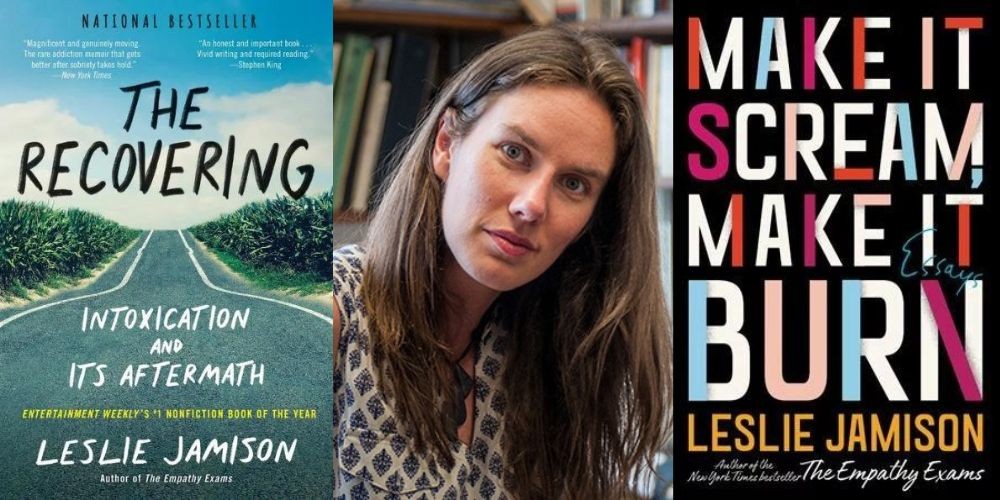

In The Recovering (Little, Brown and Company, 2018), one of Jamison's most acclaimed books, she takes a searing look at addiction and how we talk about it, blending personal narrative, cultural criticism, and reportage and offering a nuanced portrait of a disease that touches millions of lives. She started the book by acknowledging that a story about addiction “is always a story that has already been told,” but she also turned this concept on its head, stating that “suffering is interesting, but so is getting better," speaking to the paradox of addiction.

“There was a kind of reckless lifestyle that seemed dangerous, intoxicating, and infinitely interesting, this idea that you're sort of drinking to withstand certain proximity to the dark truths of human experience,” she said. “This was compelling to me as a mythology, and it's a very well-trodden mythology about art. Most of the memoirs you read about addiction drinking have 90% drinking, and 10% of ‘eat your vegetables.’ I wanted to write a very different book. I wanted half of it to be recovering and the other half about feeling sharpened into focus in more complex, compelling ways.”

Jamison frequently draws on her own personal experiences while also delving into the experiences of others. This requires a delicate balancing act, as she must navigate the boundaries between the individual and the public, the subjective and the objective, the memoirist and the journalist. I was curious about how she manages that, especially when the self, in Jamison’s words, becomes “the claustrophobic crawl space of the self.”

“When a personal narrative is read in bad faith, it is seen as an implicit statement that somebody is writing about their life because it is extraordinary,” Jamison said. “It’s a very odd idea to have. That’s not what we apply to fiction! We read fiction about ordinary people all the time. A life is not interesting because its extremity hits a 9.9 on the Richter pain scale. An ordinary life can be a subject for nonfiction like it can be a subject for fiction. When I write about my own life, it's not because it's extreme in some way. It's because it's the life I have the most and deepest access to. And I say that while believing we only have partial access to our own selves and lives, like we are kind of mysteries to ourselves. I am a mystery to myself in many ways. Teaching a course about the self is about craft and creating the self as a character on the page. You have to build an entire consciousness from scratch using scenes, action, dialogue, etc. But it's also a course about questions like ‘What is a self?’ ‘How does one begin to say who that person is?’"

Jamison's essay collection The Empathy Exams (Graywolf Press, 2014) is a profound exploration of how empathy works. Jamison challenges readers to question their assumptions about it. I asked her about the idea of becoming “the queen of empathy.” She burst out laughing and shook her head. “It never started out as a book about empathy,” she said. “It originated from an experience of working as a medical actor, evaluating medical students on how well they displayed empathy in their interactions. I started to think, god, we all use the word ‘empathy.’ It's impossible ever to understand what somebody else is feeling, and it's certainly impossible to feel somebody else's feelings. Rather than celebrating empathy as an unequivocal, uncomplicated virtue, I wanted to explore how complex empathy is. When it is just a projection or a set of assumptions about somebody else's experiences it can be dangerous, but I do believe that there is a good quest there. To try to listen and understand other people's experiences better.”

"I don't want to imagine my life without teaching. It makes my life feel fertile and engaging. What a gift, a privilege, and a thrill to be reading work by new writers all the time and talking about work in seminars with students who are deeply engaged with it."

During our conversation, I noticed that Jamison had the ability to transform my too-broad questions into small lectures about specific struggles of the writing process. For example, she spoke to the fact that one of the hardest things about writing about the self is being fair with oneself on the page. “I make myself a complicated character, which is to say, I don't want to fall into the trap of justifying all my actions, ennobling myself on the page, or trying to make myself look like some sort of saint. But I also don't want to fall into the trap of ruthlessly punishing and excoriating myself on the page. Both paths, ennobling yourself on the page and damning yourself, are self-protective and reduce complexity. And if there's any God I serve above all other gods, it's the God of complexity.”

Her phone alarm went off: we could have talked for hours, but students had started to gather for Jamison’s class. I asked her about teaching. Why does she do it? "I don't want to imagine my life without teaching. It makes my life feel fertile and engaging," she said. “What a gift, a privilege, and a thrill to be reading work by new writers all the time and talking about work in seminars with students who are deeply engaged with it. My students' voices challenge me to think in new ways, and they teach me about the world through both the content of their writing and the ways they think about what writing can be. It is truly a great joy to teach writers and then watch them three years later put those books we were working on in workshop out into the world.”

Before leaving for her class, Jamison had one final point to make. "There's a certain vitality that comes with it [teaching], you know… what's the right word?" She turned to me, seeking assistance, but her mind, much like her writing, found a solution before anyone else could. "Teaching acts as a stimulating catalyst for my writing, infusing my life with a definitive spark of electricity."

Leslie Jamison is the New York Times bestselling author of four books: two essay collections, Make It Scream, Make It Burn (Little, Brown and Company, 2019) and The Empathy Exams (Graywolf Press, 2014), as well as The Recovering: Intoxication and its Aftermath (Bay Back Books, 2019), and a novel, The Gin Closet (Free Press, 2011), a finalist for the Los Angeles Times First Fiction Award. The Empathy Exams was chosen as a Notable Book of 2014 and an Editor’s Choice by The New York Times. The Recovering was named the Best Nonfiction Book of 2018 by Entertainment Weekly and the best-reviewed memoir of 2018 by LitHub. Make It Scream, Make It Burn, and The Empathy Exams were finalists for the PEN/Diamonstein-Spielvogel Award for the Art of the Essay.