This Is Who We Are: Jaquira Díaz

This Is Who We Are is a series featuring Columbia School of the Arts’ professors, covering careers, pedagogy, and art-making. Here, we talk with Professor Jaquira Díaz about using the first person plural, writing about your own community, and why you should be wary about a redemptive ending in a memoir.

Assistant Professor Jaquira Díaz frequently peppers her workshop students with questions when they write about a particular memory. “What was happening out there? What was on the radio? What was the music about?” By prompting such reflections, Díaz inspires students to think beyond their personal experiences. She believes every personal story is invariably connected to something larger in the world. “I push students to discover opportunities to delve deeper, asking questions that encourage them to see how their story ties into a bigger narrative.”

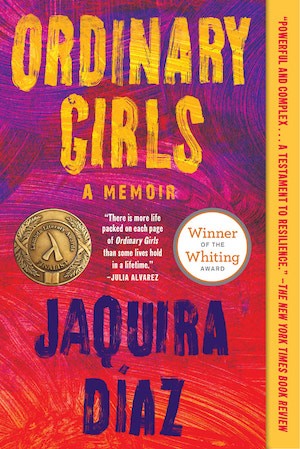

Díaz is a Puerto Rican fiction writer, essayist, journalist, cultural critic, and professor. She is the author of Ordinary Girls: A Memoir (Algonquin Books, 2019), which received the Whiting Award in Nonfiction, a Florida Book Awards Gold Medal, a Barnes & Noble Discover Great New Writers Selection, an Indie Next Pick, a Library Reads pick, and was a finalist for the B&N Discover Prize. Ordinary Girls is currently in development with FX, where Diaz will serve as Co-Executive Producer.

In Ordinary Girls, Díaz, the daughter of a white mother and a black father, chronicles her upbringing in Puerto Rican housing projects and Miami Beach. In the book, Díaz touches on her mother’s schizophrenia, the masculine violence rampant in her neighborhood, her personal battles with depression and sexual assault, and the colonial history of Puerto Rico. “I always knew I wanted to write about my communities,” she said. “But I didn’t necessarily know that I was going to write my own story. As much as I tried not to write about myself, I kept returning to certain themes. And even when I was writing fiction, I kept returning to my family as much as I tried to disguise it.”

For Díaz, writing is a confluence of her roles as both a literary writer and a reporter. Her memoir was a decade-long project that involved countless conversations with friends and family. The haunting realization she came to was that almost every woman she spoke with had faced some form of violence. It was these shared narratives that inspired her use of the first-person plural voice in her book. It wasn’t just her story—it was theirs too.

“As soon as I understood that, it became really important to affirm the existence of my community—to say, we exist, we exist in the world, even if you don’t see us,” she said. “We should also exist in American publishing. This is what it means to have Puerto Rican people that come from the Puerto Rican housing projects.”

At the heart of Díaz’s work is the intention to show a larger story, one of young girls growing up amid the working-class landscapes of Puerto Rico and Miami Beach. Her personal story wasn’t the epicenter; rather, it was a single piece in a complex puzzle. “Your personal story is always connected to a larger world,” she repeated numerous times during our conversation.

Díaz continues her exploration of place and identity in her next project, I Am Deliberate, a novel forthcoming from Algonquin Books. For Díaz, the essence of place is not limited to geographical coordinates but embraces a deeper, cultural resonance. “Whether I’m writing fiction or nonfiction, I always start writing with a place in mind. For me, place means culture, music, language, different stories,” she said. “Some people write thinking about a character; I write about places.”

As a professor, Díaz feels uplifted every time she walks into a classroom. “I think my spouse will be very upset about this, but I feel I never want to take a vacation because when I’m teaching, my writing is better. After a class with my students, I am so full of ideas, I want to start writing right away. Teaching is energizing.” Diaz hopes to teach her students that writing a memoir, as personal as it can be, doesn’t mean that you need to build a redemptive narrative arc. Writing her own book, she wanted to explicitly talk about colonialism and how it shapes people's lives without presenting a too-neat happy ending. “If I had a very redemptive ending, I was letting this colonial power off the hook,” she said.

“The problem with some memoirs is that they go after resilience and strength,” she said, “when really, what some of us artists are trying to write about are the systems that need to be dismantled. I hope to instill in my students that, as a writer, you don’t need to make the readers feel good, because the point of the writing is not always about resilience and survival. We’re making art, and art engages with readers in different ways—intellectually as well as emotionally. A memoir should lead to an intellectual conversation.”

Jaquira Díaz has been the recipient of the Jeanne Córdova Prize for Lesbian/Queer Nonfiction, the Alonzo Davis Fellowship from VCCA, an Elizabeth George Foundation grant, and fellowships from MacDowell, The Kenyon Review, Bread Loaf, Sewanee, the Wisconsin Institute for Creative Writing, and the Black Mountain Institute at UNLV, Díaz has written for The Atlantic, The Guardian, T: The New York Times Style Magazine, among other publications.