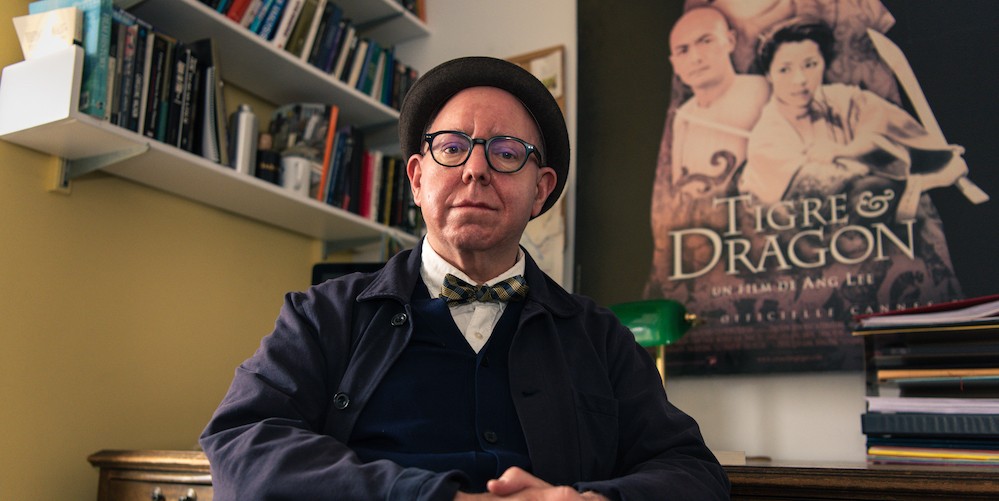

This Is Who We Are: James Schamus

This Is Who We Are is a series featuring Columbia School of the Arts’ professors, covering careers, pedagogy, and art-making. Here, we talk with Professor James Schamus about the film industry as a dream factory in need of regulations, how we’re constantly creating usefulness out of the useless, and why everything that is possible demands to exist.

The morning of our interview, Professor James Schamus awoke to dozens of congratulatory messages. The Writers Guild of America had just reached an agreement with the Alliance of Motion Picture and Television Producers after a 148-day strike, and Schamus, a member of the WGA negotiating committee, had been an integral part of the process.

“Writers are central to the industry,” he told me, his expression cheerful despite the exhausting negotiations. It was early in the morning, but Schamus was already sporting his characteristic bow tie. “The entire system depends on the skills and imaginations of people. These are channeled into creating experiences and products within recognizable genres and formats that feed the industry. But I prefer to think of us as a dream factory. A factory that needs continuous dreams to thrive. ChatGPT can hallucinate quite a lot, but it can’t dream," he said.

As a filmmaker, James Schamus has done it all. Schamus is an award-winning screenwriter (The Ice Storm, Hulk), producer (Brokeback Mountain), director (Indignation), showrunner (Somos), and former CEO of Focus Features. In addition to his industry achievements, he’s a professor at the School of the Arts, where he teaches film history and theory. Last year, Schamus earned the title of Variety's Entertainment Educator of the Year, recognizing his commitment to the art of filmmaking and his dedication to imparting knowledge to upcoming talents in Hollywood. “I’ve taught for over 32 years now, at least one semester a year, and while I don’t teach in the summer term, I am religious about making sure I don’t miss class, even for work,” he said.

Schamus has been an inveterate moviegoer since he was a child. As a middle-schooler he stayed at home on Friday nights in front of the TV watching the silent movies proffered up on the local public TV station. Late afternoons included repeat viewings of the week's "Million Dollar Movie," which were more, in his own words, like 100-dollar "B" movies, often horror and sci-fi fare. “I attended Hollywood High School, which in the 1970s was kind of like attending Times Square High School, as depicted by Martin Scorcese in Taxi Driver, if you catch my drift,” he said. “The film business was both right next door and, from the point of view of the underbelly of it that I was living in, a million miles away. I never really thought I'd work in film until I found myself in New York in the late 1980s, writing my dissertation and teaching, when I fell in with a crowd of people making independent films and dove in to help.”

When I asked him how he has managed to do all the things he’s done in the past, Schamus chuckled and said: “It’s a sad fact that I consider myself a fairly lazy person.” Then he spun a simple question into an insightful discussion, explaining why, sometimes, doing nothing is exactly what you need to shake things up and create something daring.

“Certain forms of laziness are a kind of productivity,” he said. “As an artist, you need to take time to breathe and be bored. Being busy is often a way of procrastinating by doing one thing and avoiding the other. I’m deeply suspicious of the way we instrumentalize leisure as a form of productivity. I hope those things bring as much of a non-instrumental joy as I can. We always want every second of our life, even the useless seconds, to be useful.”

He quoted Theodor Adorno, who believed that only those artworks that seem to have no clear purpose are authentic. Their practical uselessness is manifested in their autonomy. His answer reminded me of the French writer Théophile Gautier, who coined the phrase l’art pour l’art (art for art’s sake). “As soon as a thing becomes useful,” Gautier said, “it ceases to be beautiful.” I asked Schamus to elaborate.

“People say: ‘art is priceless’ but then someone buys that painting for 400 million dollars at Christie’s. Other people say: art has no value because it is not a hammer. We celebrate the uselessness of the aesthetic. But then those aesthetic practices are commodified,” Schamus said. “Then, we are talking about these useless things as if they were the most powerful things in the world. That idea hurts the artists. Adorno flips all this and says: 'Have you ever thought about the way in which we talk about art? We’re constantly trying to create usefulness out of the useless.'”

These days, mostly because of the WGA negotiations, Schamus has been far from useless. He's been ruminating about Artificial Intelligence—both its allure and dangers for the industry. He believes that his most important contribution to the negotiating committee was as a professor, bringing in protocols and a culture of academic discipline, and describing—“sometimes at a great length for despair of my fellow negotiating committee members”—the language that we use to describe the arrival and use of new technologies. “When the computers came, people said: 'Technology is after us!' No, technology doesn't do things in the way that we often express,” he said. “It’s not the technology, but the corporations and states and people that do it. We need to understand that the way we talk about technology shapes the way technology impacts our jobs,” Schamus said.

For Schamus, who recently engaged in a discussion with students about the ethical application of language-generating chatbots, we’re barely entering a new phase of relationship with AI that will shape the industry. “We don’t know yet where we’re going and what's ethical. We have to establish practical guardrails to give us at least some time to figure out ways that won’t destroy the industry,” he said. Schamus requires students to submit a document detailing their experiences with AI tools, expressed in their own words, and to include links to their chatbot interactions. This exercise, he believes, helps students understand the implications of AI in their own work, rather than just seeing it as an industry tool. “We’re to hear the student’s thoughts, feelings and ideas. Don’t let technology replace that,” he said.

“Certain forms of laziness are a kind of productivity. As an artist, you need to take time to breathe and be bored. Being busy is often a way of procrastinating by doing one thing and avoiding the other."

As a professor who is in his fourth decade of teaching, Schamus is glad that he teaches film history, criticism, and theory instead of engaging, as he defines it, in the challenging process of creativity. “I emphasize a non-instrumental engagement with your [students'] work and the work of others,” he said. He stated that he is less concerned with the amount of skill a student possesses, emphasizing instead the importance of fostering an environment where students can explore their talents without feeling pressured to use them solely for career advancement or personal acclaim. This approach, he believes, is essential in addressing the increasing levels of anxiety and stress among students. “This means creating a space with the students where thoughts and ideas can be freely examined without being used solely for work in a way that you are not instrumentalizing it. It’s about a 'not you' approach.”

This brought to mind Schamus' Twitter [X] profile. As our interview was drawing to a close, I was compelled to inquire about the personal significance behind the Leibniz quote he prominently displays on his social media account: “Everything that is possible demands to exist.” I pondered what depth this phrase held for someone who has experienced and accomplished so much in Hollywood and beyond.

His response came with a sonorous chuckle, as though the question was a new one to him. But then he reflected with a blend of light-heartedness and concentration.

"It represents a nonjudgmental acknowledgment of the endless possibilities presented to us,” he said. “Whether it's people in my classes, my colleagues, or individuals in the broader world, their existences are composed of these possibilities. Without labeling them as good or bad, this is a fundamental part of our world's structure. We may not traditionally recognize this as existence, but we do acknowledge it as demand. I believe in sorting through these demands and listening to them, sometimes even before we judge whether they are right or wrong. As a writer, there’s no hurt in keeping your mind open.”