Uncovering the Heritage Silhouette: Ruhee Maknojia ’19

Uncovering the Heritage Silhouette is a bi-weekly series diving into how tradition influences the creation of art. We interview artists heavily influenced by their heritage.

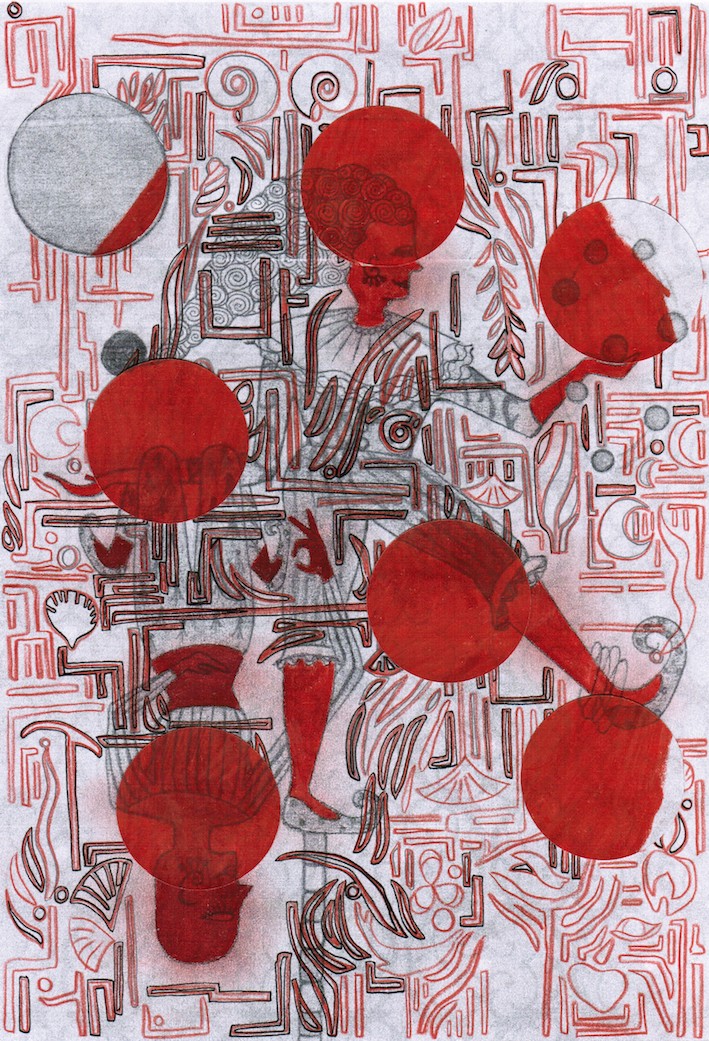

Ruhee Maknojia '19 is a New York and Houston based artist. Her conceptual research and art practice have developed around what she calls “tradition as a form”- those forces and functions that shape contemporary value systems. Maknojia’s works are influenced by the aesthetics and philosophies of Indo-Iranian Mughal gardens. She utilizes this philosophical belief and aesthetic to realigning social and traditional relations to raise questions about power, ethics, and values.

Maknojia’s art seeks to carve out illumination and peace in the milieu of violence, extremism, and fundamentalism that has infiltrated spaces of civil society by questioning what it means to open the gates between the internal space of serenity and an external world of disorder. Her art is continuously shaped and reshaped by the perforation of exoteric problems into an area of esoteric “perfection.” She uses patterns and repetition to seek beauty in abstract spaces of violence; creating is her act of protest. Maknojia works with installations, paintings, videos, drawings, printmaking, and writing.

You’ve said that your work is influenced by the “aesthetics and philosophies of Indo-Iranian Mughal gardens.” What are the gardens and why are they so meaningful to you?

Ruhee Maknojia: The gardens are a place that is regal, serene—there is no violence. One reason I’m attracted to the gardens is because there is a philosophical idea behind it. The idea that the world is a chaotic space that is extremely difficult to make sense of because there is no control over any aspect of life. And if you have enough willpower, you can create small spaces of paradise for yourself. You can carve out a section amidst all the chaos and make the paradise on Earth, that is what these gardens are. Everything in these gardens is controlled and it gives the illusion of perfection. It’s significant that none of the outside chaos can penetrate its walls. One builds four walls, all philosophical, but Mughal kinds wanted physical forms.

With my own artwork, I was intrigued by the idea of living in this world where anything could change at any moment. For example, our trajectory of life. Through my paintings and by making something I can create control and begin to make sense of the world. The paintings are my beautiful flowers that are an act of protest against the chaos. They define taking control. I am acknowledging that there is violence and purposefully creating walls.

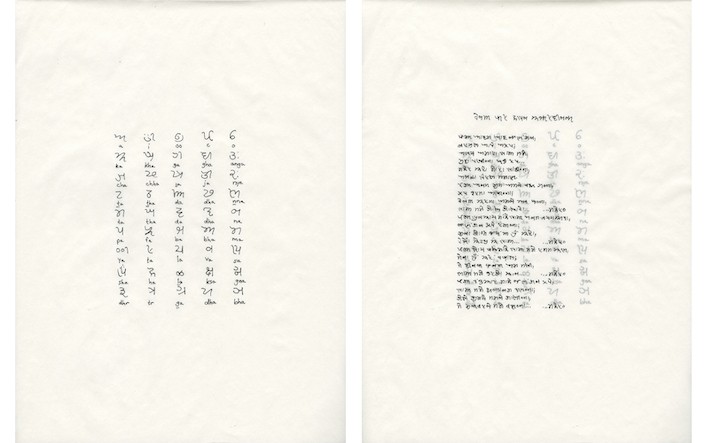

In your 2018 video animation, Khojki, that you first presented at Columbia University, viewers see some faint music playing over an image of writing. Underneath the script there are people dancing. When did this project first form and why is it important to highlight an extinct script such as Khojki?

RM: This project is one that is hard to explain, and I’ve been wanting to do more with it! The Khojki script is an invented one with the purpose of avoiding religious persecution. My ancestors converted to Ismaili faith. There was once a village where everyone spoke, read, and wrote in the native language Gujarati. When the British Empire came into existence and politics changed, a large religious division happened. The elite of this village created this script as a way to hide their religion. It is self-preservation but also their desire to be their own nation state, holding a colonialism mindset. Both were operating at the same time, wanting to be protected while wanting to be a dominant group.

What are we seeing and hearing?

RM: The sound that you hear is spoken in the Gujarati language, but the text is the religious script. This project revives this piece of history as the language is no longer used nor written, very few people know how to read the text. Depending on the region people lived in, the script would be slightly different. So there are not many people who can translate. This was my homage to my ancestors, acknowledging that it is a dying thing that will probably be completely gone in the next decade or so.

A ginan is playing in the background, it’s a devotional hymn recited by Shia Ismaili Muslims and it holds similar meaning to how we think about the garden. Each line is a verse of poetry that hints toward divine higher power. The people who are dancing in the video are singing a ginan. The dancing practice has long been erased but the hymns are still recited even though the written script has disappeared. People stopped dancing due to their desire to be a part of the elitist class. This project remembers this time when music and dancing were a part of the script.

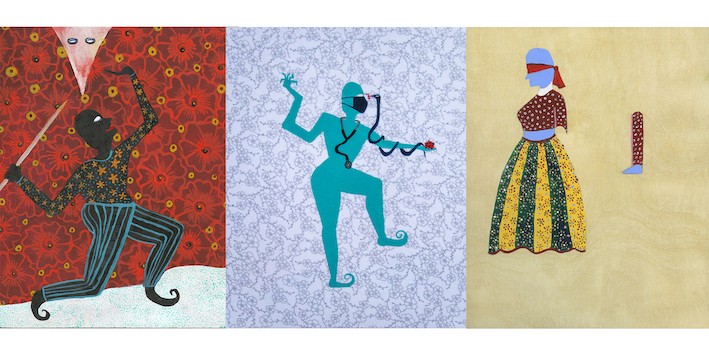

Your painting collection, Visualizing the Tradition of Folklore Through Painting portrays people in seemingly everyday life but amongst violence. Were there certain source materials that these portraits are based off of?

RM: I have hundreds of these paintings. The lore behind this project is from my childhood, when my grandma and aunt used to tell me bedtime stories. Their stories are ones that you would tell any child but were particularly violent.

One was about a king who ruled over a kingdom. He demanded a woman, who practiced a different faith than the state faith, to be his wife. During their marriage the wife secretly practices her faith everyday at 5AM while the king is asleep. He notices one night and has his soldier follow her. They catch her and so the king personally follows her the next morning. He catches her community practicing their illegitimate faith in the act of killing and eating the king’s favorite horse, which was a present to his wife. The wife puts the horse’s bones back together and magically comes back to life. She rides the horse back to the kingdom and the king ends up believing that her faith is now the true faith because he thinks its magic. The entire kingdom converts to the faith of the queen. The whole purpose of the story is that all the power lies in the queen’s hands.

I would be told similar stories one after another throughout my childhood. Someone gets slaughtered, they are magically revived, and it is always because of a woman.

How did this transform into the paintings?

RM: Their purpose was to use colors and beautiful dance figures to hide the true point of the stories. I referenced these folklores that I grew up with and also kept growing the collection with these intents. For example, there are two paintings where the figures are dressed like the KKK and it portrays racism in America in a very direct manner. The patterning takes away from that. These small portraits can allow viewers to question whether certain ideas should be normalized or not.

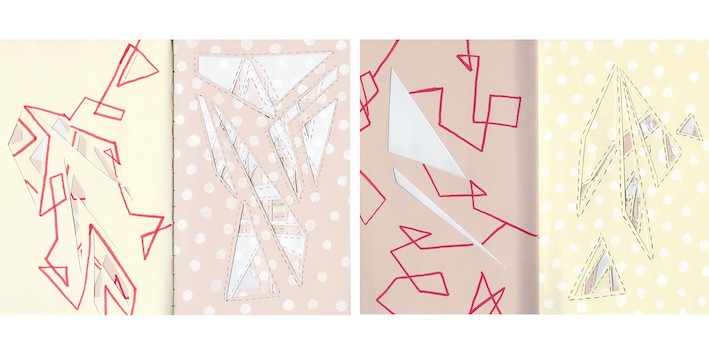

Your more recent works focus on recent events that also discuss borders, walls, and violence. Can I hear about Building on a Battered Landscape?

RM: It is my book project! There were a lot of works that were made the election year in 2016, sort of anticipating what was next. This project was posted and I realized that no one was really satisfied with the election results. I do not truly believe anyone walked away feeling satisfied, everyone on any side had great losses, mostly people feeling like they no longer have a voice. The internal landscape was filled with empty answers.

My works allow me to look at politics at a wider and softer angle. I think elections leaving such an effect can make people think about how to build back civil spaces, public spaces. This project is a reaction to thinking about these places also.

What made you want to start creating art around such topics as politics and war?

RM: In the history around me, and globally, there are many people who have been murdered for their religious beliefs. I became interested in ideas around how fundamentalism and extremism manifest in people, so I started creating work as reactions to these. There was a period in my life where I would see a lot of news of people who had access to a good education and a good quality of life yet still encapsulate these ideas. Early in my art practice, I was most intrigued by fundamentalism coming out of Islamic countries, however today I look at the issue of fundamentalism and extremism from a more global, humanitarian, and mental health point of view.

Personally, around 2015 I began rethinking how I approach these topics mentally and how art can become a coping mechanism. From there I started creating works that were always reactions to violence. It was always trying to figure out how I can counter the bad and despite the fact that I have not found an answer, this is what keeps pushing me to continue creating.

We, as a society, are continuing to traverse these landscapes as well. So we will be on this journey with you. What can we look forward to with your art? What are you working on now?

RM: I am exploring the topic of “love.’” It is a shift from responding to violence and hate which my work has been mainly about up until now. I have been working on a whole collection around what makes different people come together. I have a project coming up that I am working on with the Spanish Institute of Culture in Houston, Texas. We are working on the topic of “fusion.” I proposed a documentary artist film that focuses on the lives of couples who reside in the state who have different cultural backgrounds. Some of the couples I have spoken to come from different religions, languages, and belief systems but have worked it out. The couples all hold similar values that allow them to look beyond those differences.

The shift in work is in a way a response to the current times. The way I see it, my audience is very Western. And during times of peace, it makes sense to talk about violence as it’s a topic everyone is familiar with. During times of destruction when everyone is feeling mass anxiety, it is better to take it back and show people who have fused their lives together, essentially creating their own culture.

It recognizes that there is a facet of people who cannot ever understand the fusion of cultures, such as older generations. The people I speak to are not simply Black or white but rather can believe in one God and many gods at the same time. It is human nature to question, and it is better to do so than suffer alone internally. Nothing ever has to be right or wrong. These people all embrace uncertainty as a reality.