Uncovering the Heritage Silhouette: Noah Breuer ’07

Uncovering the Heritage Silhouette is a bi-weekly series diving into how tradition influences the creation of art. We interview artists heavily influenced by their heritage.

Noah Breuer ’07 is an American artist originally from Berkeley, California. His creative work examines themes of family, identity, labor and diaspora. His current project examines the visual legacy of Carl Breuer and Sons, his jewish family’s former textile printing business, founded in 1897 Bohemia and seized by the Nazis in 1939. Breuer holds a BFA in Printmaking from the Rhode Island School of Design, an MFA from Columbia University and a graduate research certificate in traditional woodblock printmaking and paper-making from Kyoto Seika University in Japan.

Breuer’s recent solo exhibitions include Heirloom at Penn State University Altoona (Altoona, PA, 2020), Something Borrowed / Something Broken at Spring Hill College (Mobile, AL, 2020), CB&S Werkstätte at Spudnik Press (Chicago, IL 2019) and Lucerna at Left Field Gallery (San Luis Obispo, CA 2018). His artist books have been published by the San Francisco Center for the Book as well as Small Editions in Brooklyn, New York. His work is in the permanent collections of the New York Public Library and the Watson Library at the Metropolitan Museum of Art. Breuer currently works as an Assistant Professor at Auburn University.

What is your “cultural heritage?”

Noah Breuer: It’s a hard question. I believe people pick and choose their cultural heritage, especially those who are mixed with different cultures. On my maternal side I am a tenth or more generation American with a long history of Catholicism. That side of the family fought on both sides of the Civil War; however, there has been a disconnect for a number of reasons. My dad, who I often speak more about in my art, is Jewish and a recent immigrant. I was raised going to temple. For that reason I identify a lot more with that side. People can consciously pick what part of their given heritage they want to follow and highlight. I’m sure that I could—and probably still will—do a family inspired project about my mother’s side, but it would be more difficult. Nonetheless it would be an interesting project, just not my chosen project at the moment.

When first creating this series, I immediately thought of your work. It’s inspired by the legacy of Carl Breuer and Sons, your family’s former textile printing business, founded in 1897 in Bohemia. What exactly is the history of Carl Breuer and Sons?

NB: Both my grandparents on my dad’s side were born in Vienna, Austria right before World War I and became adults who were very active in their respective fields. Actually, my grandmother was very well educated, studied in Paris, and taught English and French to Viennese people. My grandfather was in the linen trade at a company that was started by his grandparents—Carl Breuer and Sons. Carl is my grandfather’s grandfather, and the sons are Ernst and Felix. They were involved with this textile producing company that had its main financial backing in Vienna but had a factory and production facility out in Bohemia, now the Czech Republic. That business is really emblematic of a whole sleuth of Bohemia, Silesia, and Moravia textile factories as they were and still are large textile producing areas. They distributed all over Europe and my family’s factory was one of a dozen or so Jewish owned. The Jews of Prague and the greater diaspora have a mixed history in that region, but there had been sporadic points, going all the way back to the 17th century, where the King or local rulers were pretty hospitable. Jews there were able to practice their religion, own property, own businesses, and basically be somewhat autonomous. Of course, this history all ends with the Holocaust and the takeover of by Hitler’s nationalist socialists. Nazi members were installed into leadership roles for all those kinds of businesses and that became the fate of the Breuer factory.

As a result, a lot of people left, such as my grandparents who came to Los Angeles. There was this time between the invasion of Czechoslovakia and the end of World War II—between 1938 and 1942 or so—where their fate was unclear. Unfortunately, many people could not escape, including a large part of my family.

Did you always know about the factory itself? Was this a story passed down through generations?

NB: Yes, we knew that the family was in the textile business and in fact when my grandfather moved to Los Angeles, he got back into the textile business. He was a salesman because he was not knowledgeable. In no way though did this family business influence my decision to major in printmaking. The actual craft was not something that was pushed. My father was a photography professor but certainly did not push me to go to art school. If you believe in fate and that kind of thing, perhaps there is a through line.

How did you end up getting back in contact with the factory?

NB: Around 2014 or 2015, my father was doing some family research trying to find specific facts as he was creating a family book and he came across this museum in town called Česká Skalice. It is called the Czech Textile Museum that held samples from my family’s factory and other dozens of factories. I went there on a research trip in 2016 and arranged a day to visit the museum to see their archive. I found a Czech history student through Facebook to be my translator and his professor had something to do with the museum directly so through his mentor I was able to get a really great entrée into this museum.

They were extremely generous in allowing me to go into their study rooms. They brought out all of these boxes with my last name on them, which is as bizarre of a moment you can imagine. I thought I was going to be presented with a few pieces of fabrics, but it exceeded my expectations as they had dozens of swatch books, these 4 x 6 in pieces of materials. They had a lot of larger samples also that stemmed from ties, handkerchiefs, bedspreads, table linen, napkins, and window drapery, all in ranging preservation qualities. It was just such a fantastic experience and it was immediately clear to me that I was getting what I hoped for, which was a lot of source material.

I brought a camera, and my translator brought a small scanner, so we got high quality primary source material. We only had a day and I definitely want to go back, for a number of reasons. Those materials, in digital form, have become my springboard for making all sorts of works in all sorts of media, mostly print media, installation, print on paper, glass, and textiles.

Where did you begin in trying to imagine the original products?

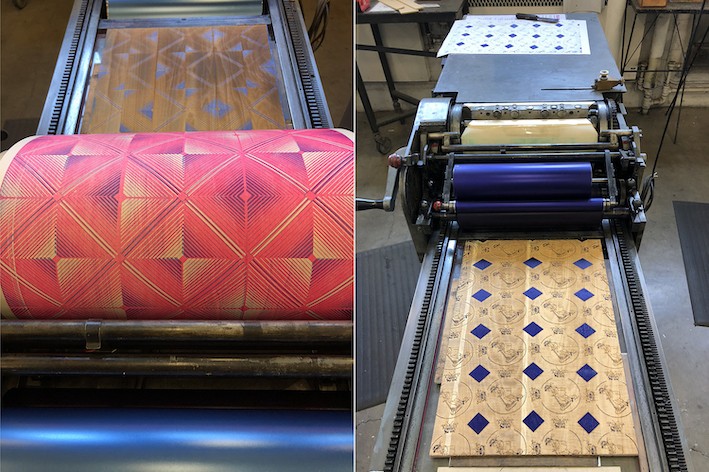

NB: That same summer I had an invitation to do this residency at the University of Oregon that they called the Summer Craft Forum. The art department there invites one or two artists per media such as printmaking, jewelry, ceramicists, and more. They gave us access to their university studios and the help of some student assistants. I was only there for two weeks, but I was fresh off this trip. I immediately put together some interesting prints just to see if I could reproduce some of these designs on paper. For two weeks I made screen prints from my digital collection and after even well into the summer when I returned to my own university, I pretty quickly realized that I needed to learn how to print on fabric.

The works that you create become a continuation of your heritage in a way. They transform with your re-interpretation. I often think about authority and ownership when creating. It’s a relevant issue especially to many born in America from immigrants, whether it is okay to create from others’ lived experiences. What are your thoughts on this?

NB: This definitely raises some questions about authorship and of course appropriation. I’m certainly using source materials and using it in my art. I feel very much empowered to use this material and I have no issue as the materials are directly from my own family. But it is interesting so far as whether the designs of the artworks were done by my actual family rather than their workers, as it was a factory. It is actually something that I don’t have the answer for. I wonder what role my great grandfather had in the business, I think it’s more on the business side than on the design, but I do not know for a fact. Now I am in the position of being the artist who does get credit whereas there are these designers who worked for my family that obviously did not. I think it is a funny parallel in fine art print production in which the fancy artist gets the credit and the printer is uncredited. So, there is that kind of question of labor going on.

The secondary issue of labor that I think is present in the work and is worth considering, is the role of this factory and its role in the lives of those in the town it supported. They provided work and grew from 1897 to 1939, and it is basically a good case study of a million businesses in Europe that fell because of the war.

How do you choose what to retain or give up from the original Carl Breuer & Sons?

NB: When thinking about what stays and what goes, I try to make some less repercussions on paper. Because the fact that I was changing the context from mass produced industrial print on linen to fine art edition or just sometimes unique print freed me up. This was because first, I didn’t have time or resources to reproduce mass produced textiles nor the training, as I never worked in a factory or similar situations. In fact, the highest level of print I’ve worked on is at grad school at Columbia, at the Neiman Center, and even that is very much fine art. I then had to force myself to think about what would be interesting.

When deciding what to take and what to leave when reframing it and changing the context, I think this is a constant in artwork. I am making it into something completely directly, a rarefied object or commodity, a very 20th and 21st century fine art language. There is some weird economic alchemy going on there.

It’s insane how much power one can have over such pieces! You can portray history in a particular way, in this case a vividly beautiful way. Your works become the cover for textile factories during this time in a specific place. I’m curious about your goals for recreating and/or creating from history? Are there intended impacts you aim for?

NB: This is a question that I have been thinking about more and more as I continue to work on this. And all projects need to evolve and continuously stay interesting. I often step back and look at what the project is, at the whole forest instead of just the trees. I think in many ways it is a restoration project, especially as a starting place.

There was a time after Czechoslovakia opened up after 1989 to the West and wasn’t a Communist country anymore. A lot of American Jews tried to put claims on things that were lost to the Nazis during the war, things like houses and businesses that had been out of their families for fifty years. So many people asked me whether or not I had a claim on all of these items. The short answer is no, because unlike objects and property that were stolen from Jews or stolen from Nazis by the Soviets, this archival material that the Czech Textile Museum now has ownership of was donated by the company before the war. So that museum has existed for more than 100 years and they were actively collecting things in the 1910s and 20s. Because it wasn’t a big fancy art museum, the Nazis never stole all the stuff in it. All these materials sat there in the museum until I saw them. So, I do not have a claim, and god bless the museum! This is why people should donate to museums as they do an amazing job collecting and preserving things.

There certainly were objects, artworks, materials from my family’s company that would still be with us if the war had not happened. So that is where this becomes a resurrection project. It is a grand serendipity that I, a trained printer and artist, have the power to resurrect parts of it. And it is personally one of the most satisfying things about this project.

I saw in the earlier years with Carl Breuer & Sons you were working with screen print on paper, then moved to woodcut on silk and linen, then UV reactive dye on cotton, and finally onto the 3-dimensional glass. What was the decision process? How did the work shift?

NB: In projects before this and here, I am, on the conceptual side, always mining some sort of collection and responding to it. On the material side, I’m really curious about craft and different kinds of techniques for making. That more than anything is important. When I went to Rhode Island School of Design, I originally thought I wanted to be a painting major, but I fell in love with printmaking because you can do a lot of the same mark making, color, and painting tropes while learning about the process of printmaking. There is a lot that goes into making an image in printmaking. In my post education life and especially in the past ten years I really tried to expand my material making knowledge, craft knowledge. I am definitely of amateur level skill at all these new crafts: textile, printing, woodworking, and most recently, making glass sculptures. So essentially, I think every new stage comes from new ways of thinking.

The step from paper to textile was obvious, it was important and conceptually relevant, and I want to continue doing that. The step to glass was in relevance to the main sort of visual art exports from Bohemia and Czech Republic, which is crystals, special Czech cut glass and such. I had shifted over to glass and have been recently working on that.

How did you start utilizing glass in this piece?

NB: I had this great residency two summers ago in 2019 called Bullseye Projects in Emeryville, California and there I had glass workshops where I learned lots of printing techniques but specifically, I learned some kiln forming techniques. This is where you manipulate the glass by heating it in the kiln. You put molds under the glass so that it can slump down on top of other objects, the technique is called ‘slumping.’ That technique was really an epiphany for me.

I went into the residency knowing I could print enamel on glass, and I had seen a demonstration where you could push glass frit, these tiny macerated powder sugar types of glass, and fuse it onto other pieces. So, I always knew I could do various printmaking on glass but didn’t fully understand and appreciate how you could utilize slumping. For some reason I also came into this residency wanting to make glass that looked like fabric. Slumping easily became the most effective way I could put an object under a flat sheet of glass sometimes with a printed image, and then fire the kiln up to 1200 or 1300 degrees. I would leave it in there overnight and it would flow, drape, and create folds. I particularly loved that it created this phase for unexpected actions to happen. What drips are to painters, what expandable foam is to sculptors, this slumping maybe is to glass artists. The glass is liquid and wants to flow, change, and captivate.

These pieces in particular I was trying to make round, and I had found these patterns that were original designs. They were for tablecloths and there were several different designs that I wanted to try to reproduce and imitate. I really like the idea that I could make this glass tablecloth into a sculpture. Slumping allowed the project to self-support. I also made these slightly smaller ones—sort of placemats—and after I made them I really thought they had a shroud effect. There is something beautiful, but I felt there was a funerary reference happening. They looked like burial shrouds and they are covering a place setting for someone who is no longer there.

What is next for your Carl Breuer & Sons project?

NB: I am working on a couple pieces that are four foot by two-foot sheet of glass in a polygonal shape with a sitting steel frame around it. I will be showing some stuff like that next fall in a show in Maryland. I also am very interested in doing some public art installation as the glass is so seductive when backlit by the sun. My ideas for those now have to do with recreating architectural structures. I have designs that will help me recreate certain buildings such as the temple or family homes that were in the Austro-Hungarian town of Königinhof where the Carl Breuer & Sons factory was. I would like to recreate part of facades of buildings and maybe impregnate those with glass, in a racial white read way. That is my vague sketch of the large installation piece I have in mind.