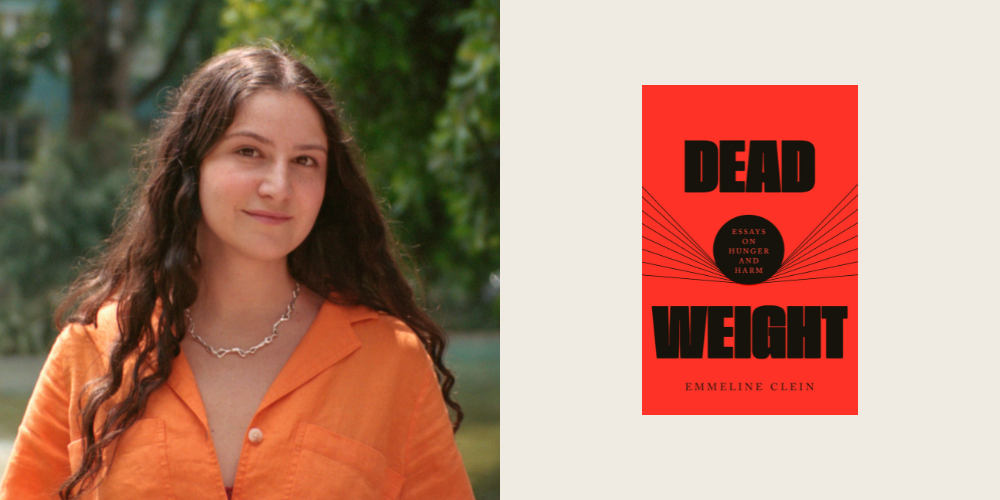

Emmeline Clein ’22 Investigates Disordered Eating in Debut Collection

Dead Weight: Essays on Hunger and Harm (Knopf, 2024), a debut essay collection by Writing alumna Emmeline Clein ’22, begins by asking the reader: “Have you ever seen a girl and wanted to possess her?” What Clein refers to here is not a real girl, but rather a pervasive emblem of Western beauty standards. If the reader answers yes to the above question, she continues, they’ve experienced “girlhood”: something she refers to in her book as, “Less a gender or an age and more an ethos or an ache.”

Dead Weight surveys this ache of girlhood, examining the "idols" presented to young girls through various forms of media: the women––both real and fictional––whose struggles with disordered eating and mental health are depicted as appealing. She writes, “Sobbing and throbbing, a lot of the most beloved icons of girl culture are very, very sad, and very, very skinny. They are beautiful, and their sorrow only adds to their sex appeal.”

Clein has herself struggled with disordered eating since she was 12, and said she initially saw this "ideal woman"—the languishing, starving girl depicted in books and media—as gospel, not a cautionary tale.

“A lot of girls are inducted accidentally early on into this kind of skinny, sexy, sad girl cannon of figures with self-harm coping mechanisms that they've been taught by society are ways to get attention and affection and love and to satisfy a very natural yearning to be seen,” Clein said.

"Sobbing and throbbing, a lot of the most beloved icons of girl culture are very, very sad, and very, very skinny. They are beautiful, and their sorrow only adds to their sex appeal."

Much of the aim of Dead Weight is to construct a nest for this yearning through a bricolage of cultural criticism, literary analysis, and personal anecdotes. To analyze the myth of "girlhood," Clein wanted to engage with a wide variety of media and stories. She evaluates television shows which are often not taken seriously—but are beloved by teenage girls and therefore highly influential––alongside literary novels and Pulitzer Prize-winning works such as Anne Boyers’ The Undying. In bringing together these varied depictions of women and traditionally feminized mental health issues, Clein argues that eating disorders are not just a clinical illness and epidemic, but also a cultural, political, and socioeconomic issue.

“My book is very interested in the way that diagnostic labels are constrictive and can worsen mental illnesses by making you believe you're just a specific set of symptoms that can only be addressed in a specific way—rather than [acknowledging] that you've been a pawn to a lot of larger structural systems,” she said.

The public reception of eating disorders as divorced from the systems and societal pressures which uphold them, according to Clein, stems from the fact that many issues faced by women are dismissed. “We, as a society, don't take women's pain as seriously as the pain of men. Women's pain is understood as an emotional manifestation rather than a manifestation of political despair,” she said.

This impulse to diminish feminized mental illness is also rooted in a capitalistic urge, Clein said. “Our beauty ideals, which are incredibly racist and misogynistic, are upholding a series of extremely profitable industries,” she elaborated, adding that many of these ideals are only attainable through a great deal of self-harm. “If we recognize that [these ideals are] a lie, then the entire weight loss industry falls apart and so does the eating disorder treatment industry, both of which are extremely profitable industries.”

"We, as a society, don't take women's pain as seriously as the pain of men. Women's pain is understood as an emotional manifestation rather than a manifestation of political despair."

According to Clein, honest, unglamorized literary depictions of disordered eating are so important because they directly combat these assumptions. “In literature, you can be truly open about your experience and you can situate yourself within the societal structure as opposed to the structure of patient-doctor or patient-mental hospital, which are spaces where you're taught a very specific narrative about yourself,” she said. "In literary depictions, you can put your story alongside other women, and seeing how many of our stories have been a giant collision into each other's can be incredibly enlightening and revelatory in terms of fostering a sense of solidarity—and a realization that it's not your fault.”

The most effective form of treatment, for Clein, was not only reckoning with the social origins of eating disorders but also having meaningful conversations with those who’ve faced similar struggles. “A lot of my recovery was predicated on educating myself and learning how much I had been a pawn to forces that I did not want to continue entrenching and strengthening by self-harming in the way that those forces wanted me to,” she said. “And it was also predicated on having a community of people in real life who I could talk with about these things honestly and who were also trying to unlearn the same things I was trying to unlearn." It's for this reason that Clein's book is built, in part, on other women's stories—people Clein spoke to about their shared experiences or stories she encountered through books, blogs, movies, and other media.

While Clein does discuss her own struggles with disordered eating throughout the book, much of the book's focal point is this community she’s fostered and the experiences that could largely be considered universal. The final paragraph of Dead Weight’s prologue reads: “Can I tell you a story that isn’t mine? I’m going to be doing that a lot, but it’s because I can’t tell where you stop and I start, or I don’t think it matters, not when we’re locked on the same ward. Besides, so many of our stories are so similar, I slipped into yours in my dream last night, and you’re welcome here whenever you want. Let me make you a drink and tell you about someone you might have been.”

Clein reiterated this sentiment, saying that Dead Weight is, above anything else, a requiem for those who have been unable to share their experiences. “I don't think my story is any more worth hearing than the ones I had to cut from the book for space,” Clein said. “The book is meant to be a project of amplification and attention to women whose stories have been forced to be as small as the bodies they were taught to want.”

Clein will discuss Dead Weight at the School of the Arts's Crisis and Desire event on April 11, 2024, also featuring Associate Professor Leslie Jamison and alumna Eliza Barry Callahan '22.