Alumni Spotlight: Wendy Jones '81

The Alumni Spotlight is a place to hear from the School of the Arts alumni community about their journeys as artists and creators.

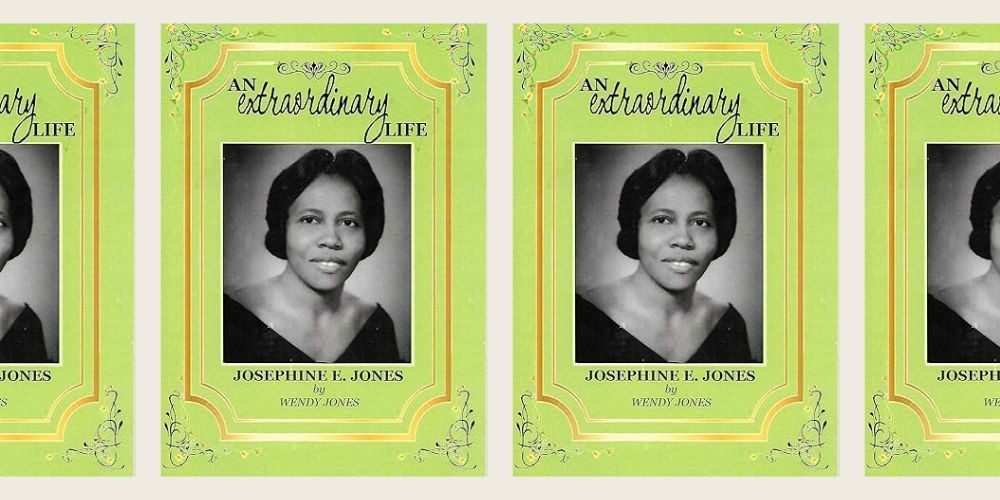

Wendy Jones '81 has completed a biography of her mother, The Extraordinary Life of an Ordinary Woman: Josephine Ebaugh Jones which will be published in 2016 by the small press she has founded, Ida Bell Publishing, LLC.. A former tenured English professor, Wendy Jones has, since 2005, run a business, Writing Maven, LLC, which helps people write college essays, résumés, and wedding vows. The company also tutors students taking the PSAT, SAT, and the ACT. Wendy’s short story, Savannah, appeared in 1996 in the anthology Illuminating Tales of the Urban Black Experience published by Penguin books. Ms. Jones wrote an award-winning first play, In Pursuit of Justice: A One-Woman Play about Ida B. Wells, starring Janice Jenkins, which made its debut in 1995 at the H. A.D. L.E.Y. Players in New York City. It won four AUDELCO awards. The play has been revived several times, including a one-hour version at Payan Theater in New York City and a full performance in New Rochelle. The one-hour version has also been produced for churches and schools in New Jersey and New York. Wendy has a B.A. in Literature from Yale University. As Scholar of the House (Yale’s independent study program), she wrote a novel, Shorty, to fulfill her graduation requirement. Ms. Jones also earned an M.F.A. in Fiction from Columbia University. There she also wrote a novel, Jordan, to fulfill her graduation requirement. Wendy Jones lives in New Jersey with her family.

Was there a specific faculty member or peer who especially inspired you while at the School of the Arts? If so, who and how?

I was inspired by three peers. Over tea at a nearby restaurant, Margie and I talked about what we each thought worked and didn't work in the latest stories we had each presented to the class. Speaking with her one-on-one was a richer and more intimate experience than the class discussion. Connie, that was his nickname, had no problem talking to me in class about my character development and structure. I felt connected to his work too, and was able to offer helpful comments. Eric and I read our respective stories aloud to each other and discussed them before we presented them to the class. All of us felt a warmth towards each other's work. We all knew where each of us was attempting to go with our writing, so we were able to help each other to get there. My three fellow writer-friends were Asian-American, European-American, and African-American respectively.

How did attending the School of the Arts impact your work and career as an artist?

The School of the Arts gave me the time to create a body of work which I built on after I graduated. Although I have continued to write new work and revise old work, it has been more difficult to write in the spaces between the time necessary to make a living. The small press which I founded, Ida Bell Publishing, LLC, will publish my book about my mother's life, my first book, The Extraordinary Life of an ORDINARY Woman: Josephine Ebaugh Jones in 2016. It also gave me the chance to try new forms. I wrote my first real play with Samson Raphaelson. I later wrote In Pursuit of Justice: A One-Woman Play about Ida B. Wells which was first produced in Harlem and later went to an Off-Broadway theatre and won four Audelco Awards. I don't think I would have written that play without having taken that class with Mr. Raphaelson. I knew he wrote the Jazz Singer, but was too shy to discuss it with him. He told us great stories about it, though. Talking about all the money he made in Hollywood, he said he gave it to the "money boys" and they lost it all in the Depression. He said, "When you make a lot of money, do what you want with it. Paint a boat in solid gold. At least you will have had some fun." In addition, the School of the Arts "Meet the Agents Night," was extremely helpful. I was able to find out immediately that the traditional publishing structure had no place for or understanding of the importance of children's stories featuring African American children. I was told that the market for children's books was "glutted." However, I knew, as a mother searching for books to read her son, that there were too few books featuring African American children. This encounter made it obvious that if I wanted my children's book published, I was going to have to publish it myself. Instead of waiting three months to hear this news, I heard it in less than three minutes. In 2013, 3200 children's books were published in the United States, 93 of them included African-American characters. I don't know how many included Latino or Asian American characters. I intend to help change that statistic through publishing my children's books and those of others, which will include stories that portray all people of color.

What were the most pressing social/political issues on the minds of the students when you were here?

Columbia was building a gym in the neighborhood, which was adjacent to Harlem. However, it was not going to allow the community to use the gym. There were angry exchanges about this between community members and the administration. Another incident showed me in a very personal way how deeply Columbia University was at odds with Harlem. As part of the staff of the literary magazine, I think it was called Columbia, I attended a meeting to discuss where the reading, which I think was a fundraiser, would be held. One of my fellow writers said, "As long as Columbia is so close to Harlem, there is no way we can have it here." Many of my fellow students knew that I was a Yale graduate, but only my close friends knew that I was a native New Yorker born and raised in Harlem. I said to him, "I am from Harlem. If you are going to make racist comments, wait until I leave the room." There was silence in the room. The reading was held downtown so those who were afraid of coming to Harlem could attend. In addition, Columbia's presence was changing the neighborhood in ways that the original residents resented. When I didn't bring my lunch, I ate at a local luncheonette on Amsterdam Avenue. I stayed away from Broadway because it was too expensive. The owner told me that his business used to be busy all year round. Now that Columbia had bought apartment buildings and turned them into dorms, his business took a nosedive during the summer when the students left. This is the now familiar story of universities taking over a neighborhood. It happened with NYU in Greenwich Village and with Yale University and the Black neighborhood in New Haven. And finally, this was during the time that Sydenham Hospital closed. Along with one of my fellow writer friends I went to picket the closing. The hospital was not a good one, but except for Harlem Hospital it was the only one in the area. The picketing did no good; it was turned into an apartment building.

If you could revisit any piece you created during your time at the School of the Arts, which would it be? Why?

I don't have to revisit any piece. I have been building on the work I wrote during this time. This, I tell people who are considering an MFA program, is the beauty of it: You have time to create a body of work. In fact, my novel, which will be published after the story of my mother's life and my children's book, was my final project. I jettisoned two thirds of the book and started again with the best third. In the future, I will also publish a short story collection which will have several stories that I first wrote while I was at the School of the Arts and have revised over the years.

What was your favorite or most memorable class while at the School of the Arts?

Oh, great! Now I have a chance to talk about Richard Yates. I'd met him briefly when he came up to Yale, he was a friend of my mentor, David Milch, but it was at the School of the Arts that I took a course from him. We read fiction and chewed over what we read as writers. My favorite class with him was our discussion of Madame Bovary. This is one of my favorite books and I didn't mind reading it again. One of the class members asked if Emma Bovary was a sympathetic character. I was quite angered by what she said. It did not seem to be the comment of an insightful reader. I wanted to say, "This is not a soap opera. We don't have to like the character. We just have to believe that she's real, that she's a three-dimensional character." However, I could not think of a way to say this diplomatically, so I said nothing at all. But Mr. Yates found a way to say the same thing in a humane and caring way. I really admired that. When I visited Boston, I went to see him. It was good to talk to him about my work. He told me that I had an "embarrassment of riches." From this I understood him to mean that I should finish these works in progress and get them out into the world. This is what I have attempted to do. I think I got so much out of his class and out of talking to him because he reminded me so much of my talented, creative, and self-destructive relatives. I miss him.