This is Who We Are: Shrihari Sathe

This Is Who We Are is a series featuring Columbia School of the Arts’ professors, covering careers, pedagogy, and art-making during a pandemic. Here, we talk with Adjunct Associate Professor of Film and alumnus Shrihari Sathe '09 about world cinema, what it takes to be a producer, and his directorial debut, Ek Hazarachi Note (1000 Rupee Note).

As a producer and director, Shrihari Sathe’s films cover the breadth of human experience. From evocative dramas on teenage sexuality in Eliza Hittman’s It Felt Like Love (2013) and Beach Rats (2017); to noir thrillers set amidst the seedy world of child sex trafficking in Partho Sen-Gupta’s Arunoday (Sunrise) (2014); to magical realism in his latest film, Francisca Alegría’s The Cow Who Sang a Song Into The Future (2022), Sathe's films are impressive in their subject and tone. The Cow Who Sang a Song Into The Future, set on a Chilean farm facing environmental decline, won acclaim at Sundance earlier this year. “What excites me as a producer versus what excites me as a director,” Sathe told me over Zoom, “is that I am always looking to find the best person to tell the story.”

Sathe was intrigued by world cinema at a young age, but it was tricky to find growing up in Bombay. “Cable was pretty new,” he said. “It wasn’t easy to access non-Hollywood or non-Bollywood cinema so the only possible way for me to look at film was through the British Council Library and the American Library.” Using these resources, Sathe watched Italian neorealist films and the French nouvelle vague. “I distinctly remember watching Bicycle Thieves by Vittorio de Sica, watching Godfather, watching Breathless by Goddard. I think I saw That Obscure Object of Desire, the Luis Buñuel film too.” Sathe began to appreciate cinema as a language––not merely a form of entertainment, or even art. “But that was really just an entry point,” he said. “When I got to college in the US, that was when I really started to immerse myself in cinema.”

Sathe enrolled as an Economics and Film major at the University of Michigan, only to discover––one semester in––that he didn’t have much of an “aptitude” for economics or math. He switched majors, dedicating himself to film and filmmaking. He designed a new program of study, titled ‘Global Media and Culture,’ which opened his eyes to different kinds of storytelling. He examined the relationship between a country’s cinema and its culture. “I explored film industries from all over the world—Korea, Australia, England, France, South Asia; even trans-Atlantic relationships. So how cinema from Latin America influenced cinema from Africa and vice-versa.” Sathe also studied how ethnography influenced filmmaking. “That was something that really interested me. I started learning how different filmmakers from different socio-economic and cultural backgrounds were approaching the medium. Sathe dabbled in making his own work too, mostly experimental films and video art, but a lot of the classes he took at University of Michigan were theoretical and analytical. Sathe wanted to gain practical experience as a filmmaker so in 2005 he enrolled in the MFA program at Columbia, with an emphasis on creative producing.

“My goal was to really learn the craft of narrative filmmaking and further my skills as an organizer, a person who puts things together.” This, Sathe said, is the vital characteristic of a producer: to be, as he put it, “somebody who makes things happen.” This skill was put to the test in his third year of the MFA program. Columbia requires all producing students to do an internship, so Sathe secured one back in India where, for three months, he would gain set-experience and the skills necessary to make it as a producer. What started as a three month stay became an eleven month stint on a single movie––a staggeringly long period for a single film. “It filmed for over 100 days and I was on set for close to 80% of it.” No doubt, the experience was vital for him. Sathe came back to New York, finished work on his thesis, took advanced screenwriting classes; and, in 2009, began producing films professionally.

Since then, he has produced or co-produced over fifteen features, consulted on two documentaries, produced a docu-miniseries, and countless shorts. As a producer, it’s essential to Sathe that he match his projects with directors best served to tell those stories. “The vision of the director and the intent of the filmmaker is really important,” he said. But that doesn’t always mean he and his director have to see eye to eye. “In some ways, a project gets more exciting when there is creative disagreement because then you’re pushing each other to do your best. I think the producer’s role is to challenge the director to make their best work in the safest way possible.” If Sathe and the director have creative differences, then the director’s job is to convince the producer that their vision is right. “That’s challenging them to further their own creativity.”

In 2013, a short story about a thousand rupee note by the Indian writer and journalist Shrikant Bojewar landed on Sathe's desk. As he began work on the project as a producer, he quickly realized he also wanted to direct the film. With two producing successes already under his belt, financing went more quickly than it would have otherwise; and Sathe was eager to recruit a team he could trust for his directorial debut. He brought on fellow Columbia alum Ming Kai Leung '06 to photograph the film, and researched and interviewed countless others for crew roles. In the end, his team had as many as 90 people, drawn almost entirely from India. He smiled a little, recounting the number. “The model of making a movie in India,” he said, “is a little different to making a movie in the US. If I was making 1000 Rupee Note in America, I would probably make it with 35 people.”

The film was released in India in 2014, and in the US two years later. Of making the switch from producing to directing, Sathe said, “I think having made two features before that as a producer really prepared me for what to expect; but it was nice using my left brain, right brain. I was the lead producer but I was also director so I was constantly having to do these checks and balances with myself to determine what was most important for the film, and how to safely do it, as well as maximize the creative intent with the financial resources.” Ek Hazarachi Note (1000 Rupee Note) went on to win the Special Jury Award and the Centenary Award for Best Film at the 2014 International Film Festival of India. The New York Times called it “harrowing” and “humorous.”

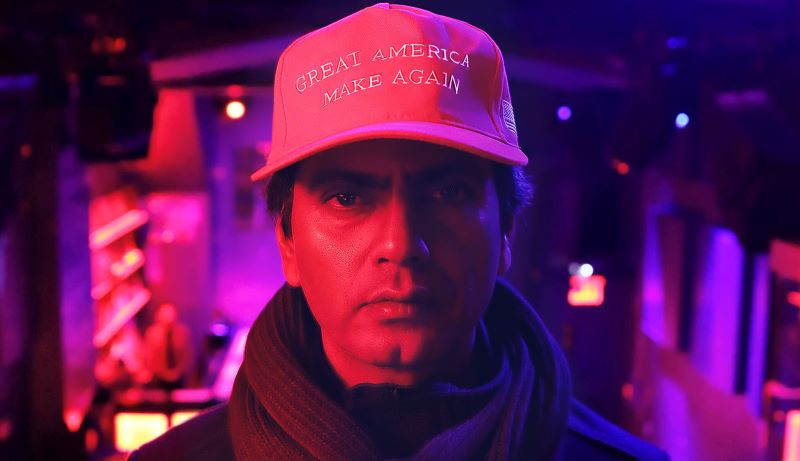

But while his debut came together quickly, Sathe reminded me that it’s not always the case. “Filmmaking is a pretty long journey," he said. "Sometimes it takes a couple of years to release a film, sometimes it takes ten years.” For instance, Sathe first met the director of his new film, No Land’s Man, ten years ago. He’d wanted to collaborate with Mostofa Farooki for some time. “Mostofa presented No Land’s Man to me in 2014. I liked the script but I didn’t think it was fully there yet so we kept in touch over the years and reconnected on the project in early 2019. By then, I felt the script had come a long way, and I came on board to produce the project with him. We shot in November 2019, in New York, followed by a shoot in India and Australia in February 2020, just before the global shutdown happened.” If they had shot any later the film might not have been completed. No Land’s Man, the tragic and strange story of a South Asian man’s odyssey to America, is an ambitious project. The film spans three continents and involves hundreds of extras. In many ways it’s a project that represents Sathe’s international taste and outlook as a producer. No Land's Man premiered at Busan International Film Festival last October, and stars the revered Indian actor Nawazuddin Siddiqui.

Our conversation turned to the future of independent film. What a time to be a filmmaker. Sathe said, “More people are consuming non-English language films. It’s not exponential, but it’s significant enough that more people are being exposed to different kinds of cinema, and that’s really exciting.” Having invested so much of his career in telling stories from across the globe—in their native languages—Sathe is pleased to see an increasing appetite for challenging, thoughtful, diverse filmmaking. As theaters reopen, and streaming platforms hasten to meet the rise in demand for new and international stories, now, he said, is as good a time as any to be working in independent cinema.

Shrihari Sathe is an Independent Spirit Award-winning producer. Sathe produced Jaron Henrie-McCrea’s Pervertigo, which world premiered at the 2012 Warsaw and Mumbai film festivals and was a part of the 2011 IFP Independent Filmmaker Labs. Sathe’s follow up production, Eliza Hittman’s It Felt Like Love, premiered at the 2013 Sundance Film Festival and the 2013 International Film Festival Rotterdam to great reviews. Sathe is a 2013 Sundance Institute Creative Producing Fellow and has received fellowships from the HFPA, PGA, IFP, Film Independent, and The Sundance Institute, to name a few. He is a Gotham Award nominee. Sathe is a Trans Atlantic Partners fellow (2013) and a Cannes Producer’s Network fellow (2014, 2015, 2016). He is a co-producer on Partho Sen-gupta’s Arunoday (Sunrise), which world premiered at the 2014 Busan International Film Festival, and Afia Nathaniel’s Dukhtar (Daughter), which world premiered at the 2014 Toronto International Film Festival and was Pakistan's Official Submission for Foreign Language Film at the 87th Academy Awards®. Sathe’s feature directorial debut – Ek Hazarachi Note (1000 Rupee Note) – won the Special Jury Award and the Centenary Award for Best Film at the 2014 International Film Festival of India and has received over 30 awards. Sathe produced Elisabeth Subrin’s A Woman, A Part, which world premiered at the 2016 International Film Festival Rotterdam. He co-produced Anthony Onah’s The Price, which world premiered at 2017 SXSW, and Eliza Hittman’s Beach Rats, a 2018 Sundance Film Festival winner. Sathe's production of Bassam Jarbawi’s Screwdriver (Mafak) had its world premiere at 2018 Giornate Degli Autori in Venice, and his production of Ritu Sarin & Tenzing Sonam’s The Sweet Requiem world premiered at the 2018 Toronto International Film Festival, where Screwdriver had its North American premiere. Sathe's production of Paul Felten and Joe DeNardo's Slow Machine had its North American premiere at the 2020 New York Film Festival. He has recently produced Jamie Sisley's Stay Awake and Francisca Alegría's The Cow Who Sang a Song into the Future. Sathe's production of Mostofa Farooki's No Land's Man world premiered at the 2021 Busan International Film Festival. In 2016, Sathe received the Cinereach Producer Award. He is an Adjunct Associate Professor and a Senior Production Advisor at Columbia University School of the Arts. Sathe is a member of the Producers Guild of America, Indian Motion Picture Producers Association, and the Academy of Motion Picture Arts and Sciences.

FEBRUARY 11, 2022

Producer Shrihari Sathe of New York-based production company Dialectic is enjoying the best time of his life, with no less than three of his projects, each completely different in style, genre and tone, being selected at A-list festivals.