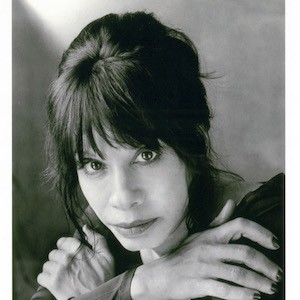

Soon After First Light: Binnie Kirshenbaum

Soon After First Light is a series where we talk craft, process, and pandemic with Columbia's accomplished writing professors.

Here, we talk with Professor Binnie Kirshenbaum '80 (CC) about the drafting process, mental illness, and saying what you think you shouldn't say.

Binnie Kirshenbaum received a BA from Columbia University and an MFA from Brooklyn College. She is the author of the story collection History on a Personal Note and seven novels, On Mermaid Avenue, A Disturbance in One Place, Pure Poetry, Hester Among The Ruins, An Almost Perfect Moment, The Scenic Route, and Rabbits for Food. Her novels have been chosen as Notable Books of the Year by The Chicago Tribune, NPR, Time, The San Francisco Chronicle and The Washington Post; she twice won Critics Choice Awards and was selected by Granta as one of the Best Young American novelists. She’s published short fiction and essays in many magazines and anthologies. Her work has been widely translated.

What is a typical workday like for you when you’re in the middle of a project?

Binnie Kirshenbaum: Well, when I'm waking up, it's late already (laughs). Usually when things are going smoothly, I will get up, make my coffee, sit down and write. Depending on the day and what else is going on, I'll do that sometimes just for an hour, sometimes for four hours. I find I can't go much more than that before I start to run dry. I mean, obviously if I'm teaching, I prepare for my classes. I read in the evenings. Lately I've been obsessed with the news and been spending a good part of my time on that. And I used to see people. I'm not one of those people who can do a lot of things. If you saw my apartment you would know that even taking out the garbage requires preparation.

I'm not somebody who's one of those uber-capable people who takes on a lot. I'm doing some work with student organizations, working with the Columbia Journal and putting together some small classes and things like that, but that's pretty much it. I'm also craftsy. When I was growing up, my mother had a rule that we could watch television provided we were doing something productive with our hands. So I still do that if I'm watching a movie or something, or even the news—I'm usually doing something with my hands. I do collage, a lot of collages. I think collaging is similar to putting together fiction in a way, or any writing where you have these pieces of things and then you need to try to arrange them in a way that is pleasing and it works, and you have to ask what goes with what and what should be on it and what shouldn't be on it. There’s a similarity there.

Do you think of yourself as a writer who sticks to a capital-R routine? Do routines help you “stick to” your work?

BK: I think the writing routine is really, really important. I liken it in a way to working out, or when you cut school and you don't go one day and then you don't go the next day and then the next thing you know, you've dropped the class or something. So I do think it's really important to stay connected, even if it's just a couple of sentences that you put down, or reading over what you did the day before and making a few changes. We have to look at it as a job because it is—and you go to your job every day, right? Obviously with the writing we can't always put in the kind of hours we might at a traditional job, but I think it's really necessary not to put it down for any length of time. I tell my students all the time and I try to live by this rule too: If there are days when you just have so much going on and you don't see where you can do it, grab 15 minutes. We can always find 15 minutes just to keep the thread going. So I think the continuity is really important

Have you ever had periods in your life where you feel like your daily life or your daily responsibilities are getting in the way of your writing? Did you ever have a moment where you had to make a change?

BK: Well, definitely. Some years back I was Chair of the Writing Program and I barely wrote at all, because that was two full time jobs; and I cried every day (laughs). I had some personal things with my husband and I had some other tragedies with friends who passed away. So those things obviously got in the way. Otherwise it is the priority in my life and I don't want to forget that ever.

What about experiencing periods of creative block?

BK: Yeah, sure. But I make something come. You know, I'm more than okay with saying I'm writing something for the garbage can, and I know it isn't going to amount to much or at least I don't think it will. And sometimes when [a creative block] happens, I'll just sit there and write about why I'm having a hard time writing, what's going on, what's in the way; but to sit there at the desk and to put something down on paper, I just think is really critical.

In an interview for Guernica's “Miscellaneous Files,” you said that you often tell students "revision is the writing." Could you talk about this? What is your advice for young writers who may find the editing process daunting or difficult?

BK: Every writer has a different way of doing things. I know writers who will not go on to the next sentence until the sentence prior is exactly the way they want it. I wouldn't get any momentum if I did that, I would stay with one sentence for a month. So, what I do is I write a first draft as quickly as I can. I find the blank page the most intimidating thing. When I start writing, I have a starting point, although it doesn't necessarily wind up being the starting point [in the final draft], and often I'll have an end point or a vague idea of an end point. The journey just comes as I go along. And so I put out this first draft as quickly as I can do it, just to get over the anxiety of getting something onto paper and also to give me an idea, although how I’m getting there changes from draft to draft. So once I do that, I mean, it's total garbage. I would never show it to anybody in a million years (laughs).

But when I print that out and read it over, I get a better idea. I do a lot of marginalia then, and a lot of note-taking as well. When I start the second draft, I have a much better idea of what I need to do. I use the first draft as an outline. So I keep it on one side of the desk and I refer to it, but I find that it's inside me usually well enough that I only have to refer to it occasionally. I refer particularly to the marginalia. I will look at what my problems were. Then when I print out the second draft, I do the same thing and read it over and see what's missing and or what I don't need. Then the fifth or sixth draft, that's when I do what is my favorite thing to do, which is really cleaning up sentences. It's completely free of anxiety and I see immediate results. It's like polishing silver and I see the shine come out. I really enjoy that part. One of the more exciting things for me, when I go from draft to draft that way, is how much changes.

I think it's because each time with each draft, I get to know the characters better. So there's more revelation about them. In getting to know them better, I see what's lacking in the story. And so I look at it sort of like meeting somebody and chatting with them, and then the next time I meet with them, I have lunch with them. Then the next time it's a long dinner, and then we go away for a weekend and then we live together (laughs). Depending on how that goes, I've written books that took me two years and then this last one took me 10 years. So the average time for me to write one was four years. I found as the drafts went on, it got easier, I got more comfortable in it. And so I didn't struggle quite as much.

Do you have a sense of why Rabbits for Food (Soho Press, 2019) may have taken you so much longer than your other novels?

BK: It was a combination of a lot of things. I had a very hard time finding the form for this novel. I felt that I needed to get the character's past in there because it was important to where she is when she breaks down and why she breaks down, but I didn't want to start in her childhood and work all the way up. I was doing far too much backstory and far too much flashback and it was dragging on and I just didn't want that. I wanted it in a very contained period of time; and so I thought, well, let me just try it. I first tried it over a week, the period between Christmas and New Year. Then I decided I didn't want that. And then it just sort of hit me that I wanted [the events of the book] to be just one day and I could work in what was necessary about her backstory and thread it through. When I did that I thought, Oh, that's working, maybe I'll do the second half the same way; but when I tried to do that, it wasn't working. So I decided to just let that go and write it in a more traditional way, spread it out over however much time it needed. What I find is that after a while the form starts to suit what’s required of it. It actually took me a couple of years just trying different forms again and again, and having it just not work; but once I realized what the form needed to be, it went much faster.

Did you ever have a moment where you thought you needed to give up on the novel?

BK: Oh yeah.

What stopped you?

BK: I actually wrote a novel some years back that I finished and threw away. I had a friend who was my reader—I think every writer has to have their reader, and I tell my students before you leave Columbia, make sure you have a writing buddy. You really can't write in a vacuum. Somebody has to be either looking at it or talking it over with you. And it has to be somebody who's going to tell you the truth. My reader always told me the truth. When I finished that novel, I said I just can't breathe life into this thing; and she said, you talked about that book as if you were talking about your geometry homework (laughs). I said, you’re right and threw the book away.

The other thing I used to do was I would get to a point—I think this happens with every book I've written—where I think, this isn't working. I would have another idea that would seem like the thing I want to really be writing. I would tell [my reader] and she would say, you say that every time. She was wonderfully honest, and she was right. I would get to a point where I would just feel tired of it. You can liken it to taking your favorite book in the world—how many times can you reread it? How many days in a row, how many years in a row, can you read that same book and not feel tired? So the same thing happens with your own work, but I would make myself get back to it. Because I knew this was something I did want to write. I was just sort of getting that fatigue with it that will last a little while and I would get back to it and then the adrenaline would start again.

With Guernica, you also spoke about one of your "rules" for writing—"if you think you shouldn't say something, say it." Can you speak about this practice and how it might affect your writing process?

BK: It's a very difficult thing to do in two ways. One is that you don't want to present yourself in a certain light, even though your character is not you. If you're writing fiction, your character is never you, even if it's based on your own experience. But I think a lot of people have this desire to present themselves in a certain light, which is not a true light. It's one of the problems I find with memoirs often, right? That the person who's writing them wants to come off as the perfect being with all these other monsters around them—and that's dishonest. Other people fear what people are going to think. I know a lot of students have a problem writing things based on families or friends because they don't want to hurt that person's feelings. And then there's just things that are unpopular or, you know, ugly or vulgar or whatever. Often there's that desire to write this and then your conscience kicks in.

I think writing to hurt somebody as a motivation is terrible. I don't think anybody should ever do that. But when you are writing something and you do need to be honest and say something ugly about a character based on your father, it's really important to break through your own sense of shame. There's always something that we've done that we really can't tell anybody, or something that was done to us. What's really important for writers is to write that down. Tear it up when you're done, don't show it to anyone; but the fact that you wrote it down on paper helps. People have to understand—and they don't always—that you have to be true to yourself as a writer.

My husband never read anything I wrote. He just wasn't interested in fiction. And it was a relief, I realized, because I didn't have to worry about whether something I wrote would hurt his feelings. if I wrote this about a husband, or if I portrayed somebody's husband in this way how would he feel? As it turned out, he was really great about all of it. His main concern was I do what I wanted to be doing. I found it rather liberating.

You've written about mental illness and have spoken openly about your own struggles with depression. What advice do you have for young writers who feel that their writing is being affected by mental illness?

BK: I had these long bouts of depression at about 16 or 17, and I kind of chalked them up to well I'm a teenager, I'm living at home, I'm miserable, I don't have any friends. Then I realized that they continued and I think I was afraid to do anything about it because I thought that it would interfere with my writing—that being depressed was important to me as a writer. It finally got really, really, really bad. I just couldn't take it anymore. And although I've been on a gazillion antidepressants of various sorts over the course of my life, the first time I tried them, I made this bizarre discovery that not only did I write more and the writing was better, but I was able as a writer to go to dark places that I was afraid to go to when I was depressed. So it actually made the work more depressing, (laughs) even though I was not as depressed. I couldn’t go there when I was depressed, it was too hard. So my work tended to be lighter and in some ways maybe more frivolous. You asked actually before about whether there were periods when I didn't write. When I was depressed I would write, but I realized that everything I was writing was not good. And then that would make me more depressed. I would sit there at my desk, forcing myself and staying there all day long, writing something that didn't have life in it. Because I didn't have life in me. And so alleviating the depression became very important, not just for myself and the people who cared about me or lived with me, but for my work.

Although the character in Rabbits for Food shares a lot of experiences that I had, she is not me. The reason she has the name Bunny, which is one of the reasons everybody always thinks for sure it’s me, is that I initially had started the novel with a very different idea as to how I was going to write it. I was going to do it as a metafictional kind of thing. Then I decided that was silly and it wasn't going to happen, but I'd already named her Bunny and it stuck. I kept thinking, well, I'll change it; and then as I went along, I thought I can't change it, it's just who she is. So I left it, knowing that people were going to assume she is me, and I realized I didn't care.

After the last breakdown that I had, I realized that keeping this a secret was contributing to the stigma against mental illness. I felt it was really important to be upfront about it and to have it be no different than any other sickness I might've had. People should not have to feel ashamed of it or embarrassed or feel like it's something you have to hide away or you can't tell anybody.

How have the pandemic lockdowns affected your creativity (for better or worse)?

BK: I had started something before the pandemic and I was on sabbatical last semester when the pandemic started and everybody got sent home. I already had been at home by myself, though I could still see people in the evenings. So I was already writing during the day and I was fairly well into something. The pandemic didn't affect that because the story that I want to tell and the characters I want to write about, they've already inhabited me. The problem I've had is writing as much as time is actually allowing for. I am definitely writing less. And I can't figure out why that is. I think part of it is I do have to deal with email and I think in the pandemic, I'm getting a lot more of it.

I do find that I will spend what might have otherwise been writing time answering emails. I'll write and then I'll look at the clock and think, there's three emails waiting that I absolutely have to answer now, and I'll start to do them. Then there'll be a whole bunch more that I actually have to answer now. And then I think, well, why don't I just get these other ones off my plate so that I'll have more time to write tomorrow? But it's a never-ending cycle.

Which non-writing-related aspect of your life would you say most influences your writing?

BK: Before, when we could go out, I always used to go to flea markets and I would find things inspiring because I would think about who had this before it wound up in a flea market and how did it wind up in a flea market? I started to collect found photography and I started to accumulate these stacks of photographs.

It was a friend's birthday, and I realized I didn't have a card. So I took a photograph and I cut out and put a birthday hat on it and made it a birthday card. Then, for the next birthday, I did the same thing, but got a little more elaborate with it. My interest in collages came from those and in the book I'm writing now, I actually made the woman a collage artist because she is trying to put pieces of her life that are coming undone back together.

I suppose I get a little inspiration sometimes from the photos, just wondering about other people's lives. Things like that will sort of prompt the wheels. I think getting the wheels turning, to start thinking about people outside of oneself, is important.

What are you working on now and what’s next?

BK: I'm writing what I thought was going to be a novella, and the first draft came out longer than a novella would be, which is rare because usually the first drafts are much shorter than the novel winds up being. I said something to my editor about it, and he said, I was thinking that this should be a novel. So I'm rethinking that. I'm writing it in short chapters, which I like a lot. I did that with Rabbits for Food. I've done it with other books too, but in this one they're very deliberately short, and they're all one scene. I wanted to look at them as a photograph album and explore in that way a character who is losing his memory.

What advice would you give to artists who are just starting to figure out Process and Routine?

BK: I would say, look at your schedule and be honest. Don't say you're going to get up at four in the morning and write for three hours because you're not—but find a slot of time, 15 minutes, a half hour, an hour, two hours, if you can. Now the temptation happens when your friends call, like if you find some free time around dinner time, then your friends call and say, Oh, you want to go out for a drink? What you have to learn to say is I'm working now, but if you're still going to be there in two hours, I'll come join you. Like I said before, it's a job and you have to adhere to it. But be honest.