This Is Who We Are: João Pina

This Is Who We Are is a series featuring Columbia School of the Arts’ professors, covering careers, pedagogy, and art-making. Here, we talk with Visual Arts Lecturer João Pina about his career as a photographer, his new project, Tarrafal, and why failure is essential to learning.

Professor João Pina and I met in Joe's Coffee, inside the building designed by renowned architect José Rafael Moneo. Pina was still a bit lost on campus, having arrived in New York less than two months ago to teach an archive photography class at Columbia University School of the Arts. However, when we started talking about photography, his eyes immediately gleamed, putting him at ease as if he had been here for years.

“There are some things in life that you decide and others you don’t. Photography chose me,” Pina said right off the bat. “Because I can't write, because I can't sing, because I can't paint, I was left with this tool, which is magnificent, and decided to be a photographer,” he said, gesticulating as if he were manipulating an imaginary camera.

Pina remembered the first time he took a picture in his life. He was only four. “My grandfather had a camera that you had to look into from the top, a TLR camera, where the left would be on the right and the right on the left. I remember [training] the camera on my younger sister, who was learning how to walk. I clicked, and nothing happened because it was very silent. 'That’s it!' I always remember that sensation,” he said.

Born in Lisbon, Pina started working as a freelancer for a music magazine and then interned for a newspaper in Porto, where he learned the ropes of photography. The defining moment in Pina’s early career, however, came in 2002 when he truly cut his teeth during the coverage of the Prestige oil spill off the coast of Galicia (Spain). He was barely 22 years old, but he hung out with world-class photographers.

“I spent days talking, learning and asking questions to photographers from Newsweek, Magnum Photos, etc.,” Pina said. “Being with them helped me to understand what I wanted to do and how I wanted to tell my stories. I also realized I was too young to stop studying.”

Months later, at 23, Pina was accepted into the prestigious International Center of Photography in New York, founded by Robert Capa’s brother. Pina was a man of action, though, and he couldn’t help but think about his great passion: Latin America. “During the winter, I remember thinking: what am I doing here? This internal conflict was fascinating because I was learning a lot, but I wanted to go out there and work. When I finished [at] the ICP, I knew which type of work I wanted to do as a photographer. Before coming [to the Center], I knew how to operate a camera, but they helped me learn how to think and see beyond the technical aspects.”

Like other photojournalists, Pina was interested most in conflict, post-conflict and human-rights violations issues. Over most of his career, he's been based in Latin America, bouncing around different places like Brazil, Cuba and Argentina. After the ICP, he started working on his most ambitious project: Condor. The project is a nine-year research story documenting the remnants of Operation Condor, a large-scale secret military operation to eliminate political opposition to the military dictatorships in South America during the 1970s. He published a book in 2014 called Condor (Blume, 2014).

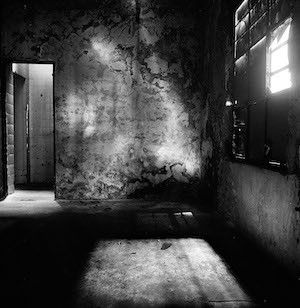

"I started researching for my project, Condor, and asking the questions that helped me comprehend my photography. How can you tell the story of someone who has disappeared? The moment when you grab a camera, you already have those questions in your head. Photography, for me, is raising more questions than giving solutions. I don't want to give the viewer an answer. Thousands of people disappeared in Argentina during the fascist dictatorship. What do I do? I take a photo of a corner of one room. And then you read about what that corner means from a victim's perspective."

Pina has worked extensively for prestigious international media outlets such as The New York Times, Newsweek and El País. Still, he’s more interested in publishing books, curating exhibitions, and collaborating with institutions, partly because working for a newspaper in a certain way is no longer viable; but also because nowadays everyone is a photographer.

“The moment that we’re living in photography is the equivalent of the invention of the pen,” he said. “Everybody can have a pen. But one thing is to have a pen; another is to write good literature. Everybody thinks they can be a photographer. But one thing is to make photographs; another is to make something with those images. Interpretation. Poetry. Movement.”

At one point in the interview, I asked Pina what his technique was to engage with the people he photographed. "It's easy! It's a social skill. I spend a lot of time talking, and I spend a lot of time listening," he said. To make his point clear, he made me his interviewee. "I'm also very interested in portraits. If I want to photograph you, we go to a place relevant to your story, and we talk, and without knowing it, you're already telling me your story, I'm picturing it. I know what I must do If I want to take a portrait of you. I'm studying you as I'm speaking to you."

"Everybody thinks they can be a photographer. But one thing is to make photographs; another is to make something with those images. Interpretation. Poetry. Movement.”

Pina's new project is related to his family. This time, he's trying to answer the question of how one deals with historical events from a personal perspective. He's focusing on one village on a tiny island in one small country: Tarrafal. Close to this town there was a concentration camp where his grandfather, alongside other political prisoners, was imprisoned during the Portuguese fascist dictatorship. The book and an accompanying exhibition will aim to provide a personal visual record of the colonial and political history of his native Portugal.

"My grandfather's parents went to visit him in Tarrafal. They were the only civilians authorized to do it. They brought their camera and photographed all the living prisoners and graves. Upon returning to Portugal, they delivered the prisoners' photographs to their families and took photographs of the families to send back. I opened this Pandora's box three years ago, and I've been working with these materials and doing my own pictures," he said. The concentration camp was closed in 1954 for Portuguese political prisoners but reopened in 1962 when the Colonial War started. "African political prisoners were also sent to the islands. There's the whole African aspect to it and the anti-colonial fight."

It is the first time that Pina, who’s teaching an Archive Photography class this fall, has constructed a whole syllabus from scratch, but Pina is thrilled for the challenge. "I've divided the course into three types of archives: family, public, and anonymous. There's a fourth one: the archive of the future, what we're producing now," he said. "This Sunday, we're going to the flea market to find anonymous archives. Next week, we're going to the New York Public Library to study their print collection," he said. "I want to push my students. It's all about making them think visually and decide visually."

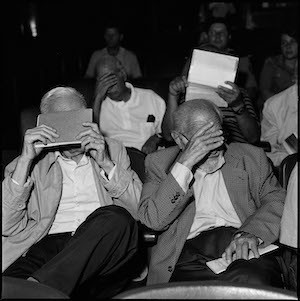

As our interview drew to a close, Pina defended failure as a learning process. For him, failing is a refreshing inner challenge. Sometimes, he said, a fiasco in the past makes perfect sense in the future. "I was photographing trials for crimes against humanity in Argentina. Photographically speaking, I treated the criminals the same way I treated the victims. I was not at ease with that. I came up with this idea that I rarely use: the use of a non-natural source of light. I decided to go to the courtrooms and use the flash on my camera. Thanks to my previous failure, I discovered a new perspective to differentiate between victims and perpetrators. You must ask those questions in advance to determine the outcome."

João Pina is a freelance photographer born in Portugal in 1980. He began working as a professional photographer at age eighteen and graduated from the International Center of Photography’s Photojournalism and Documentary Photography program in New York in 2005. His work has been exhibited at the Open Society Foundations (New York), International Center of Photography (New York), Point of View Gallery (New York), Howard Greenberg Gallery (New York), King Juan Carlos Center–NYU (New York), Canon Gallery (Tokyo), Museu de Arte Moderna (Rio de Janeiro), Museo de Arte do Rio (Rio de Janeiro), Paço das Artes (São Paulo), Centro de Fotografia (Montevideo), Museo de la Memoria y los Derechos Humanos (Santiago de Chile), Parque de la Memoria (Buenos Aires), Torreão Poente – Museu de Lisboa (Lisbon), KGaleria (Lisbon), the Portuguese Center of Photography (Porto), Visa pour L’Image (Perpignan), and Reencontres d’Arles (Arles). He has published three books: Por Teu Livre Pensamento (2007), Condor (2014) and 46750 (2018). In 2017, Pina was also a Nieman Fellow at Harvard University. In 2020 he was an Abigail R. Cohen Fellow at the Institute for Ideas and Imagination at the Columbia University Global Center in Paris, France.