Conversations with Artists in Art Getting Art: Kiyomi Quinn Taylor '20

Conversations with Artists in Art Getting Art is a bi-weekly series and a play on Jerry Seinfeld's Comedians in Cars Getting Coffee. We interview artists about their art and 'getting art'.

Kiyomi Quinn Taylor’s '20 interest in dinosaurs is a natural extension of her interest in family histories and the totally unstoppable nature of the future. She has incorporated dinosaurs in her work in a variety of ways. For instance, during Open Studios, Taylor constructed dinosaur masks and hung them from the ceiling. She and a couple of friends then improvised a musical performance for three hours, with Taylor singing. Her voice is jazzy, sweet, haunting. Her mother is also a singer; on weekends Taylor sings in her mother’s band based in New Jersey.

“I think of dinosaurs as a metaphor for learning to live with things from the past that will never go away,” says Taylor. “Especially when our generation talks about the destruction of the earth, it makes me feel better that if we fuck up so much that the human race is wiped off the earth, things will keep on rolling, something else will come up, it doesn’t matter to me what.”

In this conversation, Taylor and I talk about dinosaurs, novels, and the freedom one finds to create art.

Professor Dana Deguilio taught at NYU, where you went, and now teaches at Columbia. I remember you’d told me before that what you liked about her was the way she described painting. How did she describe it?

KQT: She was just so excited about painting and often talks about it—she’s really a poet. I don’t want to say she has a simpler view of painting, but she has a very emotional view of painting, she often talks about how the way that you touch something is incredibly evocative of the mark you make. It’s hard to say—the content being reflective of the way you interact with the object. She’s really about the relationship of the person to the painting and the way that relationship is fraught and intense, but mostly how that relationship does come through in the painting, in elements of the painting. You touch the paintings, and in what you put there, what you choose to leave out of the painting, is there in every way.

Would you say her interpretation of painting is that the medium always matches the painter’s message? Like there is no way to hide in painting, like there is in movies, text, or music.

KQT: It’s her belief that what you put there is exactly what the painter will exude. And how you put it.

How do you go about placing images on a canvas?

KQT: I guess, anxiously? And with a lot of layering (laughs).

I see a lot of fabrics around your studio.

KQT: Yeah, I’m getting into fabrics because I really like textiles, I’ve always liked textiles. I grew up with these old kimonos—my mom is half-Japanese, and she was born in Japan. My grandmother is Japanese. I just really like texture, and textiles, and I think for a long time I kept trying to get that texture with paper, in painting, and then I realized if I mixed all these things together (paper, fabric, painting), then I was getting somewhat closer to what I actually wanted.

I also find fabrics really durable, and obviously flexible. I like that you can hang it around anything, any structure. You can hang it from the ceiling, you can spread it over something, you can drape it. It’s versatile, it’s flexible, it’s pretty. I feel like I’ve collected a lot of fabrics, a lot of which I don’t know when I’m ever going to use, but I’m addicted to buying fabrics.

What are you working on right now? Does it involve fabrics?

KQT: I’ve always wanted to make one actual, true painting since I’ve been in grad school. I had a bunch of crazy ideas I wanted to try out. Sewing stuff into fabric, printmaking, performing. For Open Studios I sing, so I made these moving dinosaur masks and I hung them from the ceiling, and for the whole three hours we just improvised music from behind our masks. They were designed to correlate with whatever we were doing. So vocalists’ masks, their mouths moved. My friend Hannah plays the clarinet, so she has a slit in the mouth that she can put the clarinet through. Performing, moving masks, I made these big sort of fu dogs, but made them in the image of childhood dogs, family dogs. Making big stage sets, basically. I was thinking about them as stage sets to facilitate a performance, to perform around. I’ve been doing that since I’ve been in school.

I actually had a kind of complicated thesis idea that wasn’t this. I was going to continue my performance, the moving diorama thing. This is the sort of thing we were making for three hours. We were behind the masks the entire time. But now, I’m trying to bring all the stuff I did into a big painting which I’m now making for my thesis.

What were you going to do?

KQT: A water-powered diorama that moved. I was going to build a little water wheel and put it in the path of a fountain, and that would be hooked up to a mouth on a hinge, sort of like these dinosaur masks. The image was going to be of me, hugging this giant heron in front of the ocean. There would be two backgrounds in the diorama, I would sing with my mother, but Lenfest—they don’t allow water! They have this stupid expensive bamboo floor. So I decided I’d work on this big painting instead.

I also make a lot of cut-outs for functionality, so I’m trying to treat my big painting like I treat my little cut-outs, as stop motion animation sets, almost as if I have to move them. I’m trying to treat this the same way. This is also the biggest thing I’ve ever made, for sure.

Tell me about your thesis painting. It’s a rather large painting—these are investments of time, resources, expenses. It must take a certain level of freedom to undertake such a big painting, or certainty. How do you feel free?

KQT: I feel really scared in other aspects of my life, so I felt in my practice of making art it’s super easy to be the person I want to be because this brings me back to my teacher—I think I sort of failed to put this in the right words earlier. Dana just has an immense faith in painting as a medium for being able to hold a lot of things. For being able to hold whatever you want it to hold. I feel in my studio when I’m making work, I’m really impulsive. I never use pencil.

Part of making work for me is being the fearless, impulsive person who just does it. I often feel like I’m not, in my personal life. In this space I can be the person I want to be, someone who just does it. I’m never really nervous because I know that things are additive. Like if it doesn’t work, you take it out, paint over it. For me, the stakes are really high, because I want things to be good, but if I keep working on it, it will eventually be good, as in I’ll like it eventually. (Laughs). When I make work, I take a lot of solace in knowing that by some massive investment of time or energy, I can make it work.

Is this something you realized over time, or with a certain project?

KQT: I think I’ve always worked like this—since high school, I just dive into things without thinking about it too much. It’s definitely something I’ve learned more about as I went through undergrad, and then came into grad school for sure. I think about it a lot more now, the freedom I allow myself. Now, I’m trying to take a note from my art self in my personal life.

A lot of my painting is about self-haunting. Inner conflict, self-conflict. I feel like I’m always fighting myself on things. I myself always feel personally conflicted. I feel like I have a lot of voices in my head. I’ve recently given myself an alter ego, Stellaluna, a personification of a voice. She’s like a demon, in that kabuki fashion, but I don’t think of her as bad, just animalistic, or natural. This painting is about inner conflict, fighting yourself on things, those clashes that happen internally before I make any sort of decision about my life. I’d say this sort of self-haunting inner conflict that takes place before you make a decision to change. I think it’s about change in a lot of ways. Whether it’s to go to school, to start a new job, break up with someone, to enter a relationship—this sort of inner turbulence about whether or not you should change your life in that way, not knowing if it’s the right decision.

What was growing up like for you?

KQT: I’m from New Jersey. I grew up in a commuting town that’s only half an hour away from New York, via Penn Station. I’m home a lot (laughs). Because I sing background in my mom’s band, which is crazy. It’s like a soul-funk cover band. They just started writing originals though, which is cool. I grew up in New Jersey, in a really diverse suburb, Mapso we call it: Maplewood and South Orange. We shared a high school. I specifically grew up in South Orange. I went to Columbia High School. It’s just a really creative place because it’s a commuter town, most of our parents lived in Brooklyn during their twenties, met each other, married, got kids, and then moved to a nearby suburb where they could have a yard but still commute to their New York job. So a lot of my parents’ friends were creatives, worked on Broadway, were dancers. My parents never had creative jobs, but are creative people. My mom was making collages when I was younger, which now when I think about it, was overwhelmingly impactful to how and why I make work. She’d just use anything. She’d pick ferns and lay them down on the canvas, spray paint over them. My parents were musicians. My mom sings, she used to sing in local bands, but also she and my dad released an R&B album together in the 90s, my dad plays the keyboard and she sings, it’s on Spotify. I don’t know why it’s on Spotify.

I grew up around creative people, my older brother is a writer. He has been very impactful in my life, a voracious reader of sci-fi and fantasy when we were younger. He would wake me up in the middle of the night when I was thirteen and say, “Read this short story I wrote.” And he asked me to edit it… so he surrounded me with a lot of storytelling and I feel like a lot of my work is about storytelling. I always feel like I’m composing these scenes the way my brother composes scenes when he writes short stories. I grew up around a lot of family and friends who were creative in different ways, and that has had a huge impact on me. I feel really lucky to have had all those particular influences. I would view all these things as connected, and I think a lot of people give me a lot of credit for doing a lot of different kinds of things, but that’s just how I think about work. I’m always trying to tell some kind of story whether I’m singing, making stop animations, painting, and I think that’s a testament to my family and the people I grew up around.

Why do you think storytelling is so important in creating visual art?

KQT: To me, it’s the part that’s exciting. The only thing that excites me is storytelling. I really like to read, but I love drama, the drama of a story, a well-told story with character to care about. There’s nothing better. Stories are also how we understand people and understand ourselves.

I read a lot of sci-fi, gothic horror. I like H.P. Lovecraft, which is funny. Arthur Muckxhin. I’m reading a Phillip Roth novel right now.

All fictional.

KQT: Everything is fiction, I never read nonfiction (laughs). Honestly the only nonfiction I’m into, I’ve always been into my family’s oral history. Those stories get me excited too. Also earth history. Like my grandmother was a wealthy shipping magnate in Japan for cocoa, and she met my grandfather, who’s black, from Arkansas, at a military base. They got married, and her father disowned her. She went from being really wealthy to cleaning other people’s houses in Washington. She used to swim two miles out into the ocean every morning. She’s a really strong swimmer. She would tell this story about when a large turtle swam over her head while she was swimming and she almost drowned because she couldn’t get up for air. My grandfather, likely bipolar, an alcoholic, depressed, wrote reams and reams of depressive poetry that he never shared with anyone. These stories of intense personalities, and fate, negative turns of fate that lead somehow to a variety of other things, the life of my mom, the lives of me and my brother. I make a lot of work about my grandmother, my grandfather, on both sides. My father’s parents met at fifteen in a roller skating rink in New Jersey, and were in an on-and-off relationship for the next forty years. My grandfather owned a bar called the Royale in upstate New York, would get into bar fights, and he was hit by a drunk driver in the winter… I just think the strangeness of reality is really interesting, especially—I’m biased, because those are my own family’s stories, but I think about that—irony, tragicomedy, foreshadowing. I think about how these aren’t just literary elements but true elements of some sort of inner life.

And that’s why fiction is really important to me, because even though it’s fictional, these tenants of high fantasy novels, the idea that the world is usually cyclical, like in gothic horror, curses, blood curses passed down, exist in life. I think in my family of mental health, heart disease.

Do you think about your future a lot?

KQT: I’m generally afraid of the future. It’s not good for us. I don’t know what my future is going to look like.

I really enjoyed what you said earlier about fiction, and how we learn from fiction. What do you think about learning from nonfiction writing?

KQT: I hate nonfiction so much unless it’s science (laughs). I’m really into dinosaurs.

Could you talk about this dinosaur interest a bit more?

KQT: It’s kind of like what I’d said earlier—I’m really fixated on the stories of the past. We still sort of live with those people and the things they lived with, whether in literal ways, like mental health passed on, physiological things passed on genetically. So I think of dinosaurs as a metaphor for learning to live with things from the past that will never go away. I also find dinosaurs kind of reassuring, because we came after dinosaurs. So when I think about the idea of extinction on a personal level as well as a macro level, there’s no cataclysm that can completely stop the development of creatures, time, other things from happening, other life from transpiring. In that way I find that reassuring.

Especially when our generation talks about the destruction of the earth, it makes me feel better that if we fuck up so much that the human race is wiped off the earth, things will keep on rolling, something else will come up, it doesn’t matter to me what.

I love these images of windows in your studio [right]. Is that a human figure standing “outside?”

KQT: That’s from a photo of my dad when he was a little boy, digging a hole in his backyard. I’m lucky enough that my family has an extensive archive, like a lot of photos from Japan from the 40s and 50s, and from upstate New York in the 50s, 60s, 70s. There’s been a lot of untimely deaths in my family, like my dad’s brother, both of his parents, my mom’s dad—I didn’t really know any of my grandparents except for my grandmother. In that way, those stories are not fiction, but I’m fixated on them because I don’t know these people but I have the pictures and I have the stories and I think I’ve been able to project a lot onto them as narrative. To me they are almost purely mythological characters because I didn’t know them, and I have images and really dramatic stories and that’s it. And that somehow led to me and my brother.

[Right: 'TitesWindow' by Kiyomi Quinn Taylor '20, image courtesy of the artist.]

What went behind the decision to put the windowpane in front of your dad? Was there a windowpane in the photograph? Was this photo taken through a window?

KQT: I wanted to more actively create a space of fiction—well, not fiction, but time travel. I wanted to somehow make it so that the space itself was activated to time travel by creating a window to something that has already happened. Hopefully it looks like it’s happening now because there is a window, you know, a very normal feature that you can look through. That was my hope.

What classes have you liked at Columbia so far?

KQT: I really liked Lizzy DeVita’s Writing for Artists class, she taught that last semester. I was really bad, I haven’t taken any classes outside the school of the arts.

Tyler Coburn teaches genealogy of time, or methodologies of time, or methodologies: genealogy of time. A lot of good readings, good discussions. Print into Drawing, printmaking, I took that class the first semester—they teach you how to make books. That’s where I developed this whole thing [above]—it would not have occured to me to poke holes in a painting and sew something in. That class was formative for me. Taught by Tomas Vu-Daniel.

Who are some of your creative inspirations?

KQT: I like H.P. Lovecraft. He was a mega-racist, famously so, but even that’s very interesting to me. He would have actual chronic night terrors, which is why he wrote all these horror stories in the first place, but I think the link between fiction and actual fears, whether or not grounded, the link between imagined fears and real fears—I find H.P. Lovecraft fascinating. His short stories, and the fact that they’re complicated by the reality that he was racist and had all these unwarranted fears. That, to me, makes it more interesting.

I always like classical Gauguin paintings. His use of color is so lush. I feel like all the people I like are problematic. I really like Wangechi Mutu as well, she’s young and alive (laughs). Mequitta Ahuja. Those are two visual artists I really like and respect.

I feel motivated by books, mostly, and also by—honestly, I watch a sickening amount of reality TV. The narratives the producers are making, but also the drama of ordinary people, it’s like a weird mix of true lives, and their manipulations into fanciful, televised dramas. I just think the tragedy of real lives is really interesting—that’s funny. I like characters, imagined or not. I mean it’s interesting because on TV, people are real, but imagined in the way that producers are manipulating your story, editing it. Robert Jordan’s The Wheel of Time series. It’s a famous high fantasy series, akin to Lord of the Rings, but better, I would say.

Image Carousel with 3 slides

A carousel is a rotating set of images. Use the previous and next buttons to change the displayed slide

-

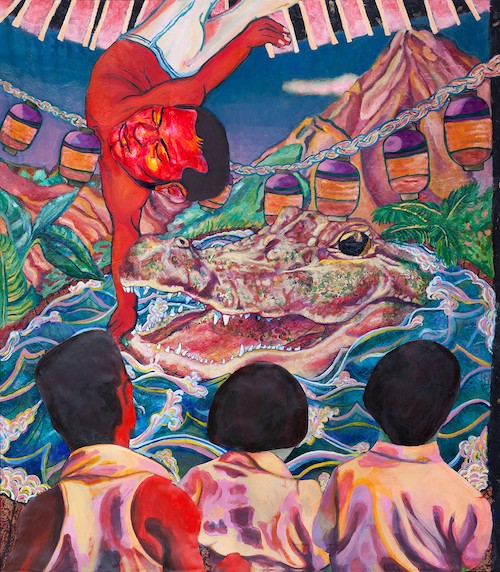

Slide 1: Alligator' by Kiyomi Quinn Taylor '20, image courtesy of the artist. Read more from this series

-

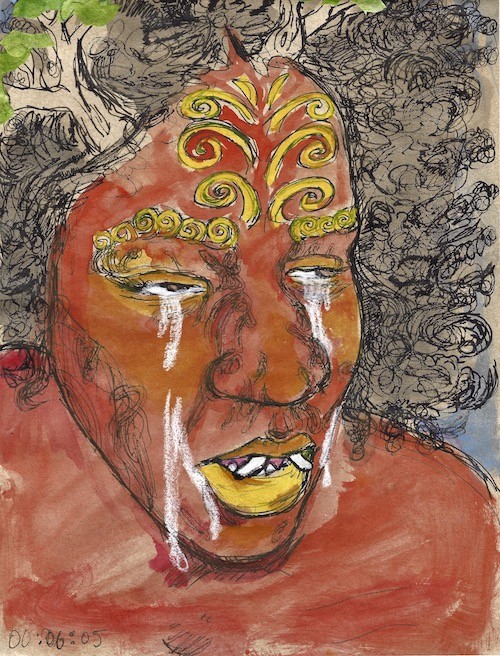

Slide 2: 'Animation' by Kiyomi Quinn Taylor '20, image courtesy of the artist.

-

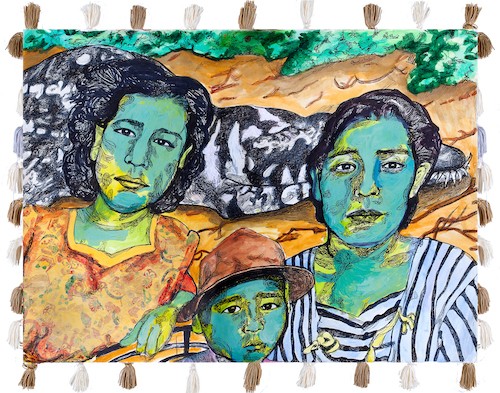

Slide 3: 'Liopleurodon' by Kiyomi Quinn Taylor '20, image courtesy of the artist.

Alligator' by Kiyomi Quinn Taylor '20, image courtesy of the artist. Read more from this series

'Animation' by Kiyomi Quinn Taylor '20, image courtesy of the artist.

'Liopleurodon' by Kiyomi Quinn Taylor '20, image courtesy of the artist.