Constructing Futures: Making Ecological Art in an Age of Uncertainty with Student Kelsey Shwetz

Constructing Futures is a biweekly series that features artists who use found materials, natural resources and the landscape to construct work that addresses the harsh realities of our ecological age.

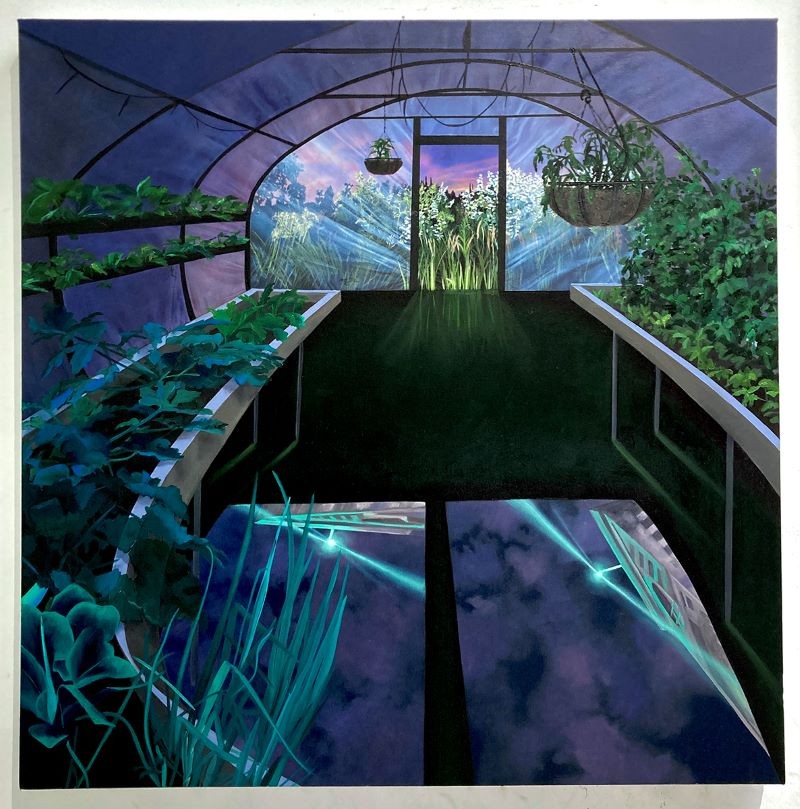

Student Kelsey Shwetz is a painter working in the space between realism and the uncanny. Her canvases feature spaces that dramatize the inability to separate the manmade and the natural such as the greenhouse or the suburban backyard. With eerily oversaturated colors and shadows cast by unseen plants, the paintings place the viewer on guard, shrinking the space between a conventional day to day and imminent climate catastrophe.

Shwetz is a Canadian-born painter now based in New York. She has been a visiting artist at Pratt Institute and Laguardia Community College. She is the recipient of the Edward Mazzella Scholarship, the Ellen Gelman Fellowship, and the Three Arts Club Scholarship. She was awarded fellowships at the Vermont Studio Center and CanSerrat Residency in Barcelona, and grants from Canada Council for the Arts, The Elizabeth Greenshields Foundation, and the Mayer Foundation. Her most recent solo exhibition was at Casa Equis in Mexico City in April 2021.

Walking into Shwetz’s studio, I found her seated on the ground, painting the bottom of a large canvas. She hopped up to make coffee and I looked around at the big windows throwing light onto fake plastic plants. When she returned, she read me a parable in four parts that imagined different visions of the climate. This writing emerged from a collaboration with artists at the Vermont Studio Center. Each of her current paintings corresponds to a different section of the writing, highlighting the importance of working with artists of various disciplines, especially during the isolation of the last 18 months.

Looking through your paintings, especially recent ones, there's a lack of human figures, but as you say, we're living in an age of human induced climate change. Where does your work fall in these questions and what are you doing with the lack of the human figure in your pieces?

KS: I used to be a figurative painter and then I slowly started shifting to spaces that have the presence of a human involvement without actually picturing the body. So I'm really interested in how I can indicate through painting or through the use of light or reflections or objects, ways to indicate human presence while maintaining the absence of the figure. So in a sense, the viewer becomes the figure in the space. The only figure in the space.

I think the impulse for that comes from my thinking about the Group of Seven who were a collection of Canadian landscape painters and they were really interested in painting the sublime. They defined the sublime as this untouched wilderness, which of course, was a fallacy and a colonial fantasy as well because people were living on this land for many years before they arrived. But there is this idea, again, of the perverse impulse, the desire to be the first person coming upon a space feels really seductive. This feeling that you're the first person in this expansive land, discovering something, having a place all to yourself. So I wanted to approximate that feeling, that impulse and desire to be the first person, by creating paintings in which the viewer becomes the only figure in the space of the painting.

But I’m playing with this idea because the viewer feels like they're entering a space, but it's not a sublime untouched space. It's been touched by humans, they’re just not around.

Many of your recent paintings have a window motif, whether you're looking through the window or looking at the window. I wonder about this positioning of viewer as a sort of voyeur. Is that connected to your curiosity around perversity?

KS: I was thinking a lot about windows as the perfect way to illustrate our abstraction of nature. When there's a window between nature and us, we let in the light and feel part of the environment. But we don't have to deal with bugs or other parts of the outside world that might be less pleasant. So we're abstracting it into this aesthetic thing again.

But the window doubles this relationship because it is this aperture through which we can look back into the things that we've built when spending time outside. That brings up really interesting, very base emotions like envy, the desire to enter someone else's space. I was interested too in seeing from afar, across a threshold where you can't touch them. In these two paintings I wanted to illustrate two subject positions at once. You're looking out through the window and it flips and you're outside looking back into the window.

Given your interest in human perversity and the darker side of the human psyche, I'm curious about how you see these negative emotions impacting some sort of future.

KS: I think with any negative emotion, there's always the inverse that's working too. There's a lot of grief that's happening now and a lot of compassion and helplessness. I think those can be very positive emotions and impact our commitment to preserving or undoing some of the environmental damage that we have caused.

I think more cynically, the emotions or impulses that have led us to this point arise from an abstraction of nature. In the future, I think we're just going to apply those to humanity. I'm thinking about A.I. and the ways we are abstracting ourselves from the environment. Maybe there will be a time in our environment where context is irrelevant and we can be anywhere at any time and we don't have to worry about whether or not plants and animals are dying.

You construct these places that could be anywhere, they don't have the parameters of a certain city wilderness landscape. Does living in New York, which is this conspicuously constructed environment, have any impact on your work?

KS: I think so. I was very much more in nature and attuned to nature living in Canada where I grew up. Living in New York, you are often surrounded by facsimiles of nature like these really constructed boulevards with little patches of green.

I also feel that there is this thing living in New York, where this ambient idea of Upstate pervades our consciousness. It exists as this sort of heaven where some people venture and return and others stay. Then, there are some people who are just wishing for it and imagining it. This idea of Upstate is broad, it’s just this space that may be more livable or more natural. You're not there yet but you could be. And I think that's kind of what I'm getting at in making spaces that feel somewhat plausible to be in.

But there's still a sense of the spaces I paint being a little bit unrecognizable, a little bit strangely constructed or idealized, you're not quite sure how your body would actually fit in that space.

Yeah, a lot of your paintings are beautiful, but also kind of disturbing. There are no human figures and you don't know, as the viewer, where your point of entrance is, but something else that gives it that feeling is the color. You're working with these semi-natural spaces but injecting neon technicolors. How do you think about color and what role it plays in this natural vs. manmade dichotomy that you’re trying to upset?

KS: I think a lot about artificial nature. I love kitsch. I can trace my palette back to being a young kid and playing Super Mario. That is the first time that I encountered what I knew was an artificial representation of a kind of nature that I had never physically experienced. I’m thinking particularly of Donkey Kong and the jungle space. As a kid, seeing these kinds of plants in the game, I understood that they were real somewhere else, but I had never seen them except in photos. And then, suddenly I was experiencing this other abstraction of them.

So I'm using oversaturated colors or colors that are a little bit skewed from the natural, to evoke a simulation or a dream memory where everything feels recognizable, but a little bit off kilter. A little bit not right. I’m using color to destabilize things a little bit.

You also have a lot of green houses in your work. What's your interest in this space or idea?

KS: The Green House is one of the original spaces of constructed nature. You walk into a greenhouse and the plants are living as they should, and the climate is as it should be. But there's a feeling that if you took off the lid, everything would die. They're not able to survive without this protective structure. Whereas they would, of course, be surviving in their natural environment.

Something else interesting to me is that when something is really beautiful and desirable, you want to possess it. When you pick a flower from a plant, you know full well that it will die much sooner than if you just left it there. But you want to have it, you want it to be yours. So greenhouses relate a lot to that dangerous impulse.

In your work there are a lot of connections to the historical painting styles like landscape and still life. What sort of threads are you trying to pull from these historical painting methods? What do those methods mean in this day and age? What is landscape in 2021?

KS: Right now, I'm looking at a lot of 15th and 16th century painting, so Joachim Patinir, Bruegel, and then some Dürer engravings. When I look at these masters’ landscape paintings I feel a perceptible shift from religious painting to a secular landscape. Even though they still use religious imagery for the figures, I think the focus shifts significantly and they're addressing the landscape.

These paintings were made a long time ago, but also not if we think in geological time. The strangeness of perspective also gives them a deeply contemporary sense. I think there's also a quality that relates to a collapsing of physical space that we experience, for example, in Google Maps, where if you are on Street View and move really quickly everything blurs for a second and then fixes itself back into sharpness. I think about the ways that these sort of paintings do the same thing, where space acts as the representation of a lot of space condensed into viewpoints which I think relates to our experience of landscape now.

Often our idea of landscape comes less from the actual experience of a certain space and more from images that others have taken and given us. For example, I can conjure up the landscape of the Alps even though I've never been there. And that is so unlike the approach of these painters. Their imagination is coming into it, of course, but they're deeply engaged with and looking at the space around them as a reference point. So maybe it's also speaking to a desire to return to a kind of actual lived experience instead of one that is mediated through yet another screen or window.

We've talked about alienation and reintroducing strangeness into these scenes that have become kind of normal. What do you want a viewer to do with these emotions? Is there a political agenda, for lack of a better word, that you want people to take away and use in the present moment?

KS: I certainly don't think of myself as making didactic paintings. But I do think a lot about the threshold of how much you have to change something before it becomes just a little bit unrecognizable. So none of the objects or subjects or plants in my work are from imagination—they all exist, you can find them. So what is it that makes them feel unreal? Is it the perspective, the flattening?

I think if viewers came away with a sense of estrangement from the subjects that they're looking at that would be successful for me because in order to feel strange, I think you have to feel attached or familiar with something. And I think attachment or familiarity links to compassion and care.

Another question I’m trying to ask is how strange does our world need to become before alarm bells start going off? I think that's what socially and civically we've been dealing with for the last few years as well. At what point is the scale then tipped and its alarm bells? For me, the environmental alarm bells are going off and for a lot of other people too. It's important for me to talk through that threshold.