Uncovering the Heritage Silhouette: Lindsey Brittain Collins '21 BY

Uncovering the Heritage Silhouette is a bi-weekly series diving into how tradition influences the creation of art. We interview artists heavily influenced by their heritage.

Student Lindsey Brittain Collins is a painter working across multiple mediums including collage, sculpture, and installation to explore how architecture, economic structures, history, and aesthetics shape urban environments and racial perceptions. Her work confronts the erasure of blackness and spaces of blackness in history, such as African-American burial grounds and historically Black neighborhoods, raising questions of visibility and invisibility—shining a light on the stories of the people and places that have been overlooked. Her process is both heavily research-based while simultaneously spontaneous. Drawing on her academic background in business, economics, and sociology, she approaches the topics in her work through a critical lens.

Lindsey received her BA in Economics and Sociology from the University of Virginia and her MBA from Columbia Business School. In 2018 she was awarded a residency at the Vermont Studio Center and was appointed by Governor Northam to the Art & Architectural Review Board for the state of Virginia. In addition, she is the recipient of the 2019 Washington, DC Arena Stage Emerging Leader in the Arts Award. Lindsey lives and works in New York City and is currently an MFA Visual Arts candidate at Columbia University, anticipating graduation in 2021.

How do you define cultural heritage?

Lindsey Brittain Collins: I think this is a complex question for many people of African-American descent. I define my cultural heritage as Black. Black in the context of African-American history and culture and Black in the spirit of the creativity, ingenuity, perseverance, and love of the ancestors that came before me.

When I think about heritage, I think about the traditions, cultures, and values that have been passed down in my community and that have helped to shape my identity. The complexity of defining my cultural heritage lies in the meaning of the word “black.” Blackness is something that can’t be defined or contained—it’s complex and infinite, and constantly evolving.

What themes are you currently exploring in your work? Have they shifted over the years?

LBC: My work explores themes of race, economics, and the urban landscape. I’m interested in the sociocultural effects of architecture and how the urban landscape impacts the environment and the lives of the people in it—I’m interested in the emotions and histories of place. My work is rooted in social science and then I add layers of deep personal observation, emotion, and memory. Materiality is also essential to my work. The materials I work with allow me to explore themes of decay and the passing of time. I also like to think about how the materials can evoke qualities of urbanism.

While the themes in my work have remained consistent, the visual expression has shifted over the years. I work primarily in painting, but recently I’ve started to experiment with collage, sculpture, installation, poetry, and moving image. Even when I shift mediums, the work still has a painterly quality to it. My earlier work was deeply rooted in representation, but more recently, I’ve begun to play in the language of abstraction. I’ve found new freedom in allowing the work to live somewhere between these two languages of expression.

How has your physical environment informed and/or influenced your work as an artist?

LBC: My family is originally from the Washington, DC area, and I spent my early childhood there before moving to Princeton, NJ. Following undergrad, I moved to New York City and have been here ever since. New York City is the place I’ve lived the longest, and I consider both New York and DC to be home.

My work narrates my experience within urban landscapes, so the physical environment plays an essential role in all that I do. So far, I’ve focused on Washington, DC, New York City, and Charlottesville, VA (where I went to undergrad) as built environments of interest. Spending time in the spaces and watching them change is an integral part of my process. I’m interested in the temporality of the city, urban marks, and memories of place. I tend to focus on geographies where I’ve spent a lot of time, but I’m looking forward to expanding my practice outside of urban landscapes that I have a personal connection to.

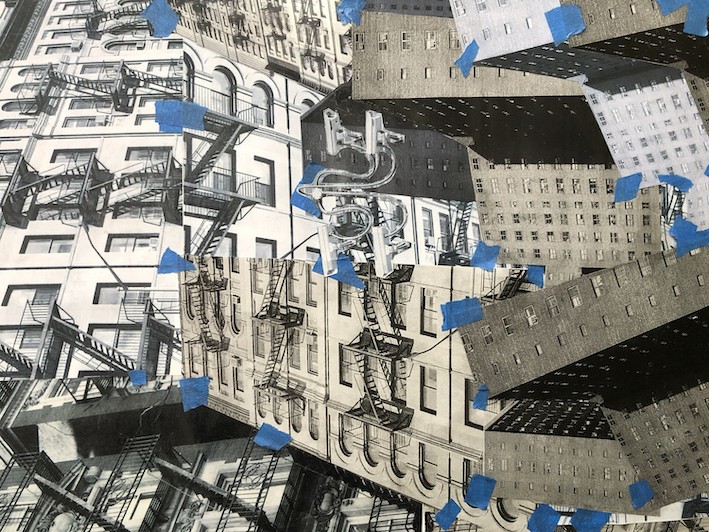

Can I hear about your piece, Anguish Reaching Into The Sky?

LBC: This piece was inspired by a social impact real estate investing class I took while I was in business school. The professor worked for a large investment bank and was in charge of their urban development group. For our final assignment, we were tasked with putting together a deal for land the bank planned to develop in Harlem. Even though there was a social component to the project, the social impact was overshadowed by profit maximization. After reflecting on the class experience, it struck me how easy it was to reduce the neighborhood residents—real people, with real names, real families, and real needs—to data points and variables in an Excel model. With that in mind, data’s dehumanizing and impersonal nature became the central theme in this work.

I decided to walk around Harlem and photograph the neighborhood on film as a way to reground myself and get a sense of how the area had changed since my time in business school. After I developed the film, I hung the images up on my studio wall and sat with them for a few days, hoping that inspiration for a painting would come to life. The more I sat with the images; the more compositions started to emerge. I made scans and then inkjet prints of the film and painstakingly hand cut and pieced together each image. I intuitively began to move the photos around like puzzle pieces, similar to manipulating the variables in Excel to formulate the perfect deal structure. Over time, I slowly built the large collage as you see it today.

I chose to assemble the composition with blue painter’s tape because it represents impermanence and hints to the viewer that the pieces within the collage, similar to the elements of a community, are movable. When you look at the painting from afar, you'll notice a graph made out of black tape that spans the entire width of the piece. In relation to the rest of the painting, this graph helps the blue tape take on the life of data points and representations of community members.

The piece is rooted in my reflections on my class experience, my memory of the Harlem I knew over a decade ago, and the feeling of encountering the architecture today. The more you spend time with work, the more the hidden narratives that I buried within the piece will slowly reveal themselves. The level of care that went into this piece’s composition is the level of care, compassion, and thoughtfulness that I wish profit-driven companies would take when redeveloping a neighborhood.

Your series No Name in the Street is inspired by James Baldwin’s work and also Georgetown. Can you tell me more about these pieces?

LBC: No Name in the Street is an older series of works that pay tribute to the lost Black history of the Georgetown neighborhood in Washington, DC. Georgetown was formerly the site of slave auctions and then later home to thousands of African-Americans. In fact, during the late 19th century, Georgetown was 34-45% black. No one talks about the neighborhood’s rich Black history as it is overshadowed by the wealth and retail that the neighborhood is known for today.

The title of the series, No Name on the Street, is inspired by James Baldwin’s fourth novel of the same title and Job 18:17: “His remembrance shall perish from the earth, and he shall have no name in the street.” This reference speaks to the erasure of community and culture and the ability of the authors of history to define the legacy of an entire people.

This body of work was my first time working with cement and found objects. I used concrete as a nod to displacement and redevelopment and as a way to evoke feelings of the built environment. The use of found objects allowed me to add a third dimension to each piece, juxtaposing the past and present. I used pigment from hammered brick shavings as a symbolic offering to the former Black residents of the neighborhood. Sadly, many Black residents were excluded from living in the brick homes of Georgetown, many of which still exist today, and were forced to live in wooden homes that were more susceptible to wind, rain, snow, and fire.

The paintings in the series highlight the Black church, the Black baseball league, successful Black businesses, the story of a Black burial ground and its mystery visitor, and the misrepresentation of my grandfather’s job title. The painting of my grandfather is the most personal piece I’ve made to date. The painting illustrates my grandfather at Georgetown Haberdashery, a white-owned business, and his place of employment. According to my mother, on record, his occupation was listed as the porter, but in reality, he was the master tailor. To me, this was the perfect example of the theme highlighted by the series title, No Name in the Street.

The process of making this work was a ritual of honor and respect. I hoped to celebrate and humanize the community of color that had been erased from Georgetown’s history.

You often look towards your own communities for inspiration for your work. Who are some of your greatest influences and how did they become your inspirations?

LBC: I love looking to history and my local community for inspiration in my work. Some of my greatest sources of inspiration have been members of the community. For example, one ongoing source of inspiration has been a little girl named Nannie, who died in 1856, just shy of her 8th birthday. When I was doing research for the No Name in the Street series, I learned about a Black graveyard in Georgetown that was thought to be a stop on the Underground Railroad. I decided to go visit the site, and while I was there, I discovered Nannie’s grave.

Nannie’s grave stuck out to me because someone left a collection of antique dolls at the base of her headstone. I wondered who it was that had a connection to a young girl who died so long ago. There was an energy that came from her grave that I can't articulate, but it drew me in. I went back to visit Nannie’s grave a year later, and someone left her another antique doll and a laminated birthday card. I’ve continued to visit Nannie’s grave over the years, and every year someone leaves her a new doll and a new birthday card. I know very little about Nannie’s life and ancestry, as her death predates death records, and her headstone does not have a last name. I also don't know who her mystery visitor is, but I continue to make paintings that document my encounters with her gravesite as a way to honor her memory and legacy.

I also look to many artists for inspiration. I draw inspiration from different artists, depending on what I’m working on, but some of the consistent artists have been Jack Whitten, Teresita Fernadez, Torkwase Dyson, Njideka Crosby, Julie Mehretu, and Theaster Gates.

How has the pandemic affected your art?

LBC: Being in graduate school during a pandemic, especially an MFA program that relies heavily on studio time, in-person studio visits, and collaboration, came with its own set of challenges. I can't say that the pandemic has directly affected my artwork, but it did impact my ability to make the work and how I choose to share it. COVID has caused me to rethink how I think about community, how I build community, and how I take care of my community.

What are you working on now? What can we look forward to?

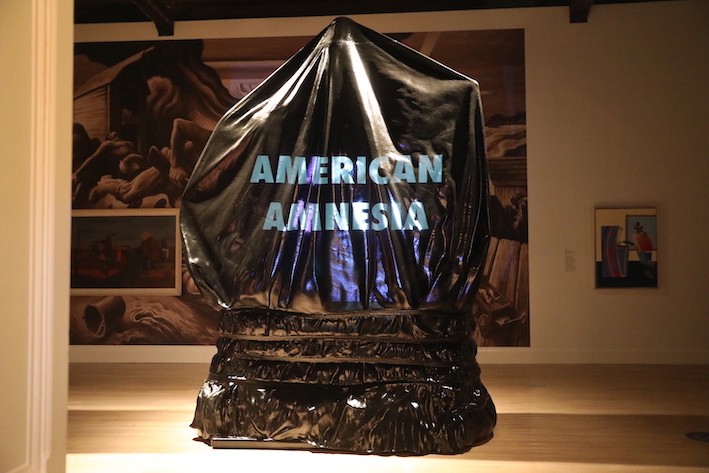

LBC: I just finished a video for the In Response program at the Jewish Museum that I’m excited about. I chose to respond to Jonathan Horowitz’s sculpture, Untitled (August 23, 2017 - February 18, 2018, Charlottesville, VA, which freezes the Robert E. Lee statue in Charlottesville, VA shrouded in a black tarp, as lawmakers debated what to do with the monument. I went to undergrad at The University of Virginia in Charlottesville, so this piece was a natural choice for my response. This is my first video piece, and the work narrates my experience confronting the Robert E. Lee statue while I was in Charlottesville, interrogating the purpose and placement of confederate monuments in America.