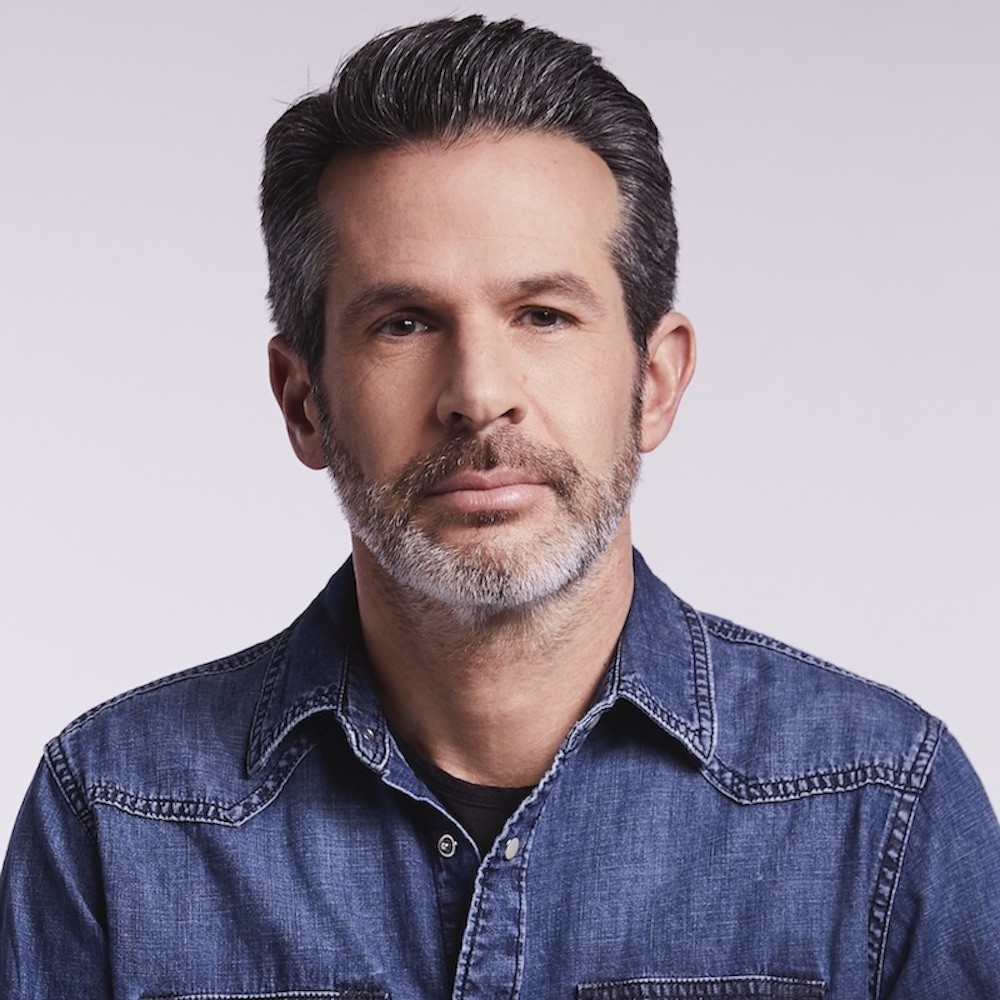

Out of the Past, Into the Future: Simon Kinberg '03

Out of the Past, Into the Future is a series that aims to chronicle a limitless scope of work by Columbia filmmakers representative of the past, present, and future. This series investigates how Columbia film projects, and the bespoke stories therein, are enmeshed with tales of history and experience, and harbingers of what’s to come.

This week we sat down with alumnus Simon Kinberg '03 to discuss how his films—including the X-Men and Deadpool franchises, Logan and The Martian—use past cinematic genres to convey ideas about the future.

Superhero films—from The Mark of Zorro (1920) to Captain Marvel (2019)— have intrigued a global fandom with the enigma of science fiction and characters who have strengths beyond human aptitude for decades. Based on the comics by Stan Lee and Jack Kirby, X-Men is one such superhero film series that dominates at the movie theaters.

Simon Kinberg, the winner of the Zaki Gordon Fellowship for Screenwriting at Columbia, is a coveted producer, writer, and director of the superhero X-Men franchise, including X-Men: The Last Stand, X-Men: Days of Future Past, X-Men: Apocalypse, Logan, and the Deadpool series. Most recently, he directed X-Men: Dark Phoenix, and the upcoming CIA-crime thriller, The 355. Additionally, he has produced such films as The Martian, Elysium, Fantastic Four, Murder on the Orient Express, This Means War, and is in development on a revival of Battlestar Galactica. He has also produced five television series: Legion, The Gifted, Designated Survivor, Star Wars Rebels, and The Twilight Zone.

That is to say, Simon Kinberg knows the superhero genre well. In his films, big names such as Patrick Stewart, Hugh Jackman, and Jennifer Lawrence portray shapeshifting mutants and telepaths. Stewart wields mind control unencumbered by electromagnetic force fields as the polyglot genius Professor Charles Xavier, and Jackman, as Wolverine, possesses healing factors that enable him to recover from bullet wounds and optic beam injury. Other characters harbor their prehensile appendages and superhuman dexterity. But Kinberg tells us, these futuristic films are guided by archaic genres such as the Western and film noir.

Implementing CGI and animation technology, the superhero genre demonstrates the ways in which vector fields, physics, Euclidean geometry and the inception of programming languages have culminated to make fantastic spectacle believable, from the use of cathode ray oscilloscopes to advanced computer graphics. Thus, superhero films use cutting edge technology, and allude to the canon of cinematic genres, to galvanize powerful possibilities about the future of humankind, but when it comes to the storylines, the influences are less futuristic and more, time-honored genre.

As befits a creative producer, Simon Kinberg began his career writing screenplays. While his first major Hollywood screenwriting project was Mr. and Mrs. Smith, which he penned as his thesis at Columbia, his very first screenplay was called Ghouls of New York.

“Ghouls was the first feature that I ever wrote,” Kinberg said. “I'd never written a feature screenplay before that, and I started it in, I believe my first year there [Columbia]. My professor was Malia Scotch Marmo, a great screenwriter and a really, really wonderful teacher for me. Some people in the program had written features before, but I had not. Screenwriting was very new to me.”

Ghouls of New York is based on the story remembered as the “crime of the nineteenth century,” set against New York’s most crime-ridden and raucous era, when gangs ruled the streets, pirates ran the rivers, and riots filled the squares. It is about two criminal masterminds from opposite worlds who come together to execute the biggest heist of the century: kidnapping the dead body of New York’s richest man.

Kinberg initially pitched Ghouls of New York in a class with Professor Ira Deutchman. “He liked the idea, and asked if he could read it,” Kinberg said. “It was never bought by a studio, but I got tons of meetings with studios, production companies, agents, lawyers, and managers. So that script, that was obviously never made and never sold, did start my career.”

As a youth, Kinberg exalted the “Mount Rushmore” heads of genre storytelling, including Stephen Spielberg, George Lucas, and James Cameron, but he said that he hoped to make prose writing his métier. He studied English Language and Literature at Brown University, where he was inducted into Phi Beta Kappa. His favorite authors were those of 1920’s and 30’s high modern literature, among them Hemingway, Fitzgerald, Joyce, Eliot, Hughes, and Faulkner.

Yet, when he wrote, his prose was increasingly cinematic. “If enough people tell you you’re drunk, sit down, and if enough people tell you you’re a screenwriter, go to screenwriting school,” Kinberg said of the impetus to becoming a screenwriter. He viewed the world cinematically.

Kinberg was heavily influenced by what he called “The Golden Age” of genre storytelling, most especially Star Wars, and films like Die Hard, Beverly Hills Cop, Lethal Weapon, and ET. “There were all of these really great movies that were slightly different than the genre often is today, though I think it’s kind of starting to lean back in that direction, and they were very character driven,” Kinberg said of those films that were most influential to him. “Creatively, having said that, I obviously also loved the movies of Stanley Kubrick and Antonioni.”

Ghouls of New York connected Kinberg to the industry, and he later found success with his thesis project Mr. and Mrs. Smith, which was eventually greenlit by producer Akiva Goldsman, and starred Angelina Jolie and Brad Pitt. He worked with director Doug Liman on the film, who later asked him to produce the film Jumper, which would become Kinberg’s first producing credit.

Following the success of Mr. and Mrs. Smith, Kinberg became involved with the X-Men films, which were produced by The Donner’s Company and Marvel Entertainment. In 2005, Kinberg had a general meeting with Avi Arad, who was the founder of Marvel Studios, now run by Kevin Feige. At the midnight premiere screening of Spider-Man 2, at the Arclight Cinema in Los Angeles, Kinberg met with Arad and Feige, where he had auspiciously been assigned to row X.

“I was like, look guys, I don't know if this is an omen, but row X! Avi said, hold on to that. Bryan Singer was just in the process of leaving the X-Men franchise after X-Men 2, so they needed a whole new team. I think like a week later I got a call from Avi saying—he knew how much I was an X-Men fan, of the comics and of the movies—I think it was a real omen, are you interested in writing X-Men 3? And I said, yeah, totally. I wrote it, and then Zak Penn came on and we co-wrote it together.”

After writing X-Men: The Last Stand, Kinberg went on to write Jumper, Sherlock Holmes and This Means War, before writing X-Men: Days of Future Past and X-Men: Apocalypse for 20th Century Fox and Marvel, and producing the Deadpool series, Logan, The Martian, and Elysium. In 2019, he directed his first feature film, X-Men: Dark Phoenix, and last year, he wrote his first original spec script, Here Comes the Flood, which will be directed by Jason Bateman.

Kinberg, who has spent time with Star Wars creator George Lucas, said that he is able to identify several genres in Star Wars movies, “Star Wars is a hodgepodge of so many different genres. It's Samurai movies, it's Westerns, it's World War II movies. Having spent time with George Lucas working on not just Star Wars Rebels, but also some of the recent Star Wars films, which I came in to either rewrite or just work on, George was very inspired by every possible genre.”

For good measure, Star Wars is an allusion to, or an allegory for, the Western. The film Logan, which follows Wolverine in a nebulous cross-country future, where the mutants of the X-Men universe are nearly extinct, is lucidly inspired by the 1953 Western, Shane. The Western frontier setting of red-rock cliffs, along with themes of belonging and familial justice, are what catalogue Logan as a Western.

There are both indirect and explicit references to Shane in Logan. When Logan, Charles Xavier, and Laura are hiding in a casino, they watch Shane on the hotel television. Both films also incorporate the theme of a hero who perishes, the harrowing guilt of killing for the greater good, cinematography of the child’s gaze, and the necessity of riding off into the sunset, rather than celebrating a victory—all elements of Westerns that appear in Logan. In fact, the director, alumnus James Mangold '99, wrote an essay about the naturalism and humility of Shane for a special screening of the film, at the Academy of Motion Picture Arts and Sciences, which can be read here.

“In the case of Logan, it’s a Western, in the case of Days of Future Past, it's a time travel movie, in the case of Apocalypse, it's a task movie,” Kinberg said. “We find a structural paradigm and graft our characters and some of our themes onto that spine. I think what it gave these kinds of movies is a new sense of the hero. The hero in American cinema is defined in the Western. And I think that's what's happening now: The notion of what it is to be heroic is getting refined, and in some ways, deconstructed. But it's still based on that sort of primary source. The tension in the movie comes from the fact that Logan is a deadbeat dad who is refusing the responsibility of being a parent.”

While Logan makes reference to the Western, Deadpool is more reminiscent of Hollywood, and tawdry gossip in the industry itself. Spearheaded by Ryan Reynolds and Rob Liefeld, Kinberg called Deadpool the most uniquely marketed film he has worked on. “There are a lot of genius, insane brains behind Deadpool,” Kinberg said. “We made that movie cheaply in comparison to other superhero films. We thought we'd find a niche audience or the audience that reads the Deadpool comics and it broadened out to demographics. It was also much more of a female audience than we thought for an R-rated, incredibly violent action film. It just exploded in a way that we didn't anticipate.”

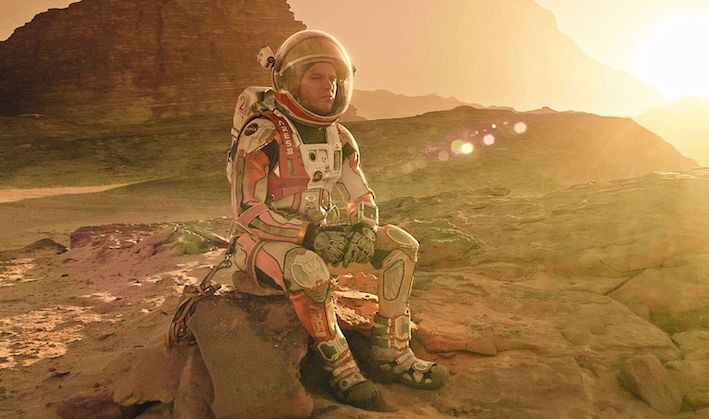

While the history of the cinematic genre inspires all of Kinberg’s work, he also looks to the future when deciding what projects to write, direct, or produce. “I do an immense amount of research, for every movie that I work on to understand the characters better,” Kinberg said. “And sometimes to understand science or technology better. For The Martian, a lot of it was, I mean, all of it was there from Andy Weir's book and from Drew Goddard’s script, but I wanted to understand it. And so I spent time at JPL (Jet Propulsion Laboratory) and talking to some NASA folks so that I could at least have some sort of grammar to be able to enter into the conversations with Drew and Andy and ultimately Ridley Scott who directed it, and Matt Damon. Elysium was another science fiction movie where I talked a lot with Neill Blomkamp.”

When asked if he expects to see mutants in the future, Kinberg said, “I mean, probably there will be, just because human evolution will lead us to a new place. We used to have tails, now we don't have tails. But, you know, the way I look at the mutants in X-Men is very much the way that I know Stan Lee intended them, which is that they are a metaphor for any persecuted or oppressed group. They’re a metaphor for people of color, the LGBTQIA community, Jews, women, I mean anyone that has felt ostracized. Anyone that's experienced a form of xenophobia. That's what X-Men is about. And I think that's why it's so powerful. And I think that's why it has endured.”

Kinberg said that whenever we write, we inevitably bring something of ourselves into the writing. However, he never writes, or doesn’t intend to write, autobiographically in his screenplays. “To be explicit, I can’t write something that is an expression of something I’ve gone through, or something I’m going through. I would say I identify with dilemmas that the characters go through, or I identify with, in some ways, the thematics of the movie and the thematics of the movie are expressed obviously through the characters. So there's not one character that I could say, ‘Oh yeah, Logan is really based on me, or Sherlock Holmes is based on me.’”

Yet Kinberg said that writing the character of Mr. Smith [Brad Pitt] came from an emotional appeal: “I was in a relationship with a woman at the time, who said to me that I was really good in the relationship and present when we were in conflict, but then when things were stable, I was kind of absent. And I was thinking about that. I was very young, I was in my twenties, and I was like, you know, that's true for me, and interesting dramatically, so how could I turn that into a story? And so that evolved into a story about two people who were absent in their stable marriage, and they get reignited through conflict, for Mr. and Mrs. Smith, Brad and Angie, which then gets them falling in love again.”

A film is untethered if it does not have a visceral connection to the writer, Kinberg opined. There are select characters whom he identifies more sentimentally with, in terms of the pangs they encounter and their nonpareil structure. Two of these more nuanced characters are Charles Xavier in X-Men: Days of Future Past, and Sherlock in Sherlock Holmes. “The person who has the biggest arc is the person whom I define as the protagonist, and Charles has the biggest arc by far in the movie,” Kinberg said. “The throughline of the movie for me is Xavier finding his hope, which I identify with, even if Wolverine is the most present in the movie. Sherlock Holmes is a romance and a mystery, but for me it’s really about a guy who has to let go of a friendship. Watson’s getting married, and Sherlock has to learn to let go of his best friend. He has to learn to share with Watson’s bride. And I was going through something similar where I had a best friend, who was a huge part of my life, who was getting married.”

To aspiring filmmakers, Kinberg said, “Chase only things that you want. Because that way, whatever it is that you're working on will be authentic, and will be yours. And you will actually enjoy the process better, because the process is hard. It's hard writing, it's hard making a movie, and you want to be doing it for the right reason. And the right reason is because it’s a story that you have to tell with a level of commitment, passion, and clarity, and if you don't have to tell it, it's not going to get told.”

Read more from the 'Out of the Past, Into the Future" series here.