Diversity in Film: Moara Passoni

Diversity in Film is a bi-weekly series covering underrepresented groups in Film.

This week, we sat down with current student Moara Passoni.

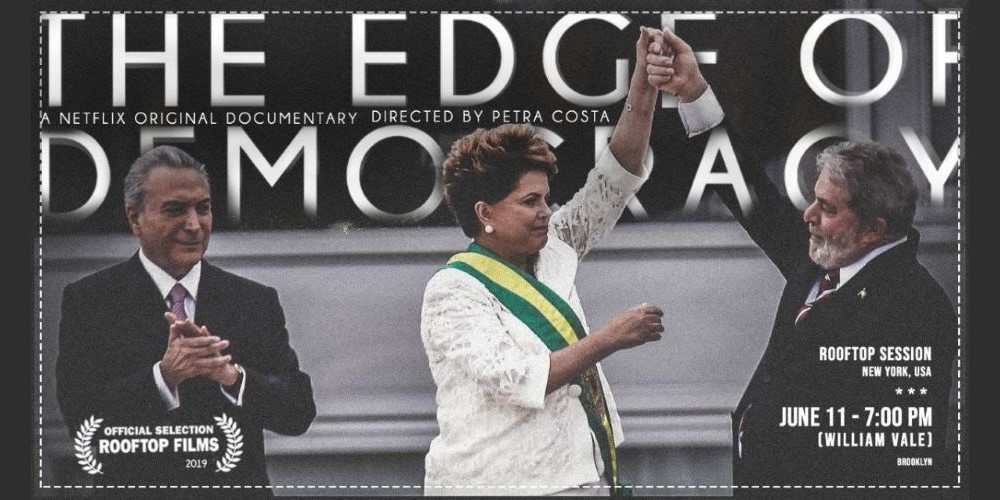

As co-writer and associate producer of the Oscar-nominated documentary The Edge of Democracy, Passoni cites influences from legends like Glauber Rocha and Lucrecia Martel to her own friend, director Petra Costa. In this interview, we discuss COVID-19’s impact on Brazil, helping Costa find her voice in The Edge of Democracy, and the blurred lines between fiction and documentary.

You’re in São Paulo now, right? What’s the atmosphere like when you go outside? Here in New York City, it’s very eerie.

Moara Passoni: I’m totally locked down, so I haven’t been on the streets for ten days now. What I see from my apartment is that the streets are quite empty. There is a lot of apprehension.

Are you the kind of person who loves staying inside, or are you going a little crazy?

MP: I’m going a little crazy. I love walking around. What inspires me is having contact with people and walking around and feeling the world, even if I need to come back and write in solitude afterward. Of course, I talk to people all day long [on the phone], but at the same time, this feeling of being inside without being able to leave drives a lot of anxiety. I’m trying to learn how to connect with people in a new way.

I’m also releasing my debut documentary as a director, Êxtase, which talks about anorexia, and it’s crazy because the condition of the character is quite similar to what’s happening in the world right now [staying inside, isolated from other people]. I feel we are in this moment where we are understanding that we are all connected to each other, and that the solution is not going to come individually if we do not act together. For the first time, something that happened on the other side of the world is directly affecting us, so we have a very concrete feeling that we are a global community. I think it’s the first time in history we’ve had this perspective so concretely, and I feel that those relationships and the way we think about ourselves will not be the same anymore. I hope we take this as a moment to change for good. To rethink our model of society.

We’ll come back to your documentary, but I’m also wondering how it feels to come home during such a strange time.

MP: It is very weird to come back to Brazil right now, in this moment of lockdown. But I felt that if I wasn’t here at this moment, maybe I would never understand what happened to this society. I needed to be here to understand what a huge, social shift it’s going to be.

How has your relationship to coming home changed since Petra Costa released The Edge of Democracy, which you co-wrote and associate produced. The film had huge viewership in Brazil, right?

MP: Yes.

I think even when we were making The Edge of Democracy, there was always this question about how what’s happening in Brazil connected to other places, because the rise of authoritarianism and fascism is not happening only in Brazil. It’s all around. So we were all the time looking at Brazil but also trying to have a broader perspective. I think the fact that I left Brazil four or five years ago also allows me to come back and see it more clearly because I don’t have this one hundred percent identification.

Do you feel a gap between yourself and Brazil?

MP: I don’t feel a gap. But when I’m in Brazil, I don’t feel like I’m super from here anymore. I’ve been living here, in Cuba, in France, and in the U.S., and I keep telling stories about Brazil because they speak strongly to me, and the way I understand myself is related to that. But nowadays I see myself in this condition where I don’t know exactly what my identity is. But what I’ve noticed is that some things are better when you have this distance. Because when you are completely mixed up in things, it’s hard to see. You’re just immersed in your world.

We’re now becoming more about this global community than only about Brazil. We have so much social injustice [in Brazil], from social class and racial prejudice to the problems with the Amazon and the genocide of the native population. If there’s one thing that I try to understand all the time, it’s this heritage from slavery, and how our social relationships deal with that and are permeated by that all the time I see now that when our president [talks about protecting the economy over lives during the pandemic], it’s reproducing this thought somehow. Many questions. I think I’m in a place where I have more questions than answers.

I think that’s how everyone feels right now. It’s not necessarily a bad thing, as long as we let the answers change things when they come. That’s what I’m most scared of: If this doesn’t change things, nothing will.

MP: I think we are understanding for the first time that an individual is not an individual. We are connected to other people, and that's how things work. And then I think the question of love and community comes back in a very strong way.

I’m also curious about gender and The Edge of Democracy. It’s a very female-driven film, which people don’t often talk about because it’s not about that.

MP: Yeah, most of the team is female, which was an important factor in shaping the film. In Brazil, our first female president was unfairly impeached. Telling this story with a majority female crew brought an essential perspective to the film.

Something that I’m deeply interested in is understanding how as individuals with our own life stories, private concerns, and dreams, we are connected to politics. This is quite fascinating and transforms politics into something more accessible and less taboo somehow: How does politics affect our feelings, our psyche, our bodies? This is maybe a very female perspective on politics, and a fundamental one.

There is a historian called [Jules] Michelet, and the French writer Marguerite Duras quoted him once; he says that in the old times, the men went away because of wars, and the women stayed home. And what happened is that these women started talking with the plants and with the animals, and they started developing their own language. And this language is the language of freedom. I think what The Edge of Democracy has that’s quite fascinating is this freedom, or even audacity and courage, that Petra had to talk about her personal life as interwoven with politics.

And what I see with The Edge of Democracy is a very specific voice—Petra’s voice—telling her story from a very specific place. Of course, her life story was intertwined with Brazil’s history. Her personal view captured momentous aspects of our country’s recent political history. This is also what brings authenticity to the film. The personal is political, as the feminist maxim goes.

But it was not easy for Petra, or anyone from her team, to find her voice in the film, or her own “language of freedom,” so to speak. Myself included, as a writer and producer; it was not easy to help Petra find her voice in the film, especially as it required us to undertake tremendous research. We had a lot of discussions amongst ourselves. We had to go against official narratives and constantly ask “what is going on here?” as the reality was unfolding in ways that sometimes seemed almost surreal. And we also had to negotiate with the men on the team. That was a political experience too.

What’s interesting too is that her perspective is a female one, yes, but it’s also one of privilege. What did those conversations look like?

MP: In making documentaries, you must be honest and transparent with regards to your point of view. And we knew from the beginning that if we were not upfront about Petra’s political leanings and family history, the film would not be viable. We would have been manipulating the story in a biased and unethical way. First, it was necessary that we fact-checked and proved everything in the film. And secondly, we were transparent about the perspective of the film. We are not human beings just floating around unbounded from context and political leanings. We always speak from a certain perspective, and acknowledging that perspective is important.

I want to explain a bit more. Brazil is a country where, until 2002, cinema was mostly reserved for those who had the financial resources to make films. While we did have some very important filmmakers who were not from this economic elite, for the most part, only those who had access to money could make films. However, our country spent about twelve years building public policies for cinema and media literacy, so a lot of people were able to study cinema and learn how to access public funding so they could propose their own films. Still, this was not the whole population. There were several communities, like black women, that had to fight to get their stories told. And at some point they understood they needed to create their own channels for the production and distribution of their films. In distribution, there was an even bigger gap. Anyway, progress was being made and new voices arose in our cinema. But now, with this new regime, they say they need to “curate” what kind of films will be produced. We all know what “curate” means, right? And in a moment like that, who can make films? Who has access to the resources?

Right. And I don’t ask that question to ‘ask the tough questions,’ so to speak, but you can’t talk about Petra’s access in that film without talking about privilege. However, it is true what you said, because you don’t feel a third-person narrator, you feel Petra.

MP: Exactly. There is such clarity in her voice and vision. There is one film by another Brazilian, João Salles, called Santiago. Santiago was a butler for his very wealthy family in Rio and a fascinating guy.

By the end of the film, Salles says something like, “but when Santiago finally tried to tell me something most intimate, I didn’t turn the camera on.” Salles problematizes how the director has “authority” over the discourse in a film. And he admits that he might never know the most important thing Santiago had to tell him. He also talks about the limits of his perspective. There is a class difference between him and Santiago that is an invisible wall. You cannot understand Brazil without understanding social class, racial dynamics, and how that informs the relationships between people. And I think you can’t understand cinema without understanding what is implied in your way of seeing, feeling, framing, and narrating the world.

I’ve never been to Brazil, but even when you see pictures of Rio de Janeiro, the class segregation is so visually present.

MP: In Rio, it is much more evident. São Paulo is very segregated, so the poorer neighborhoods are normally far away from the very rich neighborhoods. Not always, but frequently. In Rio, it’s very striking, because you have this contrast showing up. And we learned how to transform that into something normal, which is horrible. It’s absolutely scary. And with this crisis now, it’s even more scary.

I want to come back to your documentary, Êxtase, your most recent accomplishment of many. I remember you saying a while ago that you didn’t want to make documentaries anymore, only fiction films, which is funny, because suddenly all these documentaries you’ve made are coming out.

MP: I know! I think documentaries control your life much more than you control them. And there’s a limit in docs about how close you can get to someone and all the important ethical boundaries we set. It’s different in fiction. You can reach people more intimately. So I think I want to work with fiction because of that.

This year was interesting, because I had a film that was nominated for an Oscar and an avant-garde film, and I really like navigating between these two. I think The Edge of Democracy is a film where the facts are very important, even if the personal perspective is there. We were telling a story that really happened, and we had all the facts, and we had to prove every single thing we said. It’s very different from what I did in Êxtase, where the frontier between dreams and what’s real is way less important. I’m much more interested in the character’s inner world and how she experiences everything around her. In other words, the reality of her psyche.

This is what the film is about: how she understands and experiences the world around her. I tried to put the audience close to the psyche of this character, and it’s a character that’s living the process of anorexia. In this process, there’s a lot of delirium that mixes with reality, and I was interested in this delirium.

I love Buñuel, and he did a short film called Las Hurdes: Tierra Sin Pan, or Earth without Bread, where he documented a community that lived in total poverty in Spain. But he invented this community, this story, and he was accused of being unethical. And he said something like, “Okay, maybe this community does not exist, but take ten steps and you’ll find another community that’s exactly like it.” Sometimes fiction and the reality of dreams allows you to go way further and way deeper.

What do you mean when you call this an experimental documentary?

MP: It is neither fiction nor a documentary. The film is a mix of archival material and other images I produced with actresses that are playing a role and images that express how these characters see and experience the world. The whole screenplay was written from intimate journals of women suffering from anorexia, and all the scenes refer to something that happened in reality, but they are not reconstructions. I’m not trying to document something that happened, but to penetrate into the minds of these characters. It’s much more about trying to bring the audience close to this character, close to the suffering, so we can humanize it and understand that in their suffering, there’s something that’s not only about that individual, there’s something that relates to me and to you and to other people when we are talking about anorexia.

The anorexic body is super sensationalized, and you get very seduced by that. When you see it, it’s hard to do anything else but pay attention to those destroyed bodies and the limits of life and death. I wanted to penetrate how this woman is seeing her world. Of course the reality of her body is super important, but it’s also super important to understand how strong what she’s living in her head is. I had anorexia, and for example, I gained a lot of pleasure in the process. And as long as I could not understand that pleasure, I would never get out of the anorexia.

The way I found to humanize this experience was by bringing actresses who could play this woman trying to find a way of growing up, a woman who does not see in the women or adults that we have available, a model that she can fit into. She has to somehow invent her own way. Even if there is a disease going on there, there is also an idea of trying to find a place for herself and trying to understand herself in this world.

The film is playing at a festival currently, right?

MP: There is this festival called CPH:DOX, which is considered one of the most important documentary film festivals in the world. They really love bold documentaries that exist in this frontier between fiction and documentary. We are in the main competition. But one week before we would’ve released the film there, the festival cancelled the physical version and decided to make this virtual version, which was great because at least we did not let things die.

It’s weird, I started working on this project even before I met Petra. It’s a very difficult experience to articulate in a film, and I struggled a lot to find a language in the film that could express all this craziness and contradiction inside a woman suffering from anorexia. The character is, for the most part, isolated from others, and there is this refusal of the outside world. And it’s quite strange, because I thought if we could release the film in a theater, I would finally implode this anorexic body that's so isolated. I thought, “Finally, I’m transforming this experience into something that goes beyond the individual.” And then it went virtual, and people are watching the film in a very similar condition to the character [isolated and alone]. I did this film always thinking about a theater: the big screen, and the dark room, and you learn the most about filmmaking when you show the film, feeling people’s reaction to your work. This is super important. It’s weird, I only know [how people are reacting to the film] from the people who write about it, and thank God, the reviews are positive.

Could the viewing experience be enhanced by the fact that we’re all sitting inside, just like the character?

MP: Yes, but at the same time, it’s a very immersive film, so the sound is super important, and the size of the screen. Of course, the film can be seen on a laptop, and what you said makes a lot of sense for this film, but in the theater, you really dive into the experience.

What are you working on now? What’s getting you through your own COVID-19 isolation?

MP: I’m working on an article and treatment about the history of “Democracia Corintiana.” Brazil had been a dictatorship since 1964, and the soccer clubs in Brazil are the most authoritarian places you can find. It almost mirrors the government in this sense. And in the middle of one such soccer club, they developed a democracy. They would decide collectively on every decision that would affect the group, and they started engaging politically. There were some fascinating footballers. Sócrates, who was a doctor, an intellectual, and genius at soccer. Casagrande, who was a counterculture 18 year-old top scorer. Wladmir, who combined soccer, jazz, and capoeira. Together they had to “invent” a democracy, as they had grown up in a country under dictatorship and had no idea about how a democracy works. It’s a beautiful exercise in freedom, and there is something in it that fascinates me, because even the way they played soccer transformed a lot. Some of them brought art to the way they were playing. So I’m writing about that story, and then I’m trying to go back to editing my short films from Columbia.

You have two feature scripts you’re working on too, right?

MP: Yes. One is about these housewives in the 1970s who became political leaders. And the other is about this little girl who feels the pain of the world, and it’s a kind of horror-social film.

I want to see that!

MP: Me too!