Conversations with Artists in Art Getting Art: Rasel Ahmed '21

Conversations with Artists in Art Getting Art is a bi-weekly series and a play on Jerry Seinfeld's Comedians in Cars Getting Coffee. We interview artists about their art and 'getting art'.

Here, we talk with Rasel Ahmed '21, a recipient of the prestigious Davis Putter Scholarship, about pronoun paradigms, exile, and drag performers.

Rasel Ahmed ’21 is a former textile engineer turned experimental filmmaker in his second year of the Visual Arts MFA program. His approach of infinite mutability toward art forms is a protective measure as much as it is a creative source. Though Ahmed now considers his textile engineering days a thing of the past, no gesture, encounter, or experience is wasted in his creative output. Rather than writing out strict character guidelines for his actors, Ahmed holds lengthy conceptual sessions to merge actor with character. Together, they discuss the character’s past, the actor’s past; he prefers interpretation to dictation. Ahmed’s most recent project—for which there were many such conceptual sessions—was a murder mystery, filmed at the very beginning of the pandemic.

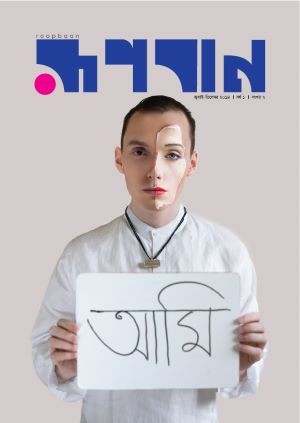

Ahmed says that his time working as one of the founding editors of Bangladesh’s first LGBTQ magazine Roopbaan has informed his visual practice. The spirit of collaboration and community-facing work emerges as a common theme in Ahmed’s otherwise visually, constantly evolving pieces.

Before we begin, I use pronouns she/her. What pronouns do you use?

RA: I use the he/him pronouns, but I don’t identify myself as someone of the male gender. And I think this is a complicated relationship that I’m exploring more and more. I was in this meeting with a therapist yesterday, and they asked the same question: what pronouns do I use, or what gender do I use, and I said the same thing. And then the therapist said, “That means you’re gender non-conforming.” I don’t think so—I do want to identify myself as a man, but to dismantle the idea of man, of gender. I was watching this lecture series by Shohini Ghosh and she was talking about misreading queerness in film. From there, I started thinking about this idea, this really radical idea, that misgendering could be an act of dismantling gender. In this way, I identify myself as a man, but it’s a misgendering—it’s not who I am. Misgendering as an act of dismantling gender is my proposition.

The intention of misgendering oneself is dismantling? Is dismantling a deliberate self-misgendering or vice versa?

RA: Yeah, I think if you really want to dismantle the entire hierarchy of gender, then everybody should be “they/them.” No one should be “he/she.” Adding a noncomforming category ]replicates the structure of gender into it. This is the conversation I’m having with myself, and I think I will be more and more vocal about this because our relationship with gender is complex. I mean, how is my experience of being a man similar to any other man’s experience?

I was just reading what you wrote about Roopbaan, the magazine you published and co-founded in 2014. Could you tell me more about it?

RA: This was an act of friendship that turned into political activism. People that I co-founded the magazine with were friends in the community, and then it turned into something we wanted to explore, which is queerness in our friendship, queerness in our society, queerness in political justice. I was frustrated with my engineering, because I was almost forced to study it. Roopbaan saved me. Right after it went live, it garnered a lot of attention, mostly negative. We printed two issues, it was really difficult to publish the second issue after the backlash we received as a Bangladeshi gay magazine.. My involvement with the magazine was as its sole editor. In 2016 Roopbaan was targeted by Al Qaeda, and the co-founder Xulhaz Mannan was murdered. I don’t know if I want to talk about it. I mean I do talk about it, but it’s a lot of unprocessed trauma, especially my close friendship with Xulhaz.

I can tell you this: I’m really reliving—I mean, this conversation is not traumatizing—but there was recently a gruesome murder in Lower Manhattan. That guy actually had set up a huge, multi-million dollar ride-hailing service in Bangladesh, so this news is widely covered in Bangladesh. Reading that news was difficult for me. To have some of the flashbacks of 2016 when my friends were attacked, and I survived, but my friends didn’t—I was not in the place where they were attacked, but we were all living in that fear. Reading the news of Fahim Saleh, the guy who was recently killed, actually brought me back to my friends who were hacked with a machete. I was lately thinking about cutting as a theme for my work.. Reading that was tough for me. Sorry for all this traumatic retellings.

No, I’m sorry. If you don’t feel comfortable sharing, let me know. But this magazine sounds like a major point in your life.

RA: It is. Even the work I’m doing right now, and the way I think, everything has been impacted by the work I did in this magazine. My relationships and collaborations and ways of thinking have all been impacted by this.

At the time, how did you circulate the magazine?

RA: It was all physical. In the beginning we were selling it, because we were all volunteering our time, but when it became dangerous we started developing relationships with fashion boutiques, cultural institutes, bookstores, all in Bangladesh. In 2015 I worked on a flashcard comic project of developing a Bangladeshi lesbian comic heroine, and by then I was very used to getting threatening messages and learned how to navigate this as a part of our work.

I read here, also, in your text, that you had to make a hasty decision to leave Bangladesh. I can’t imagine what it must have been like to leave home under such trying circumstances. What was that like?

RA: It was uncertain. I left without knowing that I was leaving forever. It was a temporary relocation that became permanent. I explore the idea of displacement in my work a lot. When I think of displacement, I think of both internal and external displacement, you know. What is all this memory I carry in my body, always moving and shifting and changing. The thing I’m telling you right now might not be my direct experience. Displacement is the natural state of being, but in the world we live in, displacement generates a lot of trauma. In my work I’m also politically and philosophically trying to explore what it means to be displaced, what it means to leave something you don’t want to leave, which when left behind, becomes part of you. Your displacement is you.

Recently, I’m considering collaborating with two other artists, both in Australia. We’re thinking about creating a theatre production about displacement but working remotely. And in this post-covid world, what is displacement? Lockdown, micro exile. You cannot do certain things. When I first came to America I had this notion that I was in exile for my political activism, but now four years later, COVID-19 happened and that created another exile. Before that, I couldn’t leave the country—I was living by an already exhausting list of things I could and could not do, and then COVID-19 happened. Surprisingly, this was kind of liberating for me, to see other people in an emergency too. One thing I say is that we’re always in an emergency, at least one of us, you know? We don’t often realize that, because we have our privilege, our way of living.

In the theatre project, we are imagining displacement as social power, as something that gives you agency. I think this is the way I can survive this constant anxiety.

Even though I can go out and I am not in fear of my life like I was in Bangladesh for a long time, someone like Fahim Saleh gets murdered, and I’m back to square one. This is what I’m experiencing everyday, and the only way I can express it is to make fun of it or make art of it, think of it politically. With the theatre performance, we are trying to approach displacement as a pedagogical event. Displacement is where we learn how to celebrate change in our lives.

I am a person who is in the margin who constantly needs to transcend—to change the meaning of it, like how I change the meaning of my gender. I have to constantly push and change because it’s always attacking me. Citizenship, border, home, kinship, relationship. Sexual orientation. Displacement, loneliness. I have to push it back and really subvert the meaning.

Interesting that you choose the form of theatre performance.

RA: I’ve done some site-specific experimental theatre in which the audience would become part of the theatre and the performers would be part of the audience, and performers interacting with hybrid mediums. The theatre was documentary style, but there was a performance going on too, singing. I use a lot of archival materials in my work. I don’t necessarily see a separation in these mediums. When I think about theatre, I don’t think about how people will read it, but rather how I can contain or place this idea into that place. Using theatre as a placeholder for my ideas.

What does your work look like?

RA: I’ve recently finished working on an experimental film called Who Killed Taniya? It’s an experimental murder mystery film...But I don’t necessarily know which part of my work is the final version. For instance, maybe I make a film but the script is more what I feel is my work, the finished work, while the film is in progress.

Paint me a picture with words. Over Zoom, it’s not as easy to get a look around at people’s works while we chat…we lose the shared physical space.

RA: I do like film and moving images, so it’s not necessarily one picture—it’s always moving and shifting. Lately, in my visual practice, I’m exploring experimentation and abstraction, which has not necessarily been the way I work before. I’m enjoying the world of cinema, abstraction, which is the way a lot of visual artists communicate with each other. I’m a conceptual filmmaker, so although you see my film which is a visual thing that is driving me through all the processes I do, it’s the conceptual intellectual argument that is the spirit and philosophy of my work.

You gave me an example of this earlier, with displacement as a starting concept that would be fleshed out in a theatre production. What other forms have your conceptual work taken?

RA: Immigration, queer kinship,citizenship, memory. The last film I just mentioned, Who Killed Taniya?, is the story of five drag performers. They are in this green room space getting ready for a performance, but while they’re doing it (and in my film there is no dialogue so they communicate with each other through body language and the sounds they make) they manifest silent dialects. One of the performers gets murdered. But through this I am kind of experimenting with different ideas such as drag as a conceptual lens to look at the performative aspect of citizenship and borders. Borders are extremely performative. There’s this wall, this massive piece of performance.

This movie also takes place in the future, where there are a lot of immigrants, refugees, and they’re all queer, and they’re bringing all their experiences of trauma, and they are projecting this onto each other, they are violent towards each other, and in the end they kill each other.

Did you hire actors?

RA: No, I collaborated with drag performers. I don’t do drag myself, but I’ve organized and heavily participated in drag performances, and I wanted to engage with a community that I’m already engaging with, the South Asian queer diaspora community in the US. So I reached out to my friends and told them what I wanted to do, and asked them how they saw this.

This film is coming out of an archival project as well. I have a massive collection of the underground organizing I was doing in Bangladesh, video recordings, audio recordings, images, articles. I also go back to my archives a lot as part of my practice. The first twelve minutes of this video are of an underground drag performance in Bangladesh that happened a couple years ago, and there were five performers. One of the performers was murdered with the co-founder of the magazine. His name was Tonoy. So when I looked at the performance—there were five performances, five music numbers—Tonoy was the lead dancer for one of them. I was looking at the video and I was wondering who would kill someone just for dancing? For wearing makeup and having fun? This film uses murder as a lens to look at citizenship, borders, community violence. This film is an imaginary remaking of that performance.

We didn’t have rehearsals, but conceptual sessions with our performers. We asked ourselves what this performer would do in that space, what color of lipstick would this person wear, what costume this person would wear. We would do these elaborate sessions that would lead the script. We really wanted to bring the drag into play. Drag, if you think about it as something people do for pleasure, is something that can cause violence if done in public, people get murdered. So many black trans people in this country are getting killed. Trans people in Bangladesh too. It wasn’t that I was directing the performers; I gave them the idea of the characters, the resource materials I used, the research I’d done, and I asked them how they wanted to onboard in this process. This is how drag works too, you bring yourself into your performance.

When did you film this?

RA: It’s funny—the day we shot was the beginning of lockdown, the beginning of COVID-19. But we had talked about it for such a long time that we did not want to postpone. We went there with hand sanitizer, soap, wipes, and there is a lot of touching in the video. We were literally reminding each other every minute to wash our hands! Don’t touch! A big part of the film is also the makeup process, makeup is how you understand a drag performer’s sensibility. COVID-19 just added another layer of anxiety to this. In that way the film also became a documentary, a documentation of COVID-19 anxiety manifested through the character they were playing at that time. I mean, people will look at it and may not sense the anxiety, but it is there.

I think that’s why the conceptual part of a project is so important to me. I gained a lot of clarity on this project and why I did it.

Someone came into my studio once and asked me whether it was transphobic to have a trans person kill another drag person. I was very critical of my work, discussing with my queer friends who do drag whether any part of my project was transphobic, dragphobic. There is no clear answer. In my eyes it is in no way transphobic, but people might interpret it differently. There is ambiguity in the film’s format.

Do you remember your first experimental film?

RA: I think there is an essence of visual experimentation in all my work, but this program has influenced my thinking a lot since I started here, in terms of my visual experimentation. I often think, as someone who has been so grounded in political activism, there is no ambiguity in my line of thinking. There is complexity, but I know what I’m doing.

What have you been working on during quarantine?

RA: I started working on another fiction project that I find liberating. It’s a folk theatre story, and I think the format will likely be animation. This is also built on the idea of citizenship and displacement and, to a large extent, culinary memory. The entire story is based on the framework of a popular folk story in Bangladesh in which a twelve-year-old girl is forced to marry a twelve-day-old prince. The story is called "Roopbaan"—this became the name of our magazine so the story is very close to me.

What have you thoughts about the classes and instructors at Columbia?

RA: Ron Gregg is a great professor. He gave me a lot of language for the things I was thinking—everything was really educational, really helpful. Shelly Silver has pushed me to think differently. She’s not easy to convince (laughs). I really admire her. Matthew Buckingham, too. Susanna Coffey. This new community I have right now is so inspiring, especially the students. Some of their work is fascinating. I’m pretty much an art outsider. I came from this experience of textile engineering and political activism, but it’s been so nice—I don’t feel so much like an outsider now.

I was undecided between attending a traditional film program or more of an experimental moving image program, and I think I made the best decision to join the visual arts program at Columbia. This is the best program I can imagine. There are people experimenting, performing, sculpting. I’m not limited. Intellectually, it’s so stimulating and inspiring. I think the way I think and the things I want to do are better understood by this community than they would be by a mainstream film program.

Congratulations on being awarded the 2020-21 Davis Putter Scholarship. I understand it’s a scholarship that supports social justice scholars and activists. How do you plan to use it?

RA: I am really honored. The scholarship money will support my education and I am very excited to connect with the Davis Putter community as they will organize multiple convenings for all the recipients of the program. Though the scholarship is not awarded based on immigration status, this is also an opportunity to share that asylum seekers, refugees, and undocumented people are not opportunity-seeking low-skilled immigrants. We are talented, qualified, and equally deserving.