Conversations with Artists in Art Getting Art: Mark Yang '20

Conversations with Artists in Art Getting Art is a bi-weekly series and a play on Jerry Seinfeld's Comedians in Cars Getting Coffee. We interview artists about their art and 'getting art'.

This week we sat down with Mark Yang '20 whose recent works are Father Brother and Me, Sleeping Sitting Nude, and Single Leg.

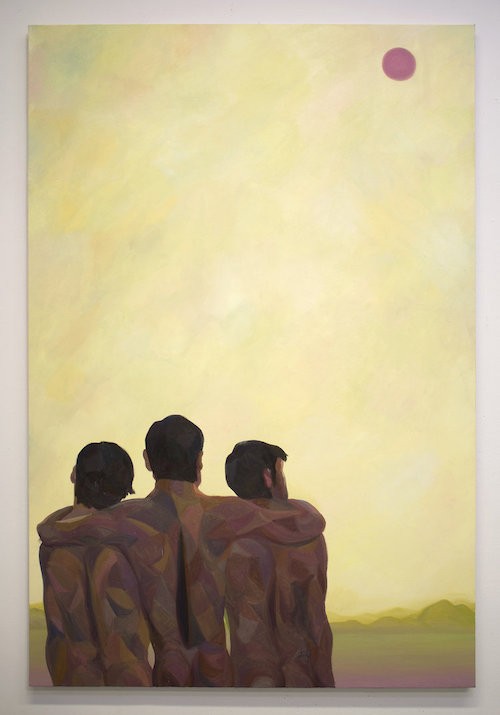

Mark Yang is a second-year visual arts student whose works depict larger-than-life figures standing, leaning, and embracing against multiple horizon lines. Born in South Korea, Yang began his visual arts career in illustration, but after a fateful life drawing, transitioned to figures. His paintings are an interpretation of what it means to live in America as Yang does: as an immigrant, and as a Korean, heterosexual man. In defiance of the male gaze, Yang’s recent works, which show nude Asian men holding hands, touching, embracing, question what masculinity can look like in the 21st century. With shocking colors and gorgeous lines, his figures do not present nudity so much as they embody it, fully, confidently, and with awesome triumph. The objectification of bodies male or female, says Yang, is not something he is interested in—what interests him is how these bodies can be intimate with each other without being eroticized.

In this interview, Yang discusses the MFA program at Columbia, what it’s like being one of few men of color in his year, the practices of painting men, and wrestling.

Let’s talk about what’s on these walls. Long limbs, male limbs, multiple horizon lines. Would it be wrong to say you draw inspiration from Matisse?

Mark Yang: No, not at all. This is a painting I did, in 2017—these were all very Matisse-like. The lines, the fluidity, composition, space. This is like, Matisse plus K-pop.

Where’s the K-pop element?

MY: Their gestures, their hand signs. This K-pop dance move, you see. It’s like a religious painting. You get all those Old Masters’ paintings, you see all these hand signs, all these gestures that kind of symbolize something? Most people wouldn’t know now, but back then, people knew what these symbols meant.

I like that: “K-pop plus Matisse.” What drew you to this interface? How did one artistic practice inform the other?

MY: I mean, yeah. I’m a Korean man. I’m a Korean, heterosexual man, living in America, an immigrant, so I’m always thinking about my culture and where I’m coming from, but then I’m also thinking about my interests, artists I like, Matisse. I’m more interested in Picasso than Matisse, actually. Kerry James Marshall, all these artists I’m thinking about all the time, especially the Old Masters, like Rubens. Peter Paul Rubens.

When did you start drawing these figures? And did you start with drawing figures, or did you start with landscapes?

MY: You know—my first time drawing figures—I mean, you always draw figures I guess. When you start drawing, when you’re a kid, you draw faces, stick figures. We’re all drawn to that: figures. But I guess my interest in figures really started with life drawing. Life drawing, also called figure drawing, is when nude models stand, pose, and you’re drawing from it. The first time I encountered that was college, so 2013, in my undergrad, in Pasadena. It’s called the Art Center College for Design. That was when I first started thinking about the difference between nakedness and nude. Because this is something taboo—it is a taboo. What is nude? What is nakedness? And when models are posing, are they naked or are they nude? And what’s the difference? What makes it different? I started thinking about that, the difference between that, and I think that’s what really drew me to figures.

How do you feel about the arts school program right now? Giving yourself homework, and all that? The independence of it all can be daunting. Does the task of giving yourself work make the art more or less enjoyable?

MY: Sometimes it’s great, sometimes it’s miserable. Actually, I take that back. Last year it was miserable. When I first got here, I had no idea what I was doing. I was getting used to Columbia, to New York, being a stranger, being one of few men of color in my year.

You’re kidding. Really?

MY: There are nine men in my year, but I’m one of the few of color. It’s like—I love them, it’s just interesting that—this was my first time feeling like a minority. It’s my first time experiencing that, even though I lived in LA. When I got here, I was the only Asian man. I’ve never experienced that. And I’m fine with that. I like it, actually. That’s why I left LA, to be isolated.

Is it safe to say that the men you draw here are all Asian?

MY: Yeah, they’re all Asian.

And they’re all naked!

MY: They’re all nude. I mean, it’s something you can think about: naked or nude. When you think about nakedness, there’s something embarrassing or shameful about it. But then nude is more artistic. It’s an artistic term, more graceful. I mean, these men—they’re not embarrassed. They don’t look embarrassed, you know.

How did you arrive at the subject of painting nude men?

MY: That’s a question I get all the time. First of all, there aren’t many paintings of nude men, nude Asian men, period. I don’t think there really is—I don’t think it’s been done, and painted by Asian people in general. It started two years ago, three years ago. Around there. I was typing “nude” into Google and when you do that, most of the images that come up are of women, nude women. And it brought me to a realization. We’re living in a society where we prefer, we normalize nudity in women, but not men. And also when you actually see a nude man, or semi-nude, posing, many people would think this is a gay magazine. That raised a question for me: we’re living in a society where nude women, we don’t think of eroticism, we think it’s normal. But when you see nude men—the mind goes straight to homoeroticism. It varies from culture to culture, of course, but in America right now, this seems to be the case. When women hold hands on the street, it seems to be more acceptable. But when men hold hands, we think immediately that they’re a gay couple. Why is that? Why can’t intimacy exist between men?

I mean, that sunset painting, for example. I guess those men are pretty intimate, looking at the sunset, their arms around each other. But can’t they just be friends? Couldn’t that just be a painting of friends? Because that painting was actually a painting of my family, my dad, and my brother, and me. But this one guy literally came in and said “These three gay guys,” and I was like, “What makes you think that they’re gay? Just because they’re nude?”

That’s true. In terms of being intimate with friends, our movements are pretty stifled. The lines between friendship and romance—they aren’t hard and fast, but they’re there, and there is always a boundary. Being naked or nude is like a final frontier.

MY: That’s a question I’ve been thinking about a lot. I mean, that’s not the only reason I make these paintings. As a man living in a man’s body that has a lot of relationships with other male bodies—friends’ bodies—I’m coming from a culture where men are very intimate with each other. I grew up going to the sauna with my friends. Saunas: we’d take baths together. This is Asian culture. I shared a bed, I shared a room and a bed with my brother, all my childhood, until he went to college. We’re always half-naked, and we shared the same bed and blanket. I grew up in that culture. That’s why I never really had that feeling of strangeness with nudity toward other men. Because it just never occurred to me that the naked man was a homoerotic figure or whatever. It seemed normal to me. But once I started making these kinds of paintings, I found that people were responding: “Oh, these are homo paintings,” just because they’re men. And I think about that. I think about what other people think about when they see my paintings. My work’s been changing a lot too. Meaning back then, my works were a lot more intimate, just like a year ago. Much more intimate with each other. I was too caught up in that idea. I was like, oh, I’m going to show this male intimacy, like platonic friendship. How to be together as human beings. But I’m more interested right now in composition and colors.

So now you’re moving more towards these compositional paintings?

MY: Yeah, these wrestling images. I was actually a wrestler in high school.

No way! So was I. Just kidding. I wasn’t.

MY: Columbia was the first college to have a wrestling team in the nation. And I saw a wrestling match accidentally—I was at Dodge Fitness Center—and I happened to see a wrestling match there, and I was like oh my god! It brought all my memories back. I was like: I need to paint this. There is obviously a lot of male intimacy in this sport. It’s a very intimate sport. Some people really look at it as homoerotic, but it’s a sport. It’s a sport that has happened since Greeks and Romans. Back in those days, they literally wrestled nude, but now they wear these tights. But they used to be nude, outdoors. And that was what it meant to be a man, back in the day.

Like the statue of David by Michelangelo.

MY: The idealized nude man. And that all really changed in modernism. Starting with Matisse and Picasso, they only painted women. They painted some men, but most of their subjects were female. You know most men, the first thing they draw, most heterosexual men—is their fantasy woman. Sexualizing women, objectifying women. It begins at a young age. And I guess that’s why I stopped painting women. I don’t want that conversation. But now that I’m starting to paint men, the conversation is “Are you gay?” They don’t always ask that. But they will question my identity.

Does it frustrate you?

MY: No. I think it’s interesting. I think it’s interesting that if I paint a woman, people will be like, “Why are you objectifying women?” And if I’m painting men, the question becomes “Why are you painting men if you’re straight?” It made more sense to me to paint men. I’m a male, in a man’s body. I feel like all painting is, is painting yourself. These are like personal diaries.

Tell us about your studies at Columbia Is there a particular class you’ve really enjoyed? Have you had any helpful or inspiring mentors or professors?

MY: The mentor program here is really one of the things that makes Columbia, Columbia. I don’t think any other program does this. Once a semester, we take a week off to spend time with our mentor. We don’t go to class. Five days. Kiki Smith is one of my mentors. She doesn’t do it by herself; she does it with Craig Zammiello. The mentor week is whatever they want to do. Kiki took us to a coin foundry, where they sell coins. She’s a printmaker, and I never thought about coins as a form of printmaking. We looked at all these coins, for ages and ages: art through coins. We went to upstate New York to see this foundry she uses where she gets bronze sculptures made. Things like that. My other mentor is David Humphrey. He’s more of a painter, and he takes us to art galleries.

How about your favorite professors?

MY: Gregory Amenoff. He’s the head of the painting discipline. He’s the one who interviewed me for this program, the one who picked me. He’s someone I rely a lot on at Columbia. He’s been teaching here since the nineties. I didn’t know, then, but during the interview, I realized: Columbia was the most welcoming. I felt like I was home. Sometimes during an interview, interviewers try to be above you, but Gregory wasn’t like that. He was casual, you know? We talked about work, but he didn’t try to act like he was above me. And he’s a great professor. He really cares about his students. I can text him anytime and he will come to my studio and talk. Really, he does that. I had some questions about art pricing, and I called him. I love professors who can talk about the realistic part of making art. How much should I sell my paintings for? He’ll be real with you. My work has changed tremendously because of him.

Are the men you draw based on anyone? Because these men have nice butts.

MY: (Laughs.) People say that, but it’s literally just a circle.

I guess that’s what makes a butt nice.

MY: A circular butt? I mean, the art that has the nicest butts, people say, would be Greek and Roman sculptures. And they’re not circular. Those butts are muscular, like round squares. (Laughs.) But mine are just circles.

So you’re trying to draw an unrealistic butt.

MY: No, it’s more like a stereotypical butt. I’m really thinking abstractly, about shapes, and size variations. I’m more interested in that right now: shapes, composition, color, lines, the figures, the ground, figure-ground ambiguity.

Image Carousel with 3 slides

A carousel is a rotating set of images. Use the previous and next buttons to change the displayed slide

-

Slide 1: 'Sleeping Sitting Nude' by Mark Yang, courtesy of artist

-

Slide 2: 'Single Leg' by Mark Yang, courtesy of artist

-

Slide 3: 'Father Brother and Me' by Mark Yang, courtesy of artist

'Sleeping Sitting Nude' by Mark Yang, courtesy of artist

'Single Leg' by Mark Yang, courtesy of artist

'Father Brother and Me' by Mark Yang, courtesy of artist