Conversations with Artists in Art Getting Art: Kevin Claiborne II '21

Conversations with Artists in Art Getting Art is a bi-weekly series and a play on Jerry Seinfeld's Comedians in Cars Getting Coffee. We interview artists about their art and 'getting art'.

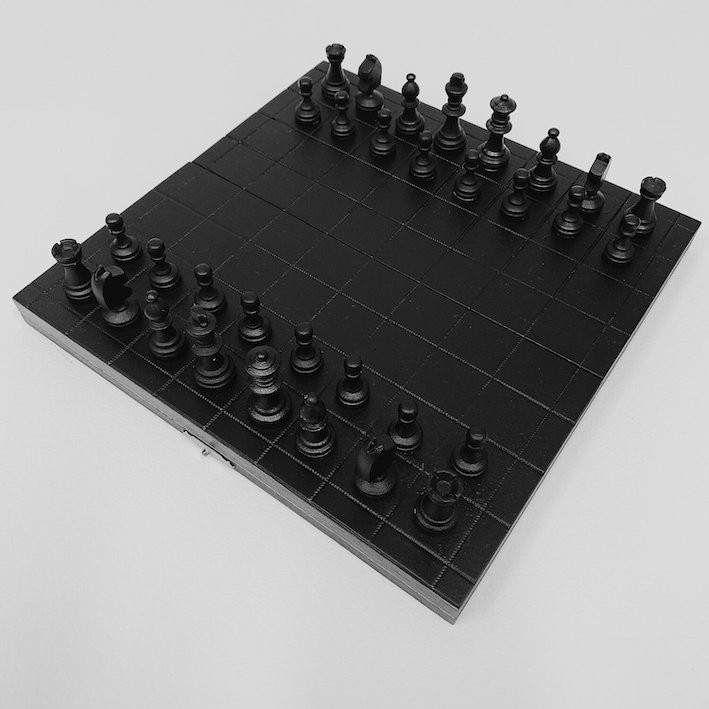

Upon first glance, Kevin Claiborne II’s '21 visual work feels finite. Part of this feeling is due to the fact that most of his work is in black and white: his photography, his sculptures, his portraits—black and white is an easy contrast. But much can be done when color is removed. For one, in Claiborne’s work, the removal of conventional colors magnifies the absence. How does absence function as a tool in art? For example, in two games where colors matter—in a Rubik’s Cube, in chess—Clairborne’s removal of colors by painting over the cube and chess set in black does not simplify the game. Rather it complicates it, and infuriatingly so. The two objects (Sculpture?) transform into useless objects capable only of empty gestures. This is a metaphor, says Claiborne, for the futility of a racially “color-blind” perspective.

Kevin Claiborne II is a first-year graduate student at Columbia University’s School of the Arts. In this conversation, we talk about math, art backgrounds, and voids.

Could you just state your name and concentration for me?

Kevin Claiborne II: I am Kevin Claiborne, I’m a first-year master’s student at Columbia University, and I came in under photography.

I see. You say “came in.” Does this imply you’re doing something else now? Do most students “come in” under some concentration and then move on to something new?

KC: I was accepted by the photo concentration. There are four of us, total. And the portfolio I submitted was my photography portfolio. But I also use painting, poetry, and recently I’ve been getting into sculpture. Or rather, just working with objects.

Are you veering away from photography? Are you working with photography in a different way now?

KC: I’m still working with photography, but while I’m in this program I’m trying to experiment with other mediums, to challenge myself and find other ways of communicating.

What are you trying to communicate? What values do you have in your art?

KC: I think a lot of the art I create, one: I’m creating it for myself, and I view it both as a weapon and as armor. I’m trying to communicate things I’m concerned about regarding race, mental health, identity, and how those things intersect with one’s environment and social conditioning. So, that’s the project.

So initially, you felt that photography was the best way to communicate these concerns?

KC: I think photography is an interesting medium to use to share information. Images can say a lot more than words, but they can also be interpreted in many ways based on context and whatever the viewer has in mind and whatever is going on in society while the images are being viewed. I think photography is an interesting tool that plays with perspective and time. It’s a time-based medium and I’m interested in not only social issues but how social issues are talked about and how they shift and manifest over time. Photography is a play on that. Film photography in particular, because it slows me down, physically, and it’s a very hands-on process.

Not like iPhones and stuff.

KC: iPhones are nice, but sometimes, being able to shoot higher quantities in a less amount of time affects my quality. That’s not true for everyone, but for me, I end up shooting differently when I use my digital cameras. So sometimes I’ll have experiments where I’ll shoot something only with a phone, or I’ll see what I come up with using a digital camera, or on film, and it’s usually a different perspective each time, because I’m using a different medium, using a different tool. I think every tool has a use. Like a best use.

What you said earlier, about photography as a weapon and as armor, that reminds me of something Susan Sontag wrote. She wrote On Photography, and I believe she likened cameras to guns in the way both are tools used to immortalize—take life away—from people.

KC: I’ve heard of that, yeah. I think some people look at photography as a way of capturing moments, capturing people. It reminds them of death because of the sort of—taking a photograph is essentially taking a moment out of a moment, and it brings to mind sort of the temporary nature of everything, including people’s lives. That’s probably what they think about it.

What do you think about it?

KC: Well, some of the work I’ve been doing recently is about death, and I think I see why people can think that. This picture, for example.

Who’s that in the photos, lying on the ground? (Image right)

KC: That’s me. So recently I did a series on this—I’ve been thinking about my own inevitable death, and what it would look like, where it would happen, how it would occur. And if it happened in a public setting, in a city. What would the situation be? How would the body be positioned and perceived and avoided? That’s a self-portrait series. It also leaves out a lot of information, so my skin color, hair—they’re not shown. The narrative isn’t immediately identifiable, but people can put their own stories onto the image. Some of them are half cropped away to give this “looking away” feel. There’s also a performative aspect to me doing this sort of rehearsal or reenactment of my own death.

Was this easy to shoot?

KC: Trick question. Technically it’s easy. Mentally, maybe not.

What’s the name of this series?

KC: It’s untitled, but it has a subtitle I’m working with. And it’s A Void. It’s a play on the phonetics between the word “avoid” and “void.” And there are many definitions for what a void is. A hollow space, something missing, or some type of absence. Or even in cards, a void is when the cards you are dealt are missing a certain suit. For instance, if you’re dealt a pack of cards and you don’t have spades. That is called a void.

Void. A void. It’s also the title of a French novel by George Perec in which he doesn’t use the letter “e.”

KC: And it’s been translated into so many other languages, and other people try to continue to not use a letter.

So now you’re working on a series of photographs in which you are dead. That’s quite sad.

KC: It is kind of sad. I mean, it can bring up discussions about police brutality, the way the Black body has been treated in society, particularly in urban settings. Themes of depression and loneliness and abandonment. Those were all things I was thinking about when I shot this.

Who you are? Who are you?

KC: What a curious question.

And it will be curious to me how you answer.

KC: I think I’m a helper. I like to consider myself a helper, and a thinker, and a doer. Who am I? Such a deep question.

I’ve thought about it a lot though, especially when I’m doing work related to death, and thinking about legacy. Who is anyone? How are people remembered? You remember impact. You remember what they did. Usually those two things are the measurements of who people are. So with me, I don’t know.

Because you described yourself as a helper when I asked you who you were, now I’m going to ask you a question about yourself where I thought you would answer first: where were you born?

KC: Andrews Air Force Base. It’s in Maryland, near D.C.

How did you like that place?

KC: Maryland is nice. D.C. is nice. That’s where home is.

Is it still home?

KC: No. My mom lives in Maryland, my dad lives in D.C. I went to a HBCU in North Carolina, North Carolina Central State University, for undergrad, and I studied math. And I worked at college as a diversity coordinator for a while. I went to graduate school at Syracuse University and got a master’s in higher education administration. I also worked in California for a bit as well at UC Santa Barbara as an adviser for student leadership programs.

It seems you were pretty involved with student life.

KC: Yeah, I like working with college students a lot. After working as a diversity coordinator, it got me interested in working more with students about identity development and professional development. I’m still interested in that. Working with college students of all ages and all backgrounds was something I found fascinating because no two days of work were the same. I liked the unpredictability of working with people who are studying and also learning themselves.

Are you good at math?

KC: Sometimes. It’s hard. But I find it interesting. This book is also interesting, The Mathematics of Art. I’m interested in patterns, particularly in people and in nature. And when you are able to identify patterns you can understand things a little bit easier. I’m also interested in sociology as well, and how people sort of discover themselves and change over time. A lot of the work I do is related to time and also narrative and how historical narratives are changed over time depending on when it’s being told, and who’s listening. Some of the -isms, particularly racism, I think about how they manifest differently over time, and the ideologies people have over time. Like this chess set I have painted, I was thinking whether white has an advantage by going first in chess. And it does. And at higher levels of chess play, the advantage increases. But then I started to think that a colorblind ideology in regards to race is something that makes sense. Like people who say “I don’t see color” think that absolves them of any racism. How foolish that is.

I made this chess set [image to the right] to visualize that the colorblind sort of thought process doesn’t make sense. Particularly in a game as complex as chess, how confusing it gets when it’s all black. You forget whose side you’re on, and sides, duality, disappears completely. And mathematically, chess is one of those few games that is yet to be solved. Like you can solve a Rubik’s Cube. You can solve checkers by forcing a draw. But the number of combinations in a potential chess match is half the number of atoms in the universe. So to play this out with computers, to play out all the possibilities, would take so long. I think about how some of our most complex issues in society, the factors involved in solving them are people and time. So like, if you wanted to get rid of racism, how much time would that require? And would it be possible to get rid of racism if people are the problem?

Nothing frustrates me more than a person who insists they don’t see color.

KC: It’s frustrating. But it’s also well-intended, usually. But is has negative impacts.

I really liked the way you described the chess set. It is a great metaphor for showing the harm of racial colorblindness. How did you first begin taking these kinds of photographs?

KC: I don’t know. People ask me this question and I can’t really pinpoint a moment when I first had an interest in photography. I just remember seeing other people taking pictures and picked up a camera one day. I don’t really know when I got serious. Maybe in the last five or six years. It was a hobby at first, and I taught myself how to do it. Then I started to have more fun with it, and ended up shooting on film rather than digital.

What would you photograph, initially?

KC: Maybe people, travels, random things I observed. Street photography. Broadly that’s the name of the category. I enjoyed doing it the most in New York City. I feel the people and the scenery is interesting. New York is so diverse. People look like they’re going somewhere all the time. People don’t smile, don’t make eye contact. Sometimes I’ll challenge myself and try to photograph the first person I see smiling. Or I’ll count how many people are smiling.

That might be the pattern-noticing habit from math kicking in.

KC: Maybe. I think everybody does that.

Which now reminds me of something David Foster Wallace said, about the creepy novelist or artist who always stares at people.

KC: Yeah. We do.

What are you working on now?

KC: I’m not sure. I think I want to make a bigger version of this chess set and bring it to a public space. Also more of these painting-drawings, putting more of my poetry in paintings. Working at a larger scale with my drawings.

How do you incorporate your poetry into your art? Am I wrong? I don’t see any text.

KC: It’s upside down. Usually under layers of paint. I like to experiment with legibility and using material that has this sort of iridescent quality, where different angles render different levels of legibility. This one says “we have been dying all our lives.” It also says “all our lives matter.” That’s a sort of politically charged two sentences merging into one.

Can you talk to me about your classes so far?

KC: I’m taking art history with artists from the African diaspora with Kellie Jones. And I’m taking a course on methodologies with Tyler Coburn. Those are the only two electives I’m taking, in addition to the two MFA courses.

What’s methodologies about?

KC: We talk about different methods of making and defining art. It’s a great class. A lot of reading. And a lot of good conversations, at the least. The other requirements are the visual art lecture series, the studio visits. I TA for Photography II with Alex Strada.

You get to work with students again.

KC: I like being a TA. Tomorrow I have a studio visit with Susanna Coffey.

How do you like the program so far?

KC: I like the program. I feel they send out a lot of information at the last minute. But there’s a ton of resources. Good people. Good classmates. They’re super talented, it’s scary. My cohort mates are awesome. The conversations I’ve had with people are really awesome. I really appreciate group critiques, because sitting down with people who work very, very differently than I do and hearing their input is helpful. Just to have different perspectives, and see things in your work. It’s also helpful to hear from people who just have more of an art background too, because I don’t have that.

What would you say an art background is?

KC: People who have been in and around the Art world, capital A. Just those who have a different sort of vocabulary around work, and strategy, and methods. So group critiques have been helpful in articulating ideas. I’m not the best when it comes to art words, how a thing feels or sounds. That’s why I take pictures.