Writers in Collaboration: How to Call Your Ancestors into Song

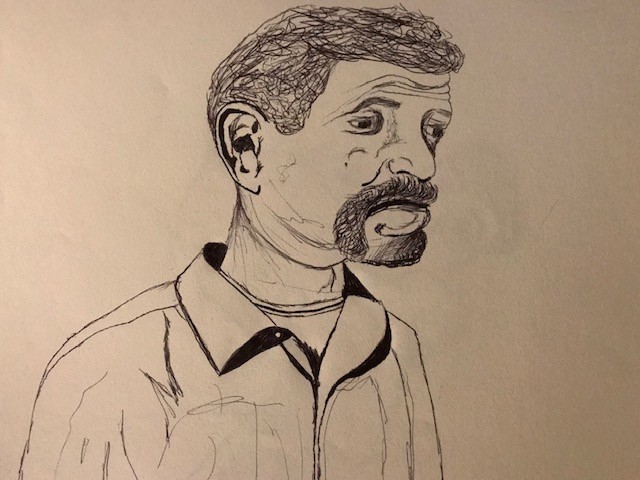

Writers in Collaboration is a monthly series covering writers involved in two art mediums and/or working with other artists. This week we sat down with current poetry student, Mark Gregory Lopez whose thesis is a multimedia book using visual art, poetry, and prose.

Crossing genres is very natural for Mark Gregory Lopez, who began his artistic career with drawing and painting. “Visual art has always been in conversation with everything that I do,” Lopez tells me during our discussion.

“For me it’s all visual in terms of lexicon, language…It all comes from the same place.” If he can’t access an image, drawing or painting may help him find an entryway into a poem. “If it comes out in a drawing, I will still feel that same sense of release as if I had written a poem.” It just needed a different medium to be born into.

His current project, a multimedia book tentatively called Josepha for his grandmother also celebrates the community and culture he grew up in. Using archival material, visual art, poetry, prose, photography, documentation, such as marriage and death certificates, as well as transcripts of interviews with family members and friends, Lopez envisions an “all-encompassing artifact.”

“In Latin culture,” he tells me, “if you want to keep someone alive, you must name them.” Of Mexican descent, Lopez explains that this is how you keep the lineage alive, “and lineage is a very important thing in my culture,” he says. There is conviction and urgency in his voice as we talk about his latest project one warm October day outside Dodge.

“This book began the night my grandmother died when I was 14. My very first poem was a poem I wrote to her the night she passed. I read it to everyone who was there. But then, in church, I put it in her coffin. Everyone was saying why don’t you make a copy and I thought, no, this is just for her.”

Born in Bishop, Texas, Josepha lived in Corpus Christi (where Lopez grew up) for most of her 79 years until her death in 2002. The book is as deeply rooted in Texan history and landscape as it is in character and community. Texas is literally part of the book’s structure, part of the architecture that holds it up; the book is anchored by poems Lopez wrote of some of the numerous natural disasters that have ravaged the state throughout its history.

Each of its five subsections starts with a disaster poem. “I’m not comparing her to a hurricane, or a flood. But [just] in terms of the sentiment of something lost that cannot be recovered, something that affected an entire community, a group of people, not just my immediate family, it packed a serious punch.” When he first ordered the book, the disasters were arranged chronologically, beginning with the 1900 Galveston Hurricane. But the project is based on memory and “you do not order your memories,” so anything chronological was dispensed with.

Instead, 10 poems preface certain themes that emerged, like the theme of water, or flooding, fire or heat. There are images embedded within the poems that he was guided by. "Birth in the Water" deals with the idea that birth is death and death is birth, the idea of entrance and exit. “How does someone enter the world vs. leave this world and what does that mean in terms of a life lived?” Lopez began questioning among other things, his own mortality.

Water imagery is very important to him. “Corpus Christi is an oceanside town, and although my father taught all his children how to swim when we were very young, and I love the water, love being immersed in water, I kept seeing people struggling in water; I’m terrified of drowning.” No wonder, as Corpus Christi was declared a federal disaster area because of flooding at least 18 times.

The images for heat and fire get tied back to his own personal experiences. “When my grandfather heard that you had an earache, he would make you lie down, light a cigarette and stick the filter in your ear. This drew the pain out.”

Using color, the often violent imagery of the culture like the crucifixion, the idea of pushing yourself to emotional extremes in order to find revelation, all this is available for Lopez to draw on. So, too, is how the dead live through us. “In Latin culture too, you honor your dead as if they didn’t go anywhere…I see my grandmother in little things, like how my aunt moves…People live on in mannerisms, movements…”

This semester, Lopez is involved in the Special Projects workshop which embraces more experimental projects. He’s been busy sequencing his manuscript, deciding how the visuals and the words look on the page side by side, how they will flow. “It was hard to sequence the poems to find the underlying narrative. I found that if there was a question I asked in one poem, if in another poem I answered it, I knew that I did not want those poems side by side—I did not want the question resolved too quickly. I want the book to ebb and flow, to have this emotional connection permeate the whole thing.”

There have also been times when Lopez has written a poem and then drawn an image over it. “Both mediums are used, yes, but for me this is a process of erasure where I drew over it so you wouldn’t be able to read the whole poem…because the poem was dealing with something that I didn’t want to be immediately apparent to the reader, where I thought the drawing was probably the most important part. The most important thing for me in terms of a reader, is that someone sees it, not so much that they understand it.”

Surprisingly, the portrait of his grandmother that will be used for the cover of Josepha is by his cousin. Lopez himself has never rendered her. “I still want to,” he says. But, “the entry point is not there yet, and I don’t want to force it.” He is very centered on what he needs artistically, what his “emotional register” is, and won’t be pressured. “I’m not ready to physically conjure her at this point. I’m OK with speaking with her, but drawing her I’m not at that point where I can sit down with a photo of her and draw it, it’s just not the right time.”

Lopez took his first art classes in high school from “the best art teacher,” he says, Tony Armadillo, who still runs KSpace, a community-based program for Corpus Christi youth. Lopez entered college as an art major, but disenchanted with the program, he changed majors, getting a BA in English and a BA in Journalism from the University of Texas at Austin. He wanted to try all kinds of writing and has worked as a journalist during his career.

He is quite frank that writing poetry is not exactly an enjoyable experience. For him, it comes out of pain. “I’m not going to overanalyze the good things. If I am happy and in love I’m not going to sit down and write a poem about it. My emotional compass only points to the bad when it comes to poetry,” he says with a laugh.

“Right now, this book is what is absorbing me.” He admits writing about a family member can be tricky. “I know there are some uncles who are going to question certain things. I mean Josepha was their mother. But I can just hear them saying, ‘What is this about—cutting out mother’s heart?’‘’ he mimics, changing the register of his voice. “There is some pressure in portraying her truthfully—I didn’t say accurately, but truthfully.”

“There is a section of the book where I specifically address my grandmother—it’s just from me to her. And I’m telling her that I’ve never dreamed about you since you left. Maybe that’s what this book is doing. Maybe this is my attempt to dream you.”

Just like the young man who sent his grandmother off to the underworld with a poem, he will listen as the dead try to send one back to him.

Image Carousel with 4 slides

A carousel is a rotating set of images. Use the previous and next buttons to change the displayed slide

-

Slide 1: 'Birth in Water' by Mark Gregory Lopez

-

Slide 2: 'A Pa' by Mark Gregory Lopez

-

Slide 3: 'In the Bathroom' by Mark Gregory Lopez

-

Slide 4: 'Mockingbird' by Mark Gregory Lopez

'Birth in Water' by Mark Gregory Lopez

'A Pa' by Mark Gregory Lopez

'In the Bathroom' by Mark Gregory Lopez

'Mockingbird' by Mark Gregory Lopez