Uncovering the Heritage Silhouette: Juan Hernandez '21

Uncovering the Heritage Silhouette is a bi-weekly series diving into how tradition influences the creation of art. We interview artists heavily influenced by their heritage.

Student Juan Hernandez explores the potential of found objects to reveal underlying psychological connections—such as intimacy, memory, or segregation—inherent to the way we dwell in our domestic and urban environments. His most recent work considers objects as poetic symbols that make part of a precariously balanced system on the verge of collapse. Born in Bogotá, Colombia, Hernández studied architecture at the Universidad de Los Andes, where he graduated Summa Cum Laude. In his work, he reflects on the human relationship with natural surroundings, looking for the poetics that may result from re-contextualizing and juxtaposing his unfamiliar objects into natural landscapes.

What is cultural heritage to you?

Juan Hernandez: Wow, I will need to think about this for a bit. First, I’m from Bogotá, Columbia. The phrase cultural heritage is a compound phrase. If I go for heritage it’s the received legacy that comes from other generations and continues through me. It is something continuously built, written and overwritten, a palimpsest. The cultural aspects make me think beyond a family heritage into the society and community. It makes me think that each person is constantly building their own cultural heritage too as you continue to live and interact with others. For example, me going to Columbia University and meeting everyone here is a way that expands the cultural heritage that I have.

How have you been since the school shut down last Spring?

JH: Right now I’m back at Columbia University. We have just gotten our studios back after seven months! These past seven months were a time to put everything on a hold and I spent time with introspection, developing ideas. Right when lockdown happened, nothing was clear and everything was seemingly getting worse, I started a sewing project with tangerine peels. The making of the tangerine umbrella was very meditative because sewing is a very repetitive action. It was very time consuming and during a time I needed self-motivation.

After that I started reflecting a lot, I wanted to continue developing ideas while not practicing them at the moment. That is why I started a lot of drawing and writing. In this way, I was able to continue developing the many ideas I had at the beginning of the year. Now that I’m back, I have returned to the job of translating them into space and material.

Tell me about your journey to Columbia University.

JH: I have a background in architecture. Because of this I was allowed to design and build projects once I came to Columbia.

But at some point, I realized that I wasn’t attracted to the professional practice of it despite loving studying it. I was more interested in the classes I took as a fine arts minor. The act of making and doing things with my hands in relation to having a critical perspective of the world, like questioning my surroundings, was where my passions laid.

When I was deciding to make a professional career I put the two up against each other and chose arts. I got my first studio in 2015. It was located in the capital city of Colombia. It’s a big city, crowded city, with many layers. I then started working as an art assistant on a sculpture project but this became very time-consuming. I wanted to start developing my own works, my own thoughts and processes. That was when I realized that I needed to go to grad school. I needed to grow as an artist with formal education. I became a full-time artist.

What are your main interests now in the program?

JH: At Columbia of course I learned the design part, where you learn how to order spaces, also giving form to shapes, and how they relate to the city. And that leads into the second direction, which is the city itself. How cities are planned and lived by humans. Which also relates to the third branch, which is the history of the city: how the city has evolved and its architecture. The fourth one is more technical. Basically you have to figure out how to materialize your vision in the world.

Your piece Desvío a medio camino, which is a line of antique doors that bend as a snake in the middle of a salt flat, “builds to explore the physical segregation in Latin American cities: space where restrictions are set in order to divorce the public from the private, the collective from the individual.” What inspired this piece and how did you choose the topic of segregation of Latin American cities?

JH: This started during my time at São Paulo University. In the house, I lived in during that time I had to pass through almost ten different doors to get to my room. There was an emphasis on security throughout the whole city. The doors were like limits, barriers, and protection from the “other,” from the public space. In the end, it's a materialization of segregation. I used the doors in my art as symbols of division.

It’s the social-cultural differences that separate the people. Many Latin American societies have a pyramid structure and people look to get themselves separated from the other groups. An example would be a specific neighborhood’s wealth.

One large issue is how the real estate companies and developers that mass build buildings without considering their relation to the community for capitalistic reasons. The result of all these barriers is that the land ends up belonging to no one. It’s not welcoming.

You often feature your large-scale projects outdoors in nature, particularly secluded landscapes. They seem like a chain of projects.

JH: Yes. At some point, I was asking myself a lot about the domestic space, the natural environments, and how we own authority over the land. I was trying to see these problems and ideas on a larger scale. I was interested in the human error relationship and interaction.

The first exercise or way to approach those ideas was by taking those objects I was transforming, coming from the familiar to the unfamiliar, and locating them in pristine natural places. This was a series of exploring the tension when looking at these artificially made objects, architectural bodies, amongst lands that have no human presence.

Later on, I collaborated with other artists where we camped at the Northern Andean páramo for ten days. We explored our relationship with the surroundings from being overexposed. This resulted in Gris Que Te Quiro Verde.

I saw that you held an exhibition for that project in Bogotá, Columbia last November! Gris Que Te Quiro Verde roughly translated to “Gray, How I Want You Green.” And I read that it was based off of a Federico Garcia Lorca poem. What was the importance of having this take place in the mountains?

JH: Yes, Lorca has this poem called “Romance Sonámbulo,” which main’s phrase is “Verde due ti quire verde,” which is “Green, how I want you green.” One time in São Paulo I heard someone say the phrase “Gris Que Te Quiro Verde'' and I was struck by how that one color change made such a different image. The gray reflects an industrial city and green as an intense love or desire. It was very relevant when I was up in the mountains because it’s a constantly changing environment. The weather particularly and the fog would make the land gray. It was a reflection of our fleeting feelings also. All of the works in that project are named after green or gray-toned colors.

You came to New York City after this project, how did the environmental change affect your artwork which focuses on many natural environments?

JH: Once I arrived here, at my studio, there were no windows and no interaction with the outside world. It was such a huge contrast as I kept on exploring the relationship with the natural environment. Not having that anymore, I started searching for organic materials to bring into the studio and found objects I already worked with. A lot of the materials I liked were those related to the passage of time, transformation, segregation, nature, and preservation.

I brought a lot of soil, tangerines, salt, and other items into the studio. I’m still exploring how the natural world interacts with the artificial human-made world.

In terms of community, we are fortunate to have a vast internet. Somehow it brings up closer than if one is really abroad. Culturally, for sure the language barrier is a bit of a struggle for me and essentially a cultural barrier. I argue that language has a structure of thought that implies ways of understanding the world, and how you relate things. There is a lot of miscommunication due to mistranslation.

So you grew up in these South African metropolises, and while living in these massive cities, you made the decision to move from architecture to sculpture. Last year you were in a residency nearby the lake Tota. What emerged from that residency?

JH: Yes the lake is the biggest natural lake. It was interesting there, because it was high on the mountains, super cold. The idea was to work with another artist. Another artist and I were invited to complete a project but we thought it would be interesting to embark on the whole project together in the sense of a dialogue. The resulting work was not two different points viewing the same thing, but more like viewing the thing from two different perspectives—it was more about the intersection of our interests and our experiences and our dialogues which would produce the work.

We were interested in—both of us—with the landscape, and our relationship with the landscape. We wanted to understand our relationship to the landscape in different ways. The core question was how humans relate to environments and landscapes. The physical relationship with the environment. We tend to think about landscapes on the horizontal line, and it’s a contemplative relationship, but you think about it, there is also a vertical relationship to landscapes that isn’t always explored. This comes from looking down, and from being aware of where you are. That was one of the things that appeared during our spare time while we were there; we were super aware of the vertical and horizontal landscapes of the environment. The emotional and physical relationship with the landscape become more precise.

A lot of your piece’s titles are in Spanish, which depending on who the viewer is may be a foreign title. Is this due to mistranslation?

JH: Mistranslation does a disservice to the work. I have a written practice that is mixed with different languages and it is intentional. They are typically complete ideas and I usually search for the poetics in the images built in the writing. Despite the many translations of Gris Que Te Quiro Verde, the same ambiguity of the original does not come across. The Spanish is so specific and hard to grasp. English does not bring across the cultural context.

How does this affect your audience?

JH: I’m often asked about my audience in the program. It’s something I question every day. Who am I making the work for and who can understand it better or worse? When I choose my objects I look at certain aesthetics, such as ones that have certain temporality that isn’t necessarily recent. I look for objects that have a history and are archetypical. I try to add as many layers as possible to allow different types of audiences to engage with the work. I want people to see the objects and use their own experiences with those objects to have a new intimate viewpoint. I think in the end I explore universal topics through one identity.

With the first-year show postponed (due to COVID-19), what are you working on now?

JH: Now I’m working on a bigger installation. It’s on objects that are interrelated, like the threads. I want all the objects in the same space, living amongst each other. I think it’s something that I’m developing and in process of. I’m currently building those visual moments that help me create a larger narrative. Since I’m currently developing and transforming each moment, I’m expecting a selection of that to be in that exhibition.

Image Carousel with 9 slides

A carousel is a rotating set of images. Use the previous and next buttons to change the displayed slide

-

Slide 1: 'It's a Matter of Fact'

-

Slide 2: 'It's a Matter of Fact'

-

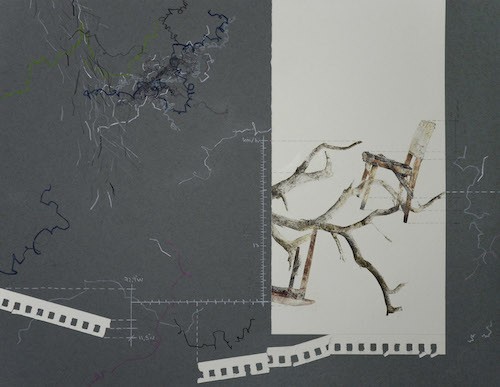

Slide 3: 'Studies'

-

Slide 4: 'Studies'

-

Slide 5: 'Studies'

-

Slide 6: 'Studies'

-

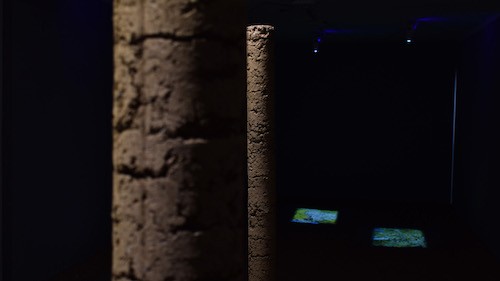

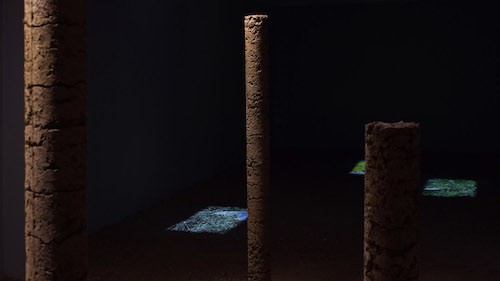

Slide 7: 'Gris Que Te Quiro Verde'

-

Slide 8: 'Gris Que Te Quiro Verde'

-

Slide 9: 'Gris Que Te Quiro Verde'

'It's a Matter of Fact'

'It's a Matter of Fact'

'Studies'

'Studies'

'Studies'

'Studies'

'Gris Que Te Quiro Verde'

'Gris Que Te Quiro Verde'

'Gris Que Te Quiro Verde'