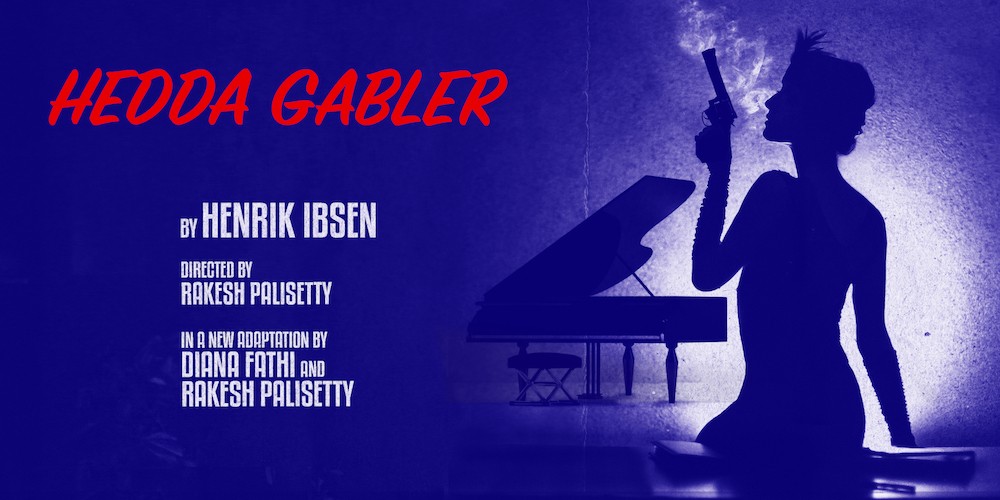

Dream Logic: A New 'Hedda Gabler' in Rakesh Palisetty's MFA Directing Thesis

“I wanted to go deeper than the intellectual mind,” Directing student Rakesh Palisetty said of his thesis production, Hedda Gabler. “Images that stay with you and do something, and you can’t really put your finger on what that is.”

In this new adaptation, co-created with Dramaturgy student Diana Fathi, Palisetty invites the audience to experience an atmospheric, dream-like world, far removed from traditional stagings of the classic play.

Fathi and Palisetty began with a hundred-year-old nearly literal translation of Hedda, and set about cleaning up the language, cutting down long expositional speeches. The result is a crisp, well-paced work, bristling with blunt dialogue, and a new framing device.

Hedda, one of the most iconic characters in the canon, is a woman trapped in an unhappy marriage, in a house and lifestyle she doesn’t want, bound by the strictures of a privileged society that observes her every move.

“She’s performing for society, being this person because she’s afraid of scandal,” Palisetty explained.

In this production, he and Fathi trap Hedda within the play itself.

The stage is bare except for a piano, a pyramidal set of stairs, and a mirrored vanity, crowded with wigs, makeup, glasses and decanters. As the audience filters in, Hedda (Kristina Szilagyi) is seated here, staring into a mirror attached to a camera; an eerie, live grayscale video of Szilagyi’s face is projected across a massive upstage screen. She grimly applies mascara, lipstick; an actor preparing to go on stage, though she is already on stage.

The first spoken lines won’t be found in Henrik Ibsen’s original text; Fathi and Palisetty wrote them for this adaptation: “My name is Hedda Gabler,” Szilagyi intones from her seat, “This is my piano, and these are my guns. This is my life. I am 130 years old, and in less than 90 minutes, I will be dead. Again. In a way, I’m dead already. I’ve lost something.”

Hedda is doomed to perform Hedda again and again.

Even Palisetty was unable to release her. The director said he was interested in changing the ending, and floated the idea that Hedda might not have to kill herself at the end of the play.

“Everybody was like no but she has to kill herself because it’s Hedda Gabler,” he said. “I am at a point where even I, who has all this control over the course of this character’s journey, am not able to change the course of that journey.”

This sort of exchange seems typical of Palisetty’s creative style, which is driven by listening, watching, and experimenting. It is improvisational, intuitive, often devised in collaboration with the cast and creative team.

When cast members dropped out, he had actors double up roles, a fortuitous decision which only adds to the sense of the play’s dream world. One of the most striking visual elements of the production—Hedda’s famous pistols are replaced by her hairpins, and each fateful gunshot is represented by popping a livid red balloon—was similarly a happy accident.

Inspired by an undefined instinct, Palisetty had already brought balloons to rehearsal, when he noticed that Szilagyi frequently played with her hairpins. As he describes, the idea developed from the actor playfully popping balloons on set.

To Palisetty, the immediacy of the pop was far more interesting than any gunshot sound piped in through a loudspeaker. (The decision to not use prop guns seems especially poignant in the wake of the tragic on-set shooting of cinematographer Halyna Hutchins this October.)

The production is full of other haunting images; Hedda, clad in a voluminous fur coat, tearing up the manuscript of her ill-starred one-time love Eilert Lövborg and feverishly consuming the pieces. In another scene, she is pursued to the top of the stairs by the men in her life (the excellent Isaiah Dodo-Williams, Chris Martel, and Riley Austin Scott,) each wearing grotesque baby masks (Hedda, as we’ve learned, is pregnant.)

“I was playing with the idea of this sort of dream logic that does something deeper in your subconscious or unconscious,” Palisetty said. “Images that stay and do things differently to everybody.”

This unsettling Lynchian atmosphere is enhanced by intense performances from each cast member, by their contemporary dress, and by the barrenness of the set. It is, as Palisetty describes, “a world with possibility.”

Fathi, Palisetty, the cast, and creative design team have created a new reflection of Hedda. A figure who flickers in and out of familiarity. She might wear a starlet’s backless gown rather than the corset and stays of her 19th century self, but this Hedda is still trapped in her own world.