Dissolve With the Infinite: 'This Body Is So Impermanent...' Screens at the Rubin Museum

A dissolve effect often appears in films as a transition, a way in and out of scenes, superimposing images to let them speak to each other for a few seconds before we arrive where we’re going. Most films are trying to maneuver us onward, to move us through a story.

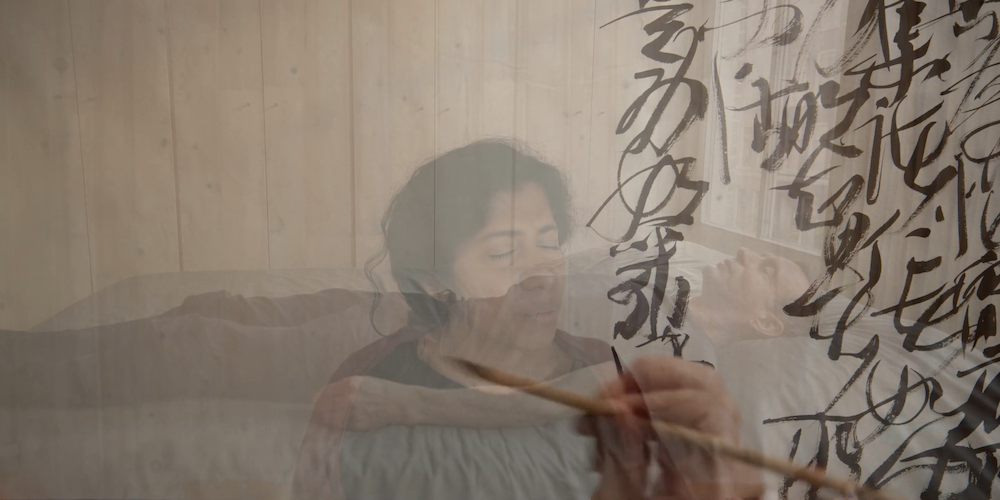

A film with a radically different approach, this body is so impermanent… isn’t trying to move its audience anywhere. Rather it is an invitation to stay, to contemplate, to experience. The use of dissolve transitions—images overlaid for up to thirty seconds, sometimes minutes—is like a visual expression of a meditating mind, holding thoughts in simultaneity, flowing through and returning.

The images are these: the master calligrapher Wang Dongling loops black ink across a continuous sheet; the choreographer Michael Shumacher sweeps his body heavenward; the devotional singer Ganavya, her eyes closed in concentration, pours forth the words of a first century Buddhist teaching. All three artists, working in the same moment from three different time zones, move together through the text of the Vimalakirti Sutra.

When I arrived at the Rubin Museum Theater on February 10, 2023, the film’s director, Peter Sellars, was standing on the stage, addressing all one hundred of us as if we were gathered in his living room.

Sellars was introducing the film, which was to be followed by a panel discussion between himself, Ganavya, School of the Arts Dean Carol Becker, and palliative care physician Doctor Craig Blinderman, Associate Professor of Medicine and Director of the Adult Palliative Medicine Service at Columbia University Medical Center/New-York Presbyterian Hospital.

“The first shots are way too slow, and way too long, and that’s on purpose,” Sellars said with a smile. “The film is only an hour and fifteen minutes, but it feels like many lifetimes. It is intended to slow down your metabolism.

“These are words that the longer you think about them, the more they mean…Please feel free to just give yourself the spaciousness to experience all the things you’re experiencing. Because it’s not a film to tell you something, it’s a film where the teaching is the experience. And the experience is yours.”

The sutra tells of Vimalakirti, a businessman and bodhisattva who has fallen ill. From his deathbed, Vimalakirti imparts to his visitors the experience of his fragile human body and its relation to the infinite. It is a text about illness, mortality, ephemerality, and the body of reality.

In the film’s opening, the thunderous rush of a waterfall is followed by the rhythmic swirl of an inkstone, the rustle of the calligraphy brush, its tail shuffling and flicking. This gives way to a silence in which Ganavya begins to sing Vimalakirti’s first words: “Oh my friends, this body is so impermanent, fragile, unworthy of confidence, and feeble.”

Her voice is like a bird in flight. It is a beating heart in the air, muscled and alive but soaring, carried on invisible currents. With it, she expresses the feeling of each new word. She sings the word ‘feeble’ so that it becomes breathy and diaphanous, gossamer notes, like a trickle of water, or a cobweb in the sun.

She sings the word ‘painful’ in long, flailing vowels, as her image is superimposed with one of Schumacher stretched out on a bed. He contorts with grace and fluidity, but in recognizable attitudes of agony. Ganavya repeats the word—‘painful’—and now ascends into a wail, opening the ‘a’ in pain higher and higher, an anguished cry.

Wang Dongling’s brushwork is similarly interpretive. As Sellars noted, “He is not writing the literal characters. Wang Dongling is moving into an emotional, spiritual radiance and intensity that leaves the words behind, because the Vimalakirti Sutra says explicitly: what we’re talking about cannot be expressed in words.”

Sellars recalled discussing the passages about sickness with Wang Dongling, suggesting, “what about loading the brush with a lot of ink, so we can see the soaking hemorrhage?

“And he said no, I’m doing exactly the opposite. He said, on those sentences that are about the sickness, and what’s unbearable, I let the brush get as dry as possible, so it’s scratching the paper, and is barely able to make an impression.”

In his performance, Schumacher is also a calligrapher; his body is both brush and symbol. According to Sellars, “Michael, seeing Wang Dongling’s calligraphy, said, ‘I want to dance with the tip of his brush.’”

As Ganavya sings about the body of the enlightened Tathagata, Schumacher sweeps his arms into twin curves, poised on one foot, then he bends into a kneeling pose, smooth as a stroke of ink. Sometimes the dissolve effect places his frame over an image of Wang Dongling’s forehead, as if the calligrapher were dreaming of this dancing figure.

In the original conception of the project, these artists intended to tour museums to perform their collaboration, a plan interrupted by the fissure in so many stories: the Covid-19 pandemic. “But then suddenly the text we had chosen had another level of meaning,” Sellars said, “that sickness is a teaching, not just an affliction. And that in fact it’s a spiritual path.”

Throughout the first summer of COVID, Sellars said, the team would meet “starting at three in the afternoon in Hangzhou where Wang Dongling was [working]. Ganavya was in a Sufi chapel outside of Portland at midnight. And Michael Schumacher was dancing in his apartment in Amsterdam at 9am. And the technical people were in New York, at 3am.”

They studied the text together for four months before beginning to perform, and no performance, Sellars recalled, was ever the same twice: “All three artists are improvisatory artists…they kept exploring the material, and the nature of the material is infinite.”

Following the screening, Sellars and Ganavya were joined in a panel discussion by “expert witnesses” Becker and Blinderman.

“I’ve seen the film many times, but I’m in shock seeing it today on this screen,” Becker said. “The sound just vibrates through your whole body.”

According to Becker, the film approximated the experience of watching her own mother’s passing, which she chronicles in her book Losing Helen (Red Hen Press, 2016). “The book is totally about grief, but never an attempt to pull her back, because I understood that the body…had just decided to stop. She wasn’t sick, she was just old. And I watched her release herself from her body.”

As “a practitioner of the Buddha way,” Dr. Blinderman spoke about how he lets his spiritual practice inform his role as a caregiver. “It means deep listening, and presence; looking at my own stuff, and seeing how that can get in the way and separates me; trying to adopt a ‘not knowing’ mindset—which is very important in the Zen tradition.”

Ganavya, when asked about her experience making the film, was silent for a full fifty seconds, a delicious eternity in which the entire audience contracted toward her in total anticipation. When she spoke at last, it could have been a sutra in itself.

She explained that at the time of the project, she had just been in an accident. “I hadn’t moved in a month and a half maybe. Which is why I was living in a chapel…The heater was off, because the heater was too loud. I didn’t take painkillers because I was afraid that I would lose presence, and I needed to be as present as possible to receive everything that Peter was saying.

“‘Friends, this body is so impermanent,’” she quoted, “‘unworthy of confidence, fragile, feeble, insubstantial, perishable, short-lived, painful…subject to change.' I’m sitting here thinking, I’ve just gotten into an accident and [my body is] taking care of me, and this is how I’m going to abuse my body now, I’m going to sing to it, you are unworthy of confidence. Peter, I can’t do that!” she laughed.

But Peter traced for her the etymology of the word confidence, which shares a root with the Latin word for faith. “Then I could sing the words ‘unworthy of confidence.’ What are the things I’m doing to my body? Body, can you have faith in me? Can I have faith in you?

“I had a place to be during the pandemic, even if it was virtual. I had a place to go, a place to study,” Ganavya explained. “I think this is ultimately what we all want in life…to go somewhere and speak about love, in whatever language, or in whatever form. I am grateful that the film exists, but what I’m mostly grateful for [is] the eight months that led up to it, that gave me a way to be, that allowed my longing to turn into a kind of belonging.”

We all fell silent again. Becker braved the microphone to respond to Ganavya: “What you just said explains why every word of the text has this resonance, that there’s so much of you in every word. That’s why it communicates that way.”

Becker especially wanted to appreciate “that incredible [final] image of the waterfall, and the body dissolving into it, which I find brings the whole thing together for me. Tim [Squyres, the film’s editor] had originally made it a very short image, and Peter was the one who said no, longer. No, longer. No, longer. He understood as an artist that that was where people were going to find resolution in the film. That is what one understands when witnessing death—that the elements are all dissolving right in front of you.”

Vimalakirti Sutra, as Dr. Blinderman had suggested earlier, is about “going beyond our small self…going beyond our conceptions of this body, and recognizing that the absolute is mixed into this reality.”

The final image is of Schumacher lying on his side, gradually suffused and replaced with the opening image of the waterfall, the cascade flowing into the valley between hip and shoulder, dissolving the transparencies of the finite together with the infinite.