Conversations with Artists in Art Getting Art: James Mercer '20

Conversations with Artists in Art Getting Art is a bi-weekly series and a play on Jerry Seinfeld's Comedians in Cars Getting Coffee. We interview artists about their art and 'getting art'.

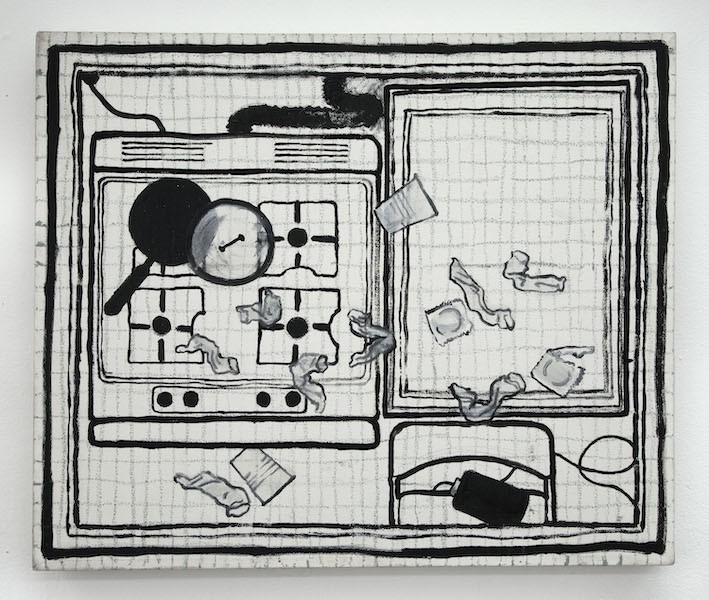

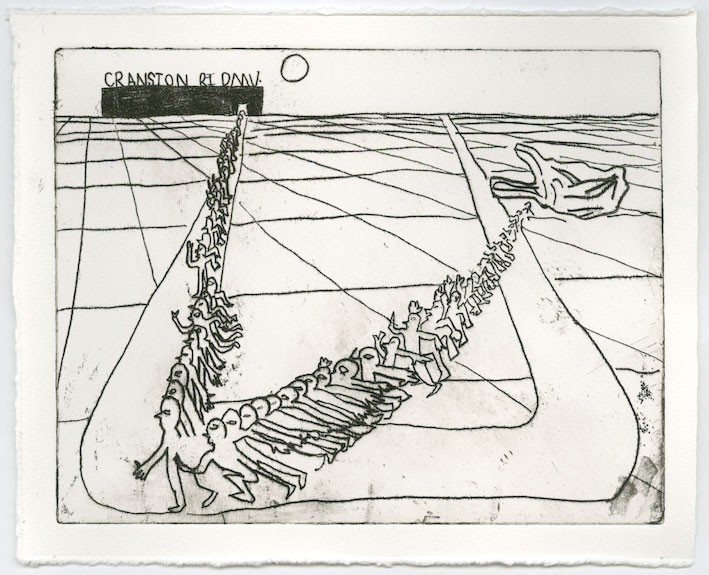

A bike takes a bath; condoms are scattered across the kitchen counter; men walk in sync to the DMV. James Mercer’s '20 drawings are definitely humorous, humor derived primarily from the suggestion of human behavior, rather than images of humans actually behaving this way. In calculus the derivative of a function reveals the function’s sensitivity to change over time; likewise, Mercer’s work, like his bike-in-a-bath—two human-sized objects fitted together—is derivative in the mathematical sense. His work, in their black-and-white, have the appearance of being a simplification of human life, when in fact these cunning grids and sparse images reveal far more.

In this conversation, we talk about life in a gentrifying New York, collaborating on art projects, and the function of language in art.

Looking around your studio, I see lots of paintings, drawings, flat things. Mostly two-dimensional things. Is “visual artist” too broad of a term to call the work that you do?

JM: I don’t think it’s too broad. I try to put very few constraints on myself, and particularly while I’ve been in school, really if I have some sort of impulse or idea that’s sticking in my head, no matter what medium it is, I try to give myself space to do that. It’s just that most of those ideas have been for paintings and drawings.

It’s often an image that will pop into my head that I will become fixated on. I will be thinking about variations on something, for example, this painting of a bike. Imagine it from the side, from all these angles, think about various ways and situations in which I could paint a bike. And what will usually happen is that one idea will be a little bit stickier in my mind, one of them will kind of persist, and I more or less will have to paint it—I kind of don’t have a choice.

You placed a bicycle in a bathtub. Could you take me through the thought process of getting that bicycle into the bathtub?

JM: Here, I was thinking about the placement of the bike. I also have a kind of a persistent interest in objects in spaces that can be stand-ins for a person. A bike and a bathtub are both those, they are both single-person-sized objects. On a very basic level, I ride a bike, and I use my bike every day, so to some extent, not really in any obvious way, but there is a little bit of a way in which the bike is a stand-in for me, or could be. Or at least I identify with it. So I think the image of a bicycle was one persistent idea in my mind, and how I could portray it, and where it could go.

You know, I was excited about the absurdity of that—also the double-figure thing. If you look at the image closely, the scene is a little spare. The tiles on the bathroom floor are kind of cracked, a little bit messed up. And I think part of what was compelling for me was that there might be a sense of abandonment, that you are coming into an empty scene. Having a view from above implies that this scene is truly empty in the sense that the viewer can’t even really be there. You’re looking at the objects from an impossible view, there is no one here.

People are missing in your paintings, which is quite a melancholy feeling. In their place, people-sized objects. What’s the story behind this insistence on grids?

JM: I have some pretty wild philosophical musings about grids that have been going through my head for a while. The idea that a grid is sort of a fundamental organizational structure, and maybe all reduced are being reduced to a single grid, then also living in New York, living in a more or less grid system, which then nests other grids in the form of floor plans of the buildings, the layout of various objects, working on lined paper. If you start counting the number of rectangles in any given room, for example, you realize that it’s enormous.

Standing in this room right now, there’s probably tens of thousands of rectangles in this space. Grids and geometric organizations are everywhere. We’re surviving by them constantly, and I wanted to explore that very simply. It’s such a pervasive form in my life that it was inevitably just coming out in the work. I began by trying to do perfect rectangles, with a ruler, but then I started to feel as though measuring the grids without a ruler, drawing them freehand, so the line kind of wavers, was more evocative of my lived experience in New York, which is that everything is laid out in a very geometric way, but it’s also imperfect. Everything’s so damaged. This room has various dings and dents and stains on it, everything is kind of destroyed by touch.

Why are there condoms on a stovetop?

JM: I was thinking about living in New York, specifically, grids—I was attracted to these weird contrasts between intimate and impersonal, or spaces that are infrastructural and also domestic. The thing about condoms is that they are mass-manufactured objects for totally utilitarian purposes, but they also exist in the most intimate spaces and moments in our lives. There’s something really crazy when you think about them. There’d be this insertion of industry into quite literally the most intimate sexual interpersonal space. Scattering them all over a kitchen, and having a lot of them, implies some kind of weird sexual situation, and I was compelled by this strange dissonance between distance and closeness, and the kind of perverseness of that, and the potential of this to be kind of disgusting.

I guess something about these go back and forth between indifference and intimacy, between geometry and disgust, is that often for me, the thing that breaks the order of the picture is where it actually becomes fun.There is a way in which these images can be disturbing, but there’s also a way in which I find joy in the spaces where order breaks down. There might be something dystopian about them, but that dystopianism is actually a positive thing. That’s actually where I find pleasure in images.

What is happening here [below]?

JM: There’s a bunch of guys coming out of a plastic bag and then going in a line into the Cranston, Rhode Island DMV.

I was thinking it was maybe their life cycle: they leave their plastic bag and then go to the DMV, and then that’s it. When I was living in Providence—I went to RISD—there was this failed retail chain called Apex. The buildings would look really strange, sort of pyramid-shaped buildings, very bizarre. It looked like a ziggurat or something. And the chain store failed, so for a while Providence had its registry of motor vehicles in the abandoned Apex. You would go in and it would be this massive room. It’s like if you took a Dress Barn or a T.J. Maxx and converted it into this single space full of office cubicles where people would go to renew various forms of identification. It was really weird, this funny mix between retail and state institutions. At one point I got a ticket to go to a particular booth to renew my driver’s license, and I got lost on the way, and just ended up in what used to be the men’s section clothing, but there were just piles of discarded coat hangers everywhere. It was very bizarre, it left an impression on me.

From that, I learned you went to RISD.

JM: (Laughs). Which bit of information is more important? We’ll let the readers decide.

How was RISD?

JM: It was great. RISD was just what I needed at the time. I’d been obsessively making artwork for all of high school and before—a lifelong obsession, really. It was great to go there and be able to make. And the school really celebrates that. At least when I was there, they appreciated the people who could just kind of focus and produce a lot of work.

Could that ever be overwhelming, or paralyzing, sometimes, you think?

JM: There were some people who didn’t have as clear of a direction and didn’t know what they wanted as much, and so I remember that time for them could be a little more frustrating. And I’m also of the opinion that it’s sometimes healthy and necessary to be in a little bit of a crisis, and that anyone who doesn’t have crises every so often probably isn’t trying. There’s also a way in which you could have a thing that you’re doing, and get so fixated on the opportunities or other ideas could drift off. I’m of the opinion that sometimes it’s necessary to make that art. School’s a great place for that.

School can be a place for great freedom.

JM: I’d mentioned earlier wanting to give myself a lot of permission while I’m here. If I have an idea, even if it doesn’t seem like a good idea, I will execute it. And that’s something I’ve really appreciated about this program, having the space to do that. I’ve definitely gone down some weird side roads while here. I’ve had to explore things that turned out to be dead ends, because that’s just part of what you have to do, to find out what you really want. I think I’ve narrowed in on some things.

What specific changes have you noticed?

JM: For one thing, I realized how important language is to me. That was something that I wouldn’t have guessed a year or two years ago. I would not have guessed how important the tenets of language would have been for me. When I first got to school, I would make work, and each work would look like it was made by a different person. And only when you saw a lot of them would it seem credible that these were made by the same artist. That, I think, has softened a bit since school. There’s more transactions, there’s more consistency across pieces. I still experience them as being pretty disparate, but it’s narrowed a little. I would attribute that to just having the time to explore the spaces in between works. I’ve made a few works where I think about a literal analogy, kind of like: these two paintings are going to have a baby painting, and I’m going to make a painting that’s halfway between these two paintings. I’ve done that before, and it’s been somewhat productive.

How does language play into your work? What kinds of freedoms do you have to give yourself to allow this element to sink in?

JM: I’m a pretty verbal person on a cognitive level. I’ve always been sensitive to words, and to language. When I came to school, I also had serious questions about the value of art, and how art operates within a larger context, and what it is we want from artwork, either as artists or as consumers of it. And language can be a very clear way of communicating—no one questions whether or not we need language. But people constantly question whether we need art. Bringing text into artwork is a way to think about those kinds of differences, and to think about what an artwork can do, what it can be, what it can mean.

Have you worked in other mediums?

JM: I’ve done a lot of work in animation. I recently did an animation with Yifan Jiang, who’s also in the program, called Two Truth and a Lie. I really love animation. It’s very time consuming so I don’t make them all the time, I’ll do an animation every couple years or so, and there will be long stretches in which I paint and draw.

It was great working with a friend, that was so much fun. Working with another person opens up other possibilities, things that you wouldn’t do. Decisions that you would never make alone may come up in a collaboration, so it will expand what’s possible for you to make, what’s possible to happen in artwork. Ideas I would’ve written off, she would be very enthusiastic about, so it becomes almost like we would dare each other to do wilder and wilder things. Yifan and I really understand each other, and we’re friends, and so we share enough of a vocabulary—we’re also strangely similar as people. Anyway, we share enough of a vocabulary that I think, even though we were daring each other to do these wild things and communicate about them and understand them and process them very well.

That can be rare.

JM: I think so. Particularly in interdisciplinary programs, where people have different backgrounds and different vocabularies. Maybe part of what helped was Yifan and I both have a solid painting and drawing two-dimensional background, and are even similar in our artwork. We’re both very interested in painting. We are both wanting to turn up our commitment to narrative and to storytelling. Having that shared vocabulary enabled us to communicate despite doing weird, counterintuitive things.

You have lived in New York for twelve years now, right? Since 2008. That’s quite a while. I love hearing people’s moving-to-New York stories. What’s yours?

JM: There really was no grand scheme to move to New York. I was in Providence, somewhat drifting, and a friend offered up a room for sublet. So I’ve been here for twelve years, and will be here maybe for life. (Laughs).

How has the city changed for you?

JM: The specter of gentrification has been a much talked-about subject, and it’s—the understanding that you as an artist are part of that problem has been a feature of living in New York since I arrived. It seems like all that’s really changed is the vanguard of gentrification, and what’s already lost territory. I will say there is a kind of disturbing sense that eventually New York will end up like Zurich, where you just have to be rich to exist there. I think this is also said about D.C., which is surrounded by a periphery of poor areas that kind of feed the wealthy center of the city. It’s easy to imagine New York going in that direction, but who knows what tomorrow holds.

Who are some visual artists you admire?

JM: Paul Klee is a heavy hitter for me. Diana Cooper, who teaches here and is a good friend of mine, has had a very big influence on me. I listen to a lot of music, and I think that arguably the influences coming to me from music are more important to me than the visual art. Specifically, Peter Seligman, he’s also a friend of mine. Josephine Halvorson ’07 is someone who has more recently entered my mental space.

What classes are you taking?

JM: This semester, I’m taking Painting III with Rochelle Feinstein, which is great. I’m also taking Sarah Sze’s class, and it’s been really excellent to meet her and have studio visits with her. Before, I’d been mostly taking philosophy classes, specifically David Z Albert’s class, which was excellent, I would highly recommend it to anyone. A totally no-bullshit kind of thinking is required for that class. It really helps to clarify and structure your thoughts. The whole class is about constructing these elaborate very precise ways of thinking. I’d also taken Philip Kitcher’s Classical American Philosophy class, which was really about American pragmatism, also an exceptional class. Not unrelated to David’s science of philosophy class, but maybe with a bit of a more expanded scope. Both of them are great.

There’s a sense of realization with your work, I find. Like the men leaving the bag to enter the DMV, the condoms in the kitchen—things are paired weirdly. What is your intention in doing this?

JM: I like them to be sort of a slow read. I think a lot of people come in and don’t know what they’re seeing, and part of that is by design. I like images where it takes a second to resolve what you’re even seeing. That’s an important method for me. Slowing down recognition. Looking at something familiar and, in such a way, surrendering to the unfamiliar.

Beautifully put.

JM: I’m full of aphorisms. (Laughs). I just hang out here and spout quotes until the sun goes down.