Constructing Futures: Making Ecological Art in a Time of Uncertainty with Alumna Priscilla Aleman

Constructing Futures: Making Ecological Art in a Time of Uncertainty is a biweekly series that features artists who use found materials, natural resources, and the landscape to construct work that addresses the harsh realities of our ecological age.

Alumna Priscilla Aleman ‘19 is an artist working primarily with sculpture and large-scale installations. In her work, she asks questions about the afterlife and memory, place and the natural world.

Aleman is based in Miami and New York. She graduated from The Cooper Union with a BFA in sculpture and received an MFA from Columbia University. Aleman has exhibited in group shows at the Smithsonian American Art Museum, The Margulies Collection, National YoungArts Foundation, among others.

On an unseasonably warm day in November, I met the artist at a coffee shop. Soon, we relocated to Central Park. Upon walking into the park, we saw a dead squirrel in the bike lane. Without missing a beat, Aleman asked me to hold on for a minute. She picked up two sticks and carefully moved the creature under a tree. Then, she covered it with leaves. Looking relieved that she was able to offer a better final resting place to the squirrel, we began to talk.

Your art resists simple categorization as sculpture or installation, painting or drawing. Could you tell us a bit about how you came to make this sort of work?

Priscilla Aleman [PA]: After undergrad, I went back to Miami and started working as an archeological technician, helping during excavations and archiving, learning a whole methodology of collecting and looking at information. This experience showed me how to understand the environment through fragments. I borrowed that way of categorizing, collecting, seeing and reviewing. I’m drawn to the more personal so I took this scientific approach and applied it to objects related to me, from my family or friends. There’s care involved.

Another large interest of mine is the afterlife and I pull from Afro-Cuban cultures and practices like Santeria. The materials that make up relics have such a charge. I feel this same charge in natural materials such as a seashell or kauri shell, certain plants, or elements like water.

All these things come together in these experiences. I say experiences as opposed to installations because they're in flux, they're meant to be experienced as a journey. I intend for them to be moved through until you reach a central space where materials are orbiting a central deity or goddess figure.The human figure is always the anchor because I find it to be an innate symbol in understanding both being human and the divine.

How often do these experiences change? Do you add things? If you reinstall in a different space, do you reimagine the experience?

PA: The experience inevitably transforms because it’s in response to where it is. Even when I’m making an experience, it's constantly in the flow state. There's this brewing, or feeding. And then at some point it does land.

For example, one piece, Stillness is in the Eye of the Hurricane, started in Miami. She is a blue deity with white maps tattooed on her face and veiled with a blue hurricane tarp. She started in Miami and came up to New York. The piece is experienced differently in NY because the space is more intimate and there is a bench in front of the deity where you can sit and rest whereas in Miami the viewer just circumnavigated her. So, it’s always changing depending on the space and time.

I'm thinking about sports, and I know this seems like a bit of a jump, but in these games, there are two constants: the court and the rules. But there’s also chaos, uncertainty. Amidst this chaos and constraint, there are bodies moving and strategizing. That’s the feeling I’m trying to recreate for the viewer.

Do you find that you make different things when you're in New York versus when you're in Miami? How does place relate to what you make?

PA: Yes, it does change. I spend time finding the nooks that remind me of Miami and going there—like the plant district. I love walking down the sidewalk with all the palm trees. It feels like home.

But absolutely it changes. In Miami, I had a lot more light in the work and now I come back to New York and I want to make demons. Mostly because I keep seeing gargoyles on all the buildings. I definitely respond to my environment, the symbols and colors and sounds. But I also pull from the roots of what makes me feel alive, like the call of parrots, which I miss.

Could you tell me a little bit about your National Geographic collages or paintings?

PA: I make paintings out of National Geographic magazines where I tear and cut into them and just let colors and content emerge. There was this moment that happened where I put a chiquita banana sticker on one page and then lay down a basketball card of a player doing a layup and the figures lined up perfectly! The same bodies come up again and again, in sport and in working, whether tending to the field or the orchard. It’s just curious to me and I want to dig deeper into that. The whole point of those paintings is to notice, to see and attend to whatever emerges.

Why did you pick National Geographic as the magazine you work with?

PA: I've been collecting them since I was a kid. My grandfather would give them to me, and they’re one of those magazines that are everywhere. As a kid I would flip through and feed my eyes with color and texture, I just liked it. It turned me onto archeology and existed as a daydream place.

While at Columbia, I started seeing it from a whole different perspective, learning about the colonial and exoticizing motifs in the magazines. But I still find them beautiful magazines, even if they have dirty baggage.

I like that when I'm looking through it and tearing or veiling something there’s a metabolizing that happens where I create a dream space that allows things to float and create new meaning. Maybe that’s part of me healing that history or allowing space for something new to germinate.

How do you collect the objects that you use in your work?

PA: Through going out into the world in different ways. Everything from accessing different archives or botanical centers like Montgomery Botanical Center, where they have a whole system of organizing plants as a seed bank, to visiting garage sales and seeing things in my parents’ house whenever I visit. Sometimes things are given to me by my grandparents. Like tree snails or other things that I wouldn't immediately think to collect. That plants a seed in my mind and every time I collect them, I think about whoever first gave me the object. Maybe I'm not seeing that person but it creates this connecting current.

It brings me a lot of joy to collect because it creates this experience of presence or stillness. There's something very tactile about kneeling to the ground and going through the Earth and finding these little snails and cleaning them. And as I’m holding them in my hands, they make this little sound like a chime.

Lastly, the objects come from making, for example my Grandfather gave me a papaya he grew and I made a mother mold of it so that I can make replicas in ceramic.

When you're collecting things, do you have a piece in mind or do the objects end up dictating the pieces that you make?

PA: Yes and no. What I mean is, yes, there is a piece in mind, in fact, there's usually like five pieces in mind. I kind of work like a chef with a bunch of things cooking at the same time, figuring out the recipes for them, and things start to cross over.

The central figure is always the thing I have in mind. For example, what do I want to collect for this figure that's in a dream space or what do I want to collect for this one that's a hurricane? But once it all arrives in the space or the studio, that's where things start to orient or I see narratives begin to emerge. It’s like playing a chess game—now I see the game plan, I see the board. It's a feeling. If I use my head too much, it doesn't happen, the piece becomes too stagnant.

The plaster figures—I’m thinking for example about the Wave Hill installation—are the casts taken from your body?

PA: Yeah, normally the sculptures are my body, but also my partners or my grandmother or friends. It's such an intimate process. Whoever I make a mold or cast of is someone that I know or feel very comfortable with.

It started as this sculpture practice that I did since high school, my mom casting my body. She's a nurse, so she knew how to plaster for mending bones. It was very intuitive for her.

In some way, it's also about trying to see oneself in an elevated way or in a higher state. Shrines are a way, I think, of trying to manifest what you want to be or what you want to remember. So, it's interesting to take my body and put it up there because in this way I can see myself from the outside, from a new perspective.

Do you think your work is in dialogue with our current climate crisis? And if so, how?

PA: Yes and no. In some ways I don’t think I’m trying to fight climate change. Instead, I want to acknowledge climate change and make work that connects me as a human back to the environment. Take water, or the ocean, for example. I want to remember that this element is not just the thing that we use to ship cargo but that there's a life force to it.

Gathering beauty through collecting—whether it be shells or seawater or sand—allows me to return to these places while I still can. I want to distill these feelings with the sculpture that I make. In some way, my work is caught between two emotional poles: trying to embrace and trying to let go.

What version of the past do you feel your work is in dialogue with and what kind of future is it trying to imagine or construct?

PA: The version of the past I access is through my imagination and daydreams but also from stories my family and friends tell. These worlds are embedded in my DNA, but I haven't gone to visit. I access these places through fragments. So where does that leave me in the past? Maybe trying to revive it? I don't know.

Maybe, the answer is that I'm really trying to engage with the present by looking at the past and then daydreaming, which I guess is the future.

You were talking about the afterlife earlier. Do you see that as a certain form of the future?

PA: I understand the afterlife as another realm. It's not in the future. There's just this divide. It’s not there, it's here somehow. And it can be accessed vicariously through materials or relics, whether it's a spoon or something in a museum. It just needs to be activated or looked at or seen in some way.

I guess the answer to your previous question is that in my logical brain of course I’m always thinking within the paradigm of past, present, future. But in the art, I’m trying to break down these divisions.

Image Carousel with 8 slides

A carousel is a rotating set of images. Use the previous and next buttons to change the displayed slide

-

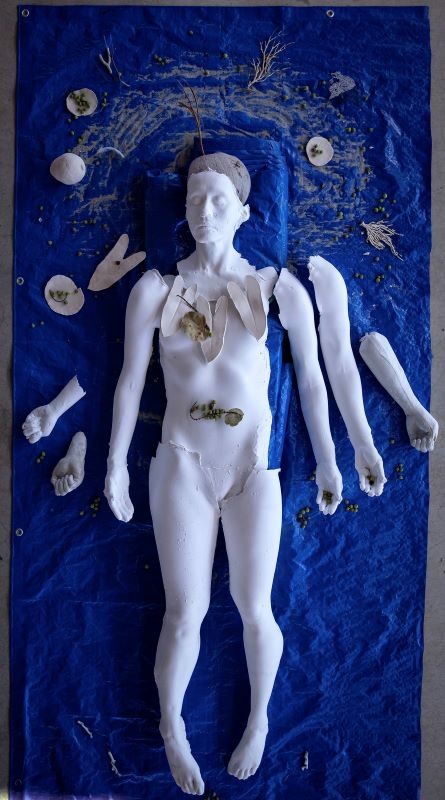

Slide 1: En Mis Sueños, 48"x 20'x 20', Plaster, Blue tarp, Collected sand from Key Biscayne, Coconuts, Snail shells, Ceramics, photography by Peter Vahan

-

Slide 2: En Mis Sueños, 48"x 20'x 20', Plaster, Blue tarp, Collected sand from Key Biscayne, Coconuts, Snail shells, Ceramics, photography by Peter Vahan

-

Slide 3: Origins of Devotions (Installation Detail), Dimensions Variable, Plaster, Blue Hurricane tarp as veil, Collected palm boots, Coconuts, Mamey seeds, Avocados from the Deering Estate, Tree snails collected by grandparents, Fragment of US-1, Palm tree leaves

-

Slide 4: Origins of Devotions (Installation Detail), Dimensions Variable, Plaster, Blue Hurricane tarp as veil, Collected palm boots, Coconuts, Mamey seeds, Avocados from the Deering Estate, Tree snails collected by grandparents, Fragment of US-1, Palm tree leaves

-

Slide 5: Origins of Devotions (Installation Detail), Dimensions Variable, Plaster, Blue Hurricane tarp as veil, Collected palm boots, Coconuts, Mamey seeds, Avocados from the Deering Estate, Tree snails collected by grandparents, Fragment of US-1, Palm tree leaves

-

Slide 6: 2021, Banana Boat, 11”x 7”x1”, Vintage National Geographic magazine, Resin, photography by Peter Vahan

-

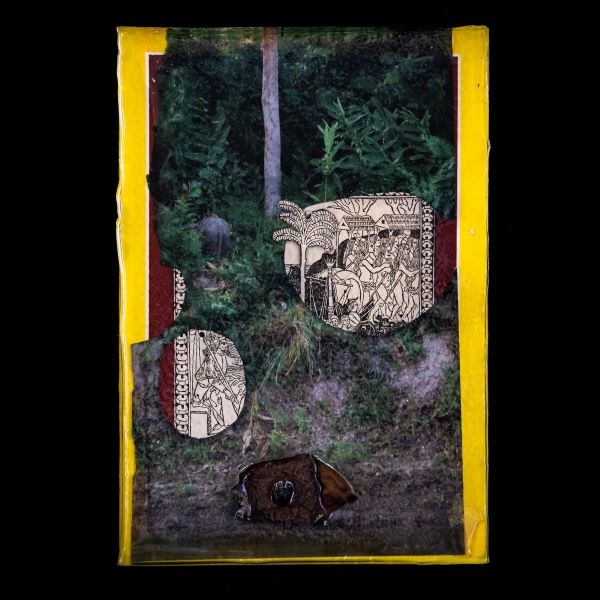

Slide 7: Where the Leaves May Fall, 11”x 7”x1”, Vintage National Geographic magazine, Resin, photography by Peter Vahan

-

Slide 8: Where the Leaves May Fall, 11”x 7”x1”, Vintage National Geographic magazine, Resin, photography by Peter Vahan

En Mis Sueños, 48"x 20'x 20', Plaster, Blue tarp, Collected sand from Key Biscayne, Coconuts, Snail shells, Ceramics, photography by Peter Vahan

En Mis Sueños, 48"x 20'x 20', Plaster, Blue tarp, Collected sand from Key Biscayne, Coconuts, Snail shells, Ceramics, photography by Peter Vahan

Origins of Devotions (Installation Detail), Dimensions Variable, Plaster, Blue Hurricane tarp as veil, Collected palm boots, Coconuts, Mamey seeds, Avocados from the Deering Estate, Tree snails collected by grandparents, Fragment of US-1, Palm tree leaves

Origins of Devotions (Installation Detail), Dimensions Variable, Plaster, Blue Hurricane tarp as veil, Collected palm boots, Coconuts, Mamey seeds, Avocados from the Deering Estate, Tree snails collected by grandparents, Fragment of US-1, Palm tree leaves

Origins of Devotions (Installation Detail), Dimensions Variable, Plaster, Blue Hurricane tarp as veil, Collected palm boots, Coconuts, Mamey seeds, Avocados from the Deering Estate, Tree snails collected by grandparents, Fragment of US-1, Palm tree leaves

2021, Banana Boat, 11”x 7”x1”, Vintage National Geographic magazine, Resin, photography by Peter Vahan

Where the Leaves May Fall, 11”x 7”x1”, Vintage National Geographic magazine, Resin, photography by Peter Vahan

Where the Leaves May Fall, 11”x 7”x1”, Vintage National Geographic magazine, Resin, photography by Peter Vahan