Who Narrates History? One Weekend Left to See 'Fictions of Emancipation' Curated by Professor Wendy Walters

Beyond the Metropolitan Museum’s Medieval hall, on the threshold of the Dutch masterpiece galleries, the bust of a woman rises above the foot traffic, her head framed in the archway.

She is a Black figure carved in white marble; her shoulders are bare, hunched forward, as though her arms were bound behind her. A rope crosses her chest, winds around her arms and under one breast. Her gaze is directed up and to her side, her brow furrowed, but her expression changes depending on where you stand.

The sculpture, Jean-Baptiste Carpeaux’s Why Born Enslaved! (22 ⅞ × 16 × 12 ½ " marble, modeled 1868, carved 1873) was created after the abolition of slavery in France and the Americas, and has been lauded for its sympathetic depiction of an enslaved woman.

But when Wendy S. Walters, Associate Professor of Writing and Director of Nonfiction, first encountered the bust in the Met’s European Sculpture Court, she wondered why—even post-abolition—the woman is still depicted as enslaved.

“People had many presumptions about Carpeaux’s humanistic intentions in making the work,” Walters explained, “even when there was no evidence to support that. As a writer, I found that paradox to be compelling.”

Why Born Enslaved! is now the centerpiece of Fictions of Emancipation: Carpeaux Recast, the exhibition Walters has co-curated to examine Western sculpture in relation to legacies of colonialism and transatlantic slavery. Featuring thirty-five works of art that offer depictions of enslavement and emancipation, the show opened in 2022 and will close on March 5, 2023.

Fictions of Emancipation demonstrates a bold, discursive approach to topics that are too often reduced to a footnote in other public cultural spaces. As major institutions tiptoe around equity and inclusion in their archives, Walters pulls racism out of the footnotes and margins and puts it under a microscope.

“I was invited to participate in the exhibition by Elyse Nelson, Assistant Curator for European Sculpture and Decorative Arts,” said Walters. “Our initial discussions had focused on the complexity of [Why Born Enslaved!] not just aesthetically—but also thematically.”

The show deftly unravels these themes into distinct strands for the viewer to grasp and follow.

Emancipation and anti-slavery imagery enjoyed an often self-congratulatory popularity in Europe in the late eighteenth and nineteenth centuries. Prints and porcelains, playing cards and seals—these delicate household objects show enslaved men, often on one knee, their wrists in shackles.

One such depiction on a Wedgwood medallion from 1787 reads ‘Am I Not A Man and a Brother?’ Nominally created in the spirit of celebrating abolition, they nonetheless reproduce images of enslavement for societal consumption—as Carpeaux himself did with Why Born Enslaved!

Images of the woman depicted in Carpeaux’s bust echo throughout the gallery, in Carpeaux’s clay studies for the sculpture, or across the work of other artists.

“This show is about sculpture, which carries its own qualities of aliveness,” Walters told me, “but the works are also representations, which gives them a feeling that is uncanny. More than portraits of individuals, these are works representing types of people.”

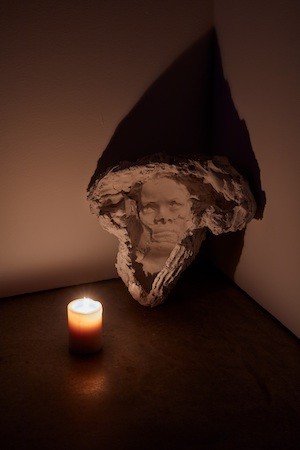

Kara Walker’s Negress (10 ¾ x 7 ¾ ", plaster, 2017) is an impression taken directly from the face of a reproduction of Why Born Enslaved! It occupies an otherwise empty enclave, in a corner on the floor, as intended by the artist. A representation in negative space, it suggests the hollowness of Carpeaux’s project, while still expressing the subjectivity of the woman frozen within.

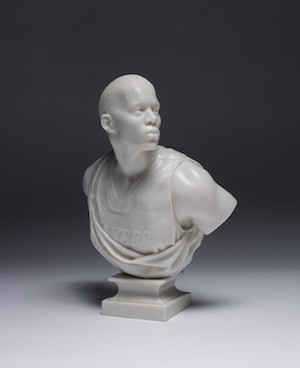

Nearby, Kehinde Wiley’s After La Negresse (10 ¾ x 7 ¾ x 5”, cast marble dust and resin, 2006) casts a basketball player in a Lakers jersey in the same pose as the woman in Why Born Enslaved!

“Wiley’s sculpture…was exacted in multiple miniature reproductions of the same, just as Carpeaux had done for Why Born Enslaved!” Walters noted. “These works are deeply entwined in their aesthetic, thematic, and financial histories.”

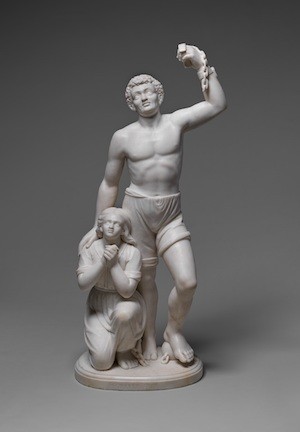

Across the gallery floor from Why Born Enslaved is a work by Carpeaux’s contemporary, the African American and Ojibwe sculptor Edmonia Lewis. One of the only professional Black artists working in the period, she poses a powerful disruption in the visual record dominated by white men.

Her sculpture Forever Free (41 ¾ x 22 ½ x 12 ⅜ ", marble, 1867) is a departure from virtually all other emancipation-themed depictions of the period: the emancipated Black man stands rather than kneeling or sitting; his foot is atop a ball and chain. He raises his arm high, lifting his broken shackles in his fist, while his other hand shelters the shoulder of the female figure who kneels at his side.

Forever Free is an early and significant work of Black self-representation, sculpted by Lewis two years after emancipation in the United States, and one year before Carpeaux finished his bust.

Proximity both in time, and in the gallery space, invites comparison between Forever Free and Why Born Enslaved! The show’s language directly poses these questions: “Who narrates history?” asks one placard, “What is Representation?” asks another; “What is Abolition?”

Just outside the gallery is a station where viewers can fill out cards in response to some of these questions and more—“How is this history relevant today?” “What does emancipation mean to you?” The display shelf was full of responses; long, short, ironic, and earnest.

“We understood early on that audiences would have a variety of responses to these works, but we also did not want to predict what those reactions might be,” Walters explained. “The response cards and spaces allow museum visitors to share their point of view…We have been collecting and cataloging those response cards all year to document the ways people have engaged with these incredible works.”

Inviting these responses is another way in which Fictions of Emancipation shows itself to be not only an aesthetically striking project, but one of extraordinary nuance. As a co-curator, Walters has assembled objects, images, and scholarship that trace the complexities of colonial and post-colonial narratives with an elegant, confronting lucidity. As an experience, it is as challenging and breathtaking as the figure given form in Why Born Enslaved!